China-India Brief #224

May 12, 2023 - May 23, 2023

Centre on Asia and Globalisation

Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy

Published Once a Month

Guest Column

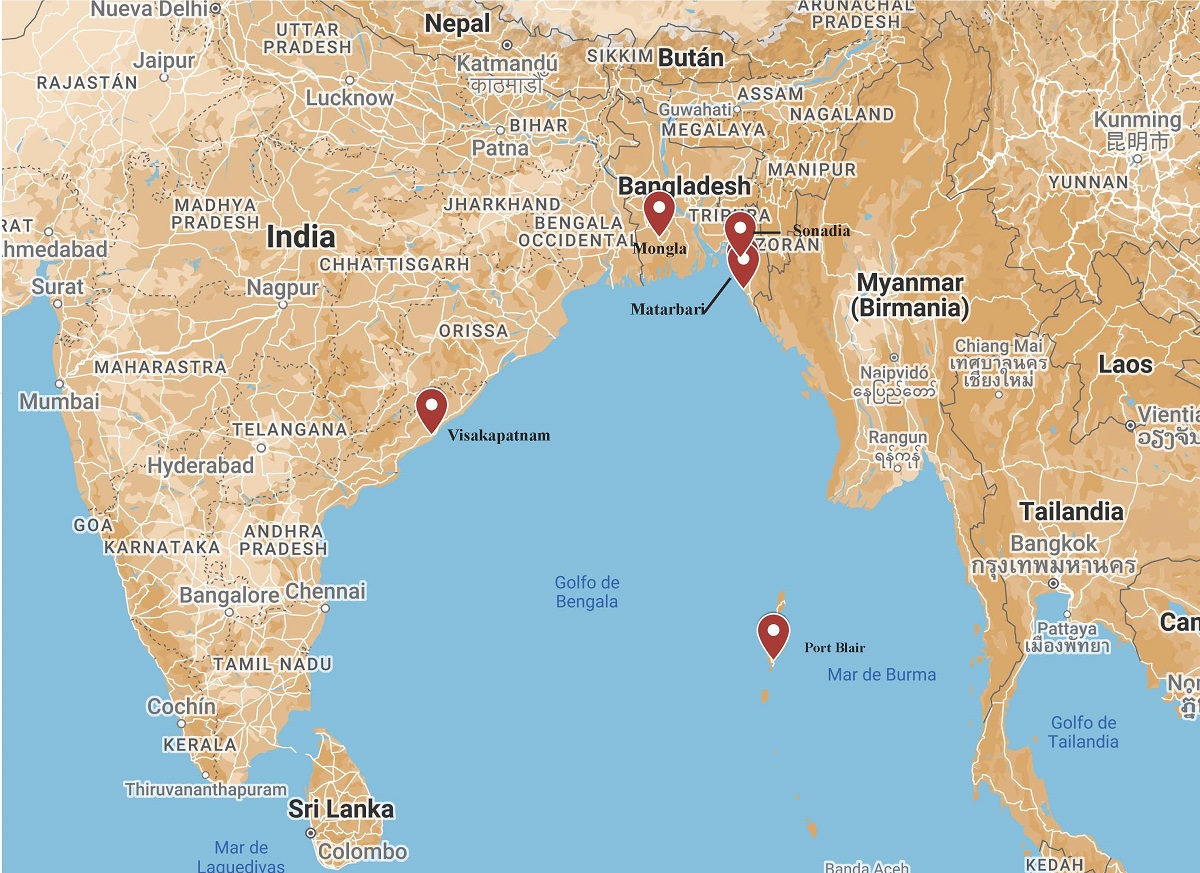

A basic Google search on the Matarbari port in Bangladesh will produce several articles that refer to the port as an India-Japan collaboration or as a ‘strategic victory’ for India and Japan against China. While the role of Japan in the development of the port is quite unambiguous, the role of India is not. The objective of the paper is to analyse the role of India and Japan in the Matarbari port development; what this port as an India-Japan collaboration means in light of the larger US-China great power rivalry in the Indo-Pacific region; and to understand the position of Bangladesh in this strategic environment.

Background

Matarbari port is a deep-sea port being built in the Moheshkhali subdistrict of Cox Bazaar district in Bangladesh. Located on the south-eastern coast of Bangladesh, south of Chattogram port (formerly known as Chittagong) it was initially being built to support the Matarbari coal plant. The Matarbari coal power plant was proposed in 2011 and has been under construction with generous funding from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) which first extended an Official Development Assistance (ODA) loan of 41 billion Yen for the coal power plant in 2014.

In 2018, the government of Bangladesh decided to turn the port into a deep-sea port, estimated to be completed by January 2027. JICA extended several loans for the development of both the Matarbari deep-sea port and the coal power plant. While the Chittagong Port Authority is also funding the project, Japan will be the majority investor. India is not making any direct financial investments in the port, which raises the question of India’s actual role. In order to understand the role of India and Japan in the project, it is important to understand the importance of the port for the different stakeholders.

Economic Importance of the Matarbari Port

Matarbari port’s importance for Bangladesh lies in the fact that it will be the country’s first deep-sea port. Bangladesh has had to rely on other deep-sea ports in the region, such as those at Colombo, Singapore and Malaysia, which greatly increases the transhipment cost for ships coming to/going from Bangladesh. As a deep-sea port, container ships with larger drafts will be able to dock directly instead of taking feeder ships to/from the bigger regional ports. In fact, Matarbari will be able to handle ships of deeper draft and larger cargo capacity than Chattogram port—currently the largest port in Bangladesh. The development of Matarbari port is expected to transform Bangladesh into a regional transhipment hub, increasing the country’s gross domestic product by 2-3 percent, and raising it to middle-income status.

Neighbouring landlocked countries like Nepal and Bhutan will also benefit immensely from the development of the deep-sea port, as it would reduce regional transhipment costs for their goods. India’s landlocked northeast region too will likely get an economic boost, with the improved connectivity to Dhaka.

Strategic Importance of the Matarbari Port

In order to understand the strategic importance of Matarbari port, it is crucial to know about an adjacent proposed port at Sonadia, located less than 50 km from Matarbari. Back in 2006, Sonadia was actually put forward as the most viable location for a deep-sea port. China was keen on developing the port and even submitted a detailed project proposal for the same. However, an agreement between Bangladesh and China never materialised. Instead, Dhaka announced in 2018 that the deep-sea port would be constructed at Matarbari with Japanese assistance. The final nail for Sonadia port came in 2020 when Bangladesh officially announced that it was scrapping the project.

Bangladesh cited environmental concerns and economic unviability as the reason for scrapping the project in Sonadia. Yet, though there is some truth to the view that Sonadia would cause environmental damage, the same can be said for Matarbari. A Greenpeace Japan report stated that the air pollution caused by the Matarbari coal power plant, of which the Matarbari port is a part, would significantly increase premature deaths in Bangladesh. This indicates that other factors were likely at play in deciding the fate of the Sonadia project.

Image Credit: Shahana Thankachan

Some experts like Anu Anwar believe that pressure from India played a major role in Bangladesh’s decision. And indeed, India has good reasons to pressure Bangladesh. If Sonadia port was developed by China, it would strengthen Chinese presence in the Bay of Bengal—deep in India’s sphere of influence. The distance from Sonadia to the headquarters of India’s Eastern Naval Command, located at Visakhapatnam, would be just 541 nautical miles (nm); and the distance to Kolkata, another important base for the Indian navy would be even less, at a distance of just 173 nm. Most significantly, a China-controlled port in Sonadia would put the Andaman and Nicobar Islands—what India sees as its natural aircraft carrier and one of its most important strategic assets in the Indian Ocean—dangerously close to the Chinese presence. Though China’s planned role in the Sonadia project was as a port developer, with Bangladesh retaining ownership, the example of Hambantota port in Sri Lanka demonstrated how such ownership could be lost to Beijing, and why New Delhi remains wary of China’s involvement in the region’s port development projects.

Matarbari port also serves an important purpose for India’s northeast region, comprising the ‘seven sister states.’ Mainland India’s only land connection with this region is through a narrow stretch of land called the Siliguri Corridor, or ‘Chicken’s Neck.’ China shares more land border with this region through Arunachal Pradesh than the rest of India does. India has several active border disputes with China in this region. Thus, while India’s northeast region holds great strategic importance, it is geographically isolated and has historically been one of the country’s most underdeveloped areas. The Japan-backed Matarbari port will provide another connection into the region for India. Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida during his visit to India in March 2023 talked about the development of a Bay of Bengal-Northeast India industrial value chain in cooperation with India and Bangladesh. This highlights the strategic importance of the port.

Great Power Rivalry in the Indo-Pacific Region

Matarbari Port’s significance also lies in the larger importance that Bangladesh as a country holds in ensuring a free and open Indo-Pacific. Japan and India are two of the key players in the narrative of the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific.’ Along with Australia and the United States, they are members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (or Quad). Increasing Chinese investment and naval presence in the Indo-Pacific region has been a great cause of concern for the Quad. Japan has a large stake in the trade that passes through the waters of the Indian Ocean and wants to prevent this region from following in the footsteps of the South China Sea. Japan and Bangladesh recently elevated their relationship to a strategic partnership. Japan is Bangladesh’s largest development aid partner, and the number of Japanese companies operating in Bangladesh has more than tripled in the last ten years. In the case of India, in addition to being a historical ally, Bangladesh is also considered a core part of its ‘Neighbourhood First’ policy and an important partner in its ‘Act East’ policy.

Double Hedging by Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s position in the US-led Indo-Pacific strategy has been ambiguous at best. Bangladesh has throughout its history adhered to a non-aligned principle in its foreign policy. However, On April 24, 2023, Bangladesh seemingly aligned itself with the US when it announced its own official “Indo-Pacific Outlook.” Along with the case of Matarbari port, it is very tempting to conclude that Bangladesh is shedding some of its strategic ambiguity and aligning closer to the Quad as a grouping. But the reality is more complex. A deeper look at Dhaka’s Indo-Pacific document reveals that Bangladesh has been very careful to not ruffle any feathers. The usage of the term “outlook” instead of “strategy” is a case in point. Moreover, one of its primary guiding principles is the foreign policy dictum of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman: ‘Friendship towards all, malice toward none.’ The tone of the document also highlights Bangladesh’s focus on economic cooperation rather than security.

Just looking at the outcome of Matarbari port on its own, it may indeed seem like some sort of ‘strategic loss’ for China. However, it must be remembered that China continues to enjoy immense influence in Bangladesh. China remains Bangladesh’s biggest trade partner and its largest source of imports. China also claims to be the biggest source of foreign direct investment (FDI) into Bangladesh amounting to USD 940 million for the 2022 fiscal year. Bangladesh joined the Belt and Road Initiative in 2016, and China has invested an estimated USD 9.7 billion in transportation projects in Bangladesh, some of which, are expected to have strategic implications. In addition, Bangladesh is also set to receive more than USD 40 billion in Chinese investments under the bilateral partnership.

Bangladesh is often cited as a close friend of India, but this relationship must also be contextualised in light of the domestic politics of both countries. While the current ruling party in Bangladesh—the Awami League (AL)—is considered close to India because of their historical ties, this is not necessarily the case with other political parties in the country, such as the Bangladesh National Party (BNP). Moreover, Bangladesh has seen several protests against the policies of India’s current ruling party—the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP)—for what it considers a discriminatory approach towards Indian minorities.

While it may be conceded that politically and culturally, Bangladesh is closer to India than to China, it is also a reality that India cannot compete with China in terms of the financial aid and investments it can provide to Bangladesh. In this respect, India has allowed close allies such as Japan to enter the picture to compensate for its own economic constraints. Japan is the only foreign country that India has ever allowed to invest in its northeast region and in the Andaman and Nicobar islands. Bangladesh, therefore, will continue to hedge with China and India simultaneously. It will prioritise its economic development while ensuring not to cross any Indian red lines.

The port in itself is undoubtedly a strategic victory for India and Japan, and for the Quad as a whole, but it is not enough to ascertain the position of Bangladesh in this equation. The competition for Bangladesh is a long game, and it is too soon to announce the winner.

Shahana Thankachan, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor at the University of Navarra, Spain. She tweets at @Shahana629.

The views expressed in the article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy or the National University of Singapore.

Image Credit: iStock/Md Maruf Hassan