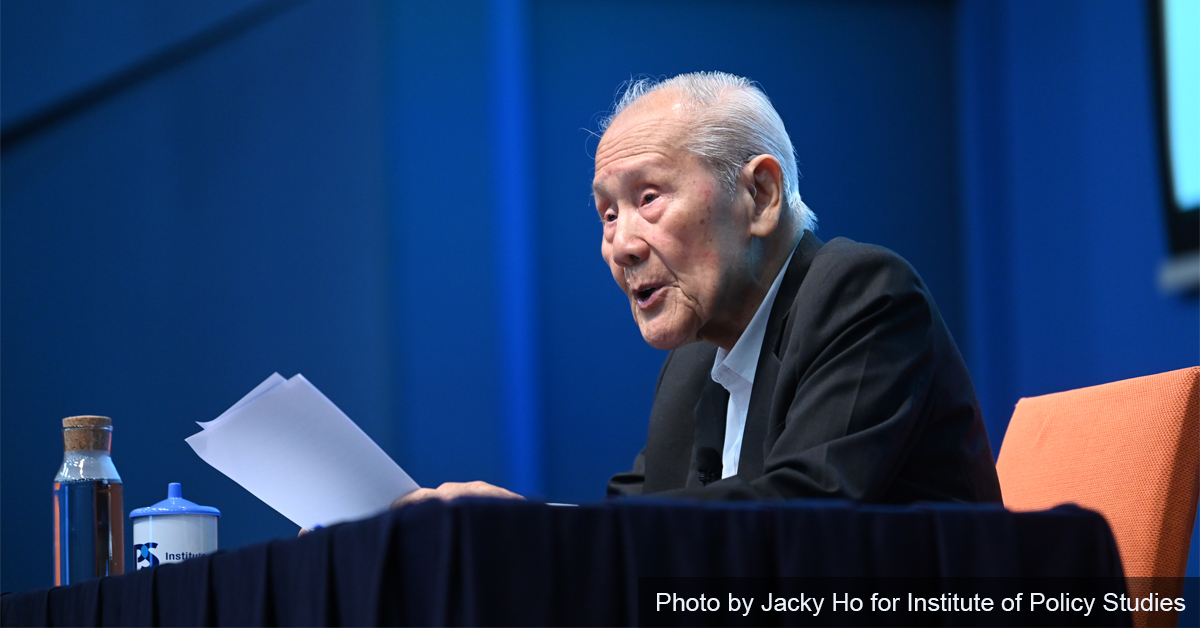

Following Professor Wang Gungwu’s first lecture on the impact of Indic, Sinic and Mediterranean ancient civilisations on Southeast Asia, the second lecture in his IPS-Nathan Lecture series focused on the region’s response to the eventual arrival of modern civilisation after European traders, militaries and colonisers entered the region.

Setting the context of the time, he noted that at the time that Portuguese and Spanish traders, missionaries and navy ships entered the region, the peninsular states were largely influenced by Indic civilisation with strong links to Theravada Buddhism, and they had established a trading environment within a localised framework. The archipelagic Nusantara states were largely Islamic, while Vietnam mainly retained the core ideas of the Sinic civilisation.

While popular scholarly opinion agrees that the arrival of the Portuguese and Spanish marked a turning point in the region’s history and possibly even the rise of modern civilisation across the world, Prof Wang asserted that this Iberian mission was not in itself modern. Rather, it marked the beginning of hostility between Catholicism and Islam in the region, just as there had been in the Mediterranean for centuries.

As Prof Wang put it, “What (the Iberian mission) signalled was the arrival of the Mediterranean heritage of the “civil wars” between two alternative paths of a common monotheistic faith.”

The Portuguese carried their hostility against Muslims to the region, and the Muslims in Asia retaliated, guided by Ottoman Turks in Istanbul.

As part of this struggle, the Portuguese conquered Malacca and the Maluku Spice Islands. In the meantime, Singapore was for a time the defensive frontier of the Malaccan forces, who were forced to give up their base up the Johor River and retreat to the Riau-Lingga archipelago. Thereafter, while trade continued in Portuguese Malacca, those in Singapore such as the Orang Laut were mainly aligned with Nusantara Islam.

Chinese commerce

Several significant shifts in Sinic civilisation were described, which affected early Chinese relations with the region. Military threats from the Mongol empire in the North forced the Ming dynasty’s rulers to concentrate on the continent, curtailing the exploratory efforts spearheaded by Admiral Zheng He in the Indian Ocean. As the rulers turned inward, coastal Chinese in the south relied on themselves to further maritime trade and interact with the Europeans who had made contact. In this period, Chinese merchants were prohibited from trading overseas, and trade was conducted instead through a highly controlled tributary system. Nevertheless, Chinese commercial influence grew. Local mandarins in the coastal provinces tended to relax this rule, allowing a booming private trade, including with the Buddhist states in Southeast Asia.

In the Sinic domain, the Portuguese were given administrative control of Macao in a unique arrangement that made it the only port city open to foreign private trade. Thus, the Portuguese did not have to operate through the tributary system, unlike their rivals. In the meantime, Hokkien Chinese had a significant presence in Luzon, northern Philippines, which gave the Spanish access to spices while bringing Chinese products across the Pacific Ocean via the Manila Galleon trade with Mexico.

As the four civilisations (Indic, Sinic, Islamic and Christian European) traded and competed on the same platforms in the region, Prof Wang concluded that the region’s confidence in their own cultures while adapting to the growing ambitions of these civilisations helped manage these complex relationships. They remained resilient because earlier civilisational influences had not been considered a threat to their cultures, but resources to draw on and enrich themselves.

Religious divisions and the advent of capitalism

As the birthplace of the Abrahamic religions, the Mediterranean has long been a site of conflict and competition, from the Crusades to the competing Muslim and Catholic influences over the Iberian Peninsula. This conflict between Catholic and Muslim forces also took shape in Southeast Asia, as Iberian missionaries generally failed to convert populations to Christianity when they had previously accepted Islam. Muslim populations generally met the Portuguese invaders with conflict, leading to disruptions in trading conditions and a more militarised Portuguese approach. The Portuguese thus lost their commercial advantages in the region.

As sea power expanded to the global scale, the English and Dutch East India Companies combined naval military and financial power, fundamentally changing the economic frameworks of their countries and the rest of the world with their control of long-distance trade. Religious proselytisation became secondary to profit-making. Prof Wang noted that this was the beginning of a more modern pursuit of wealth.

“It introduced the practice of state-protected private enterprise and may be seen as the young shoots of a new kind of political economy,” he explained.

“The calculations that propelled the Companies to pursue material wealth in this way could be described as the product of a modern mind, one that was not burdened by the traditions of church and state and concentrated on profitable outcomes.”

Historical records suggest it is unlikely that local elites and scholars in Southeast Asia were prepared for these radical changes and the growing world powers in Europe. Rather, given their modes of engagement with the other ancient civilisations, they were likely confident that their cultures were capable of accepting the Europeans. While the peninsular states remained largely preoccupied with conflicts among themselves, the Nusantara forces were more co-operative with the East India Companies initially, even striking up occasional alliances with the Christian European forces against each other as commercial interests took the fore.

This new modern civilisation overrode some of the civilisational differences that had previously endured in the region. Even in Europe, with the Enlightenment modern, the ideals of scientific rationality included new studies of the philosophies of Indic and Sinic civilisation. Modern civilisation approached the “uncivilised” frontiers in an unprecedented way — their mission was to bring progress without divine intervention, modernising ancient civilisations and eventually replacing them with a global civilisation.

This was exemplified by rivalries among European powers in Asia, where the French clashed with the English and Dutch. The intense conflict in the Indian Ocean during the 18th century resulted largely in a British victory. The Dutch East India Company was nationalised and the French were kept out of the archipelago, while Stamford Raffles was appointed the Lieutenant Governor in Java.

Question-and-Answer Session

Dr Norshahril Saat, Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, moderated a question-and-answer session with the audience.

Commenting on how history affected contemporary governance of Singapore, Prof Wang emphasised that as a colony, Singapore had always been modern, as the British introduced concepts of free trade and their administrative methods to the port-city. Previously, the people who had traded and lived on the island continued to be part of different ancient civilisations but, as part of the region, it also served as a place where various cultures and civilisations could meet. The British consciously separated people of different cultural origins in Singapore, exemplifying the colonial plural society. This reflects an attitude of modernity — making the best use of what resources are available without necessarily intervening in all aspects of life. The governing frameworks of modernity were inherited by Singapore’s independent government without much difficulty.

“That modern state was already there — (Singapore) just continued with it. And they continued to recognise that there were layers of civilisations in a plural society, which they acknowledged as being legitimate, equal and essential for the order and harmony that the new nation needed,” Prof Wang said.

Another question asked about the significance of technology in the dynamics of civilisations alongside ideologies and religions. Prof Wang noted that technology has always been key to competitions between peoples — for example, in ancient times, superior agricultural technology enabled civilisations to enhance their power. Such technology was made use of to increase production and improve people’s livelihoods. Prof Wang explained that this use and importance of technology is deeply rooted in the way civilisations and cultures grew. This was particularly true for Sinic civilisation, which had strong influence on our region especially in terms of skills and technology.

Click here to watch the video of lecture II.