Independent Australian think tank The Lowy Institute recently released the 2020 edition of its annual Asia Power Index. Measuring resources and influence to rank the relative power of states in Asia, this interactive digital tool was launched with a live discussion on 21 October 2020, featuring panelists Professor Joseph S. Nye, Harvard University Distinguished Service Professor, Emeritus and former Dean of the Harvard Kennedy School of Government; Senator Penny Wong, Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs and Leader of the Opposition in the Senate; Professor Khong Yuen Foong, Vice Dean (Research and Development) and Li Ka Shing Professor in Political Science at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, and Herve Lemahieu, Director of the Lowy Institute’s Asian Power and Diplomacy Program.

Clockwise from top left: Herve Lemahieu, Senator Penny Wong, Professor Khong Yuen Foong and Professor Joseph S. Nye during the launch of the Asia Power Index 2020 on 21 October 2020.

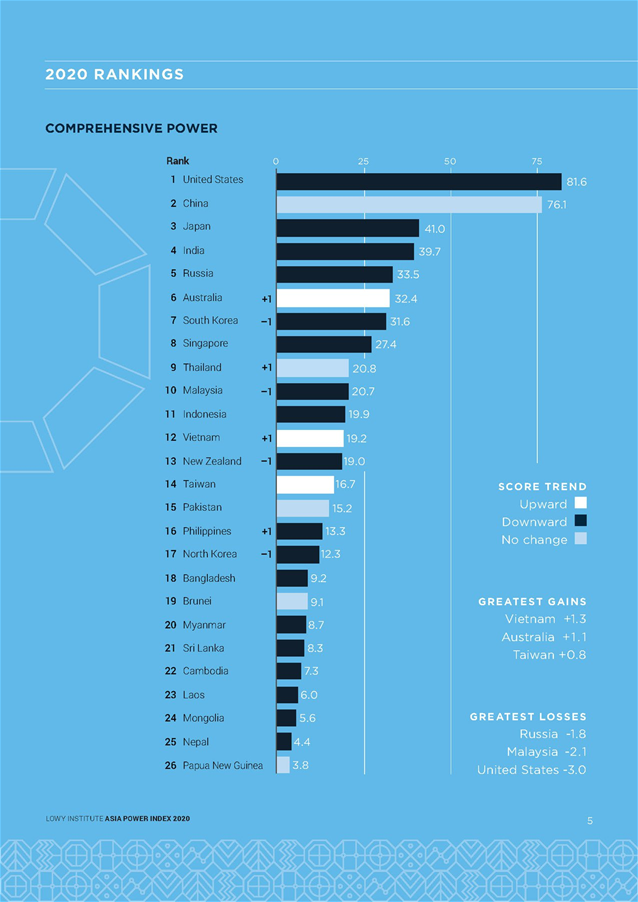

The index covers 3 years of data, 26 countries, and examines 128 indicators across eight measures: military capability and defence networks, economic capability and relationships, diplomatic and cultural influence, as well as resilience and future resources.

2020 Rankings: The Lowy Institute Asia Power Index 2020

2020 Rankings: The Lowy Institute Asia Power Index 2020

A bipolar region affected by the pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has created what Lemahieu calls “a bottom-heavy constellation of power in Asia”. 18 states in the Indo-pacific region have seen downturns in their relative power in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Overall, the United States, though still ranked number one in relative power, experienced a downward shift of 3 points, making it the greatest loss out of all 26 countries measured.

Professor Nye established that the pandemic had simply reinforced and accentuated existing trends. There had already been a downward trend in soft power and prestige for the US prior to COVID-19. Part of this could be attributed to the “America First” attitude that devalued multilateralism and alliances with other powers.

China, the other dominant power in the region, took second place and actually emerged relatively unchanged in its comprehensive national power. According to Professor Khong, China’s stagnant score could be attributed to its handling of the pandemic.

On one hand, China saw undeniable success in containing the virus and facilitating economic recovery. On the other, China’s delay in warning the world about the virus, its transactional approach to mask diplomacy and its wolf-warrior diplomacy balanced out its successes in the eyes of the rest of the world.

Indeed, the consensus across the panel was that the pandemic exacerbated and accentuated existing trends from prior to the pandemic. “It is useful to think of the pandemic as an augmenter and an accelerant of the disruptions that we are observing,“ said Senator Wong.

The evolution of the US-China relationship

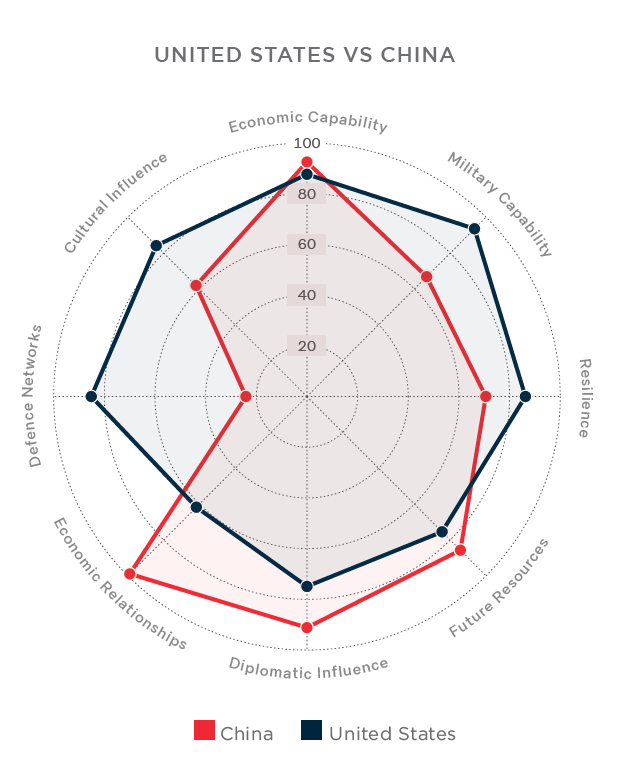

Even as the US continues to stay ahead of China in terms of comprehensive power, China is closing in. The report revealed that the United States’ 10 point lead over China 2 years ago has been narrowed by half in 2020. Furthermore, the US also lost ground in economic relationships and trade patterns in the region — areas where China was already ahead.

United States VS China across 8 measures: Lowy Institute Asia Power Index 2020

United States VS China across 8 measures: Lowy Institute Asia Power Index 2020

Whether or not this trend truly poses a threat to the US remains to be seen, but for Professor Nye, a reversal between the positions of US and China due to the pandemic is unlikely.

“The United States still has a number of power advantages that go beyond COVID-19,” he explained. Geographically speaking, China’s strained relationships and territorial disputes with some of its biggest neighbouring countries give the US an advantage over them in that regard. Furthermore, China’s dependency on oil imports still puts them behind the mostly energy-independent US, among several other examples.

According to Professor Khong, China’s position as a rising power explains its assertiveness across the decade. When the rising power reaches 80% or more of the established power’s strength, “the rising power will start to demand more things to reflect it’s growing clout.”

What is the endgame of this assertiveness? Citing the words of the late Lee Kuan Yew, Professor Khong suggests that China seeks a coequal relationship with the US.

But despite China’s wishes, coequality is also out of the question, as China’s failure to transform into a liberal democracy likely dissuades the US from granting it. As a result, it is likely that the stage is set for an “intense bipolar strategic rivalry”.

Despite the advantages that the US holds over China, the latter presents to the world an alternative model of development that also delivers results. In the eyes of many in Asia, where “performance legitimacy trumps political complexion in measuring prestige”, China may appear to be the superior power due to its successful handling of the pandemic and its aftershocks.

A cooperative rivalry

Ultimately, Professor Nye foresees a cooperative rivalry between the US and China. As the agenda of global politics trends towards ecological globalisation, which include efforts to combat the pandemic as well as climate change, it appears increasingly necessary for the US to work with China. To cite an example, it is impossible to combat climate change without working together with China, which is the greatest emitter of greenhouse gases.

Whether this cooperative rivalry can come to fruition depends on US foreign policies and attitudes, and this further hinges upon the results of the upcoming US presidential elections.

Regardless of the results, there will still be friction between the US and China. Speaking of America’s political situation, Professor Nye warns “There are people from both parties that believe that China tilted the playing ground in its favour with its aggressive nationalistic approach”.

However, a Biden Administration win in the 2020 election would lead to a change in tone from America’s current China containment policy. Biden, unlike Trump, would be more capable of handling a balancing act of both condemning China on certain issues and collaborating with them on others.

The role of the middle powers

According to the findings, three middle powers of the region — Vietnam, Australia and Taiwan — experienced increases in their standings.

This is indicative of how the future is likely to be defined by what Lemahieu calls “asymmetric multipolarity” — the region is caught in a situation where neither US or China can establish primacy, in which case the actions, choices and interests of the middle powers become more consequential.

Furthermore, in the event of a cooperative rivalry between the US and China, middle powers play an important role in keeping a sense of proportion and balance.

For Australia, their priority lies with finding areas of shared interests with like-minded middle powers in the region, and to not approach new groupings and engagements from a defensive mindset. “We need to think less about the binary of US-China competition, and more about what sort of region we want,” said Senator Wong. “We want to achieve balance in the region we want, on the terms we want.”

The View from Southeast Asia (SEA)

The rest of Southeast Asia continues to be pressured to choose between the two giants, but many of the SEA policy makers and leaders are reluctant to move from their current positions.

This does not mean that they are in a position of neutrality. According to Professor Khong, countries like Cambodia and Laos are more aligned with China than with the US, and in the last decade, several countries such as Malaysia and Brunei have inched away from the US and in China’s direction. Vietnam and Singapore, however, feel more strategic comfort with the US.

“The point to make about these movements is that they are not cast in stone,” said Professor Khong, “they remain fluid.”

But SEA nations will have to make a choice within the next decade, and will choose depending on their domestic policies, the actions of the two giants, their perception of economic opportunities, and their perceptions of American staying power.

To make a decision, SEA countries need to look at who has been “putting things on the menu”. China seems to be putting a lot of things on the platter, from the Belt-and-Road Initiative (BRI) to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). On the other end, US has the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) that was aborted by the Trump Administration, and has the upcoming Free And Open Indo-Pacific strategy.

“My fear is that one may just choose piecemeal,” said Professor Khong. “A series of piecemeal choices over time will put you in one camp or the other without you really intending it to be that way.”