The passing of Singapore’s

Platform Workers Bill is a

monumental step in addressing

the evolving nature of work in the

digital age.

As gig economy platforms such

as Gojek and Grab become

ingrained in everyday life, the

status of platform workers has

increasingly come under scrutiny.

Striking a careful balance

between protecting workers’

rights and preserving the

flexibility that the gig economy

aspires to provide is not easy. It is

an issue faced by many countries.

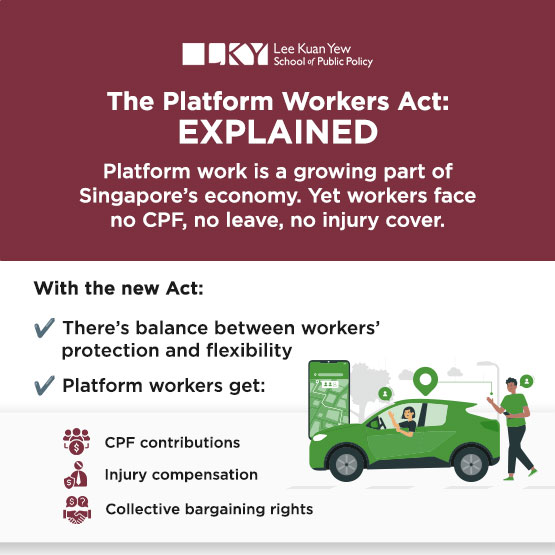

ADDRESSING THE

CLASSIFICATION DILEMMA

One of the thorniest issues in the

gig economy is the classification of

platform workers.

Currently, these workers are

classified as self-employed, meaning they lack access to the

benefits that employees enjoy

under Singapore’s Employment

Act. They do not receive paid

leave and Central Provident Fund

(CPF) contributions, and have no

mandated work injury

compensation.

Platform operators, on the other

hand, refer to these workers as

“partners” – independent

contractors who provide services

to consumers. This arrangement

theoretically gives workers the

freedom to work when and how

they want, setting their own hours

and determining their earnings

based on effort. However, the

reality is far more complex.

There is a clear power

imbalance between platform

workers and operators. Algorithms

dictate the terms of engagement,

and workers are heavily managed

by the platforms, from job

allocation to performance ratings.

The supposed autonomy that gig

workers have is often illusory.

To earn a decent wage, platform

workers must conform to the app’s

rules and work patterns, much like

traditional employees, but without

the associated benefits.

Singapore’s recognition of this

hybrid status in the new Act is a

crucial acknowledgment of the

reality these workers face.

A NEW CATEGORY OF WORKER

The Platform Workers Act carves

out a distinct category for

platform workers, acknowledging

that while they exhibit some traits

of employees, they also retain a

degree of flexibility.

The Act grants platform workers

protections that are much needed,

while still maintaining their

independent status.

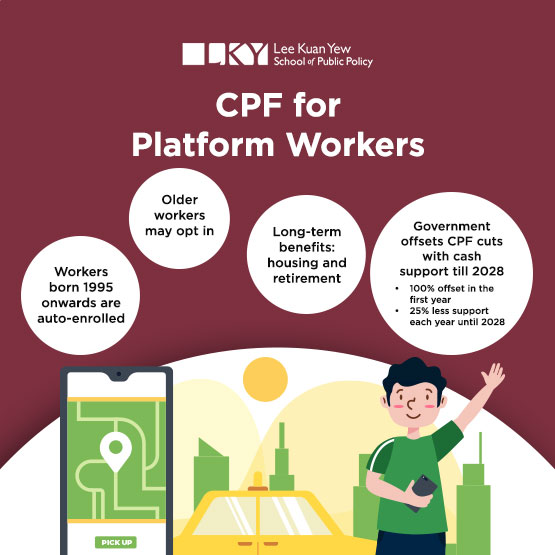

The most significant of these

protections are CPF contributions,

crucial for home ownership and

retirement planning in Singapore.

Platform workers born from 1995

onwards will be automatically

enrolled for CPF contributions,

while older workers can opt in.

While some may baulk at the

idea of lower take-home pay, the

long-term benefits of CPF savings

– such as easier access to housing

and retirement adequacy – cannot

be overstated.

Many platform workers

recognise the importance of

saving but need structured

mechanisms to help them do so.

The Act provides just that,

ensuring that CPF contributions

are promptly deducted and

funnelled into workers’ CPF

accounts.

Of course, there are concerns

that CPF deductions will hit

low-income workers the hardest,

with less cash to take home at the

end of the day.

But the Government’s decision

to offer support during the first

year is an important move,

softening the blow and ensuring

no immediate impact on

take-home pay.

Under the Platform Workers

CPF Transition Support scheme,

Singaporean platform workers

earning $3,000 or less in net

income from platform and other

jobs will receive direct cash

payouts.

These payments are designed to

offset the rising CPF contributions

to their Ordinary and Special

accounts as their contribution

rates gradually rise to match those

of regular employees.

In the first year, the increase will

be fully offset, with the support

reducing by 25 per cent each year

until 2028.

This phased approach, while

compassionate, is also strategic. It

gives workers the “nudge” they

need to invest in their long-term

financial well-being through

opting in to CPF deductions, a

decision they cannot later retract.

PROTECTING WORKERS WITHOUT

SACRIFICING FLEXIBILITY

Another essential protection

introduced by the Act is Work

Injury Compensation, which will

be on a par with what regular

employees in similar sectors

receive.

Delivery riders and private-hire

vehicle drivers face significant

risks in the course of their work. A

2022 Institute of Policy Studies

survey found that around a third

of delivery riders in Singapore had

experienced an injury requiring

medical treatment.

The Act recognises these

dangers and requires platform

operators to address workplace

risks through safety assessments

and risk control measures.

However, it is important to note

that this coverage extends only to

periods when platform workers

are actively engaged in work tasks

such as picking up or delivering

passengers or items.

While some argue that accidents

during waiting periods should be

covered, the unique status of

platform workers – who still retain

some control over their schedules

– makes it impractical to extend

full coverage for non-working

periods. This is a reasonable

compromise, ensuring protection

without overextending the

platform operator’s liability.

AVOIDING OVER-REGULATION AND

ACHIEVING POSITIVE OUTCOMES

While the Act is primarily

designed to safeguard the needs of

platform workers, it is mindful not

to overly burden platform

operators in the process. It offers

clarity on how liability is

determined for workers

performing tasks across multiple

platforms.

The administrative hassle of

determining the net earnings of

workers has also been reduced

through the application of a Fixed

Expense Deduction Amount

which computes a 60 per cent

deduction for those who use cars,

vans and lorries in their platform

work, 35 per cent deduction for

those who use motorbikes and 20

per cent for those who use

bicycles or public transport.

Some argue that the

Government should go further,

auditing algorithms for fairness or

guaranteeing minimum earnings.

However, as Senior Minister of

State for Manpower Koh Poh Koon

pointed out during the second

reading of the Bill in Parliament,

there is a risk of over-regulation,

which could stifle innovation and

harm the very workers the Bill

seeks to protect.

If companies are faced with an

unsustainable burden of

regulatory compliance, they may

opt to leave, reducing competition

and limiting opportunities for

workers. Singapore has wisely

chosen not to legislate in areas

that could disrupt the delicate

balance between worker

protection and business

innovation.

Instead, the Act empowers

platform worker associations to

negotiate collective agreements

with a platform operator and take

matters to the Ministry of

Manpower for conciliation.

Platform associations can thus

negotiate with operators on key

issues like compensation and

working conditions.

This approach allows for greater

flexibility and transparency, as

workers and operators can

collaborate to find solutions that

serve both sides’ interests.

Additionally, market forces help

restrain platform operators who

might attempt to pass on the

added costs of worker protections

to platform workers or consumers.

If platform workers feel they are

being underpaid or treated

unfairly, they can choose to switch

to competing platforms.

Price-conscious consumers are

also likely to opt for platforms that

absorb most of these protection

costs, even though they

understand they may face some

inevitable price increases when

using such services.

We must be realistic about how

much competition alone can push

platform operators to absorb

additional costs.

The nature of the platform

economy means that large players

dominate due to network effects,

drawing in more users and making

it tough for smaller competitors to

gain traction.

This is why regulation is

essential to curb anti-competitive

practices as the platform economy

continues to grow.

Without it, the market will

remain tilted in favour of one or

two giants, leaving little room for

true competition and therefore

less choice for workers and

consumers to vote with their feet.

THE TRIUMPH OF TRIPARTISM

The successful passage of

Singapore’s Platform Workers Bill,

while many other countries

remain stalled on this issue,

highlights the effectiveness of

tripartism in Singapore.

The close collaboration between

the Government and the tripartite

partners enables the Government

to simultaneously be pro-worker

and pro-business.

The Platform Workers Act – the

culmination of a three-year

process – is a testament to this

collaborative spirit, where multiple

stakeholders have been able to

come up with a well-calibrated

policy that protects workers

without stifling business.

This article was first published in The Straits Times on 18 September 2024.