What is the minimum amount of money a senior citizen requires to have a basic standard of living in Singapore? This is what a team of researchers, led by Assistant Professor Ng Kok Hoe of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, sought to find out in their recent study on Minimum Income Standards (MIS).

Speaking at the public launch of “What older people need in Singapore: A household budgets study” on 22 May 2019, Prof Ng shared that the team conducted focus group discussions with over 100 participants from a wide range of backgrounds, including individuals who lived in rental flats, to private property, minority groups and women. Participants came together to discuss how ordinary Singaporeans think about basic needs, and eventually came to a consensus on what an adequate household budget should be, in order to meet the needs of elderly households.

What constitutes a basic standard of living?

The idea of establishing MIS first came from the United Kingdom, where it sought to identify the amounts of income and list of things required for a minimal standard of living by society's standards. As the MIS approach has proven to be robust in the UK, and has been applied in diverse cultural settings from Portugal and Mexico, to South Africa and Japan, Prof Ng and his team adopted this method and adapted it to better suit Singapore’s particular socio-cultural context.

With focus group discussions, the MIS approach encourages participants to think about what a basic standard of living means - not just by their personal standards but by society's, a detailed list of items to fulfil this living standard, and the required budgets to obtain them.

Based on the conversations, the team devised a definition of the basic standard of living that captured the focus groups' sentiments:

The study particularly focused on four types of households with personas created for each of the following:

- Male, 65 years old or older, living alone;

- Female, 65 years old or older, living alone;

- Couple, 65 years old or older, living together;

- Male or female, 55-64 years old, living alone

Experts were also consulted to draw up meal plans for healthy and nutritious eating, as well as basic healthcare needs for persons in good health. Based on these and the profiles of the targeted types of households, a comprehensive list of items and services was generated, relating to housing and utilities, food, transport, healthcare, leisure, and cultural activities.

It also includes household goods that one would require in a two-room HDB apartment, personal care items and clothing. Items were priced based on direct market research at neighbourhood shops, chains like Daiso, hawker centres, as well as at online shops (Courts, NTUC and Ikea) - including only items that are easily accessible to most people. Items were also only included if all participants agreed that it qualified as a basic need.

According to the study, participants also felt that, “meeting the basic needs of older people involves considering their quality of life. Budgets should enable older adults to thrive rather than just stay alive.”

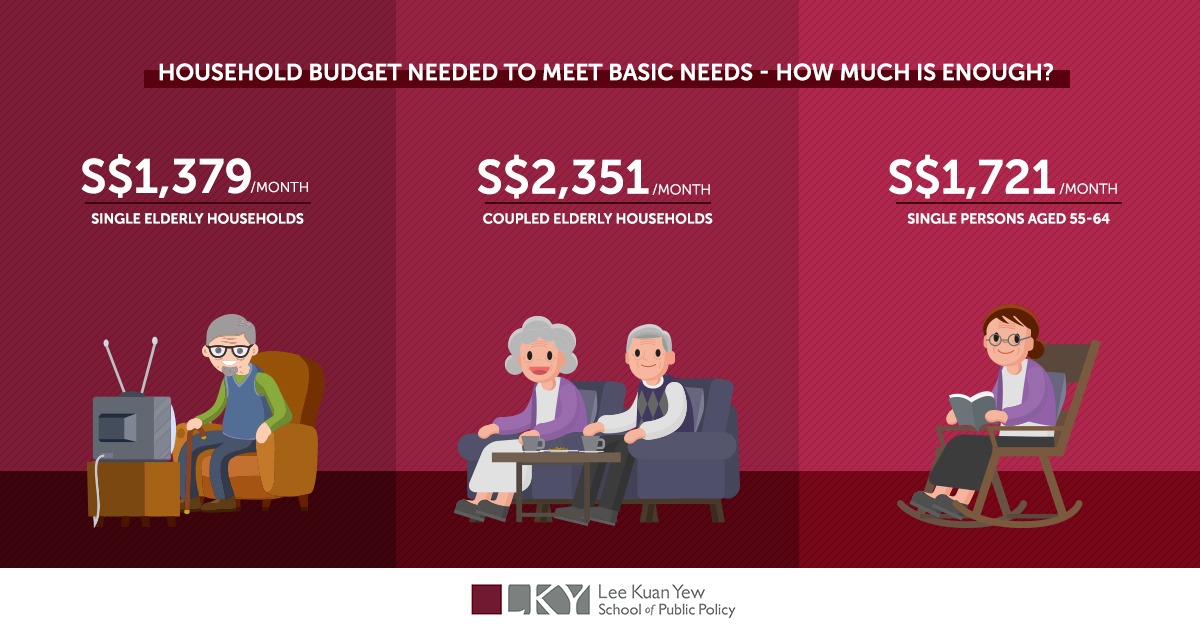

After coming to a conclusion on the list of basic needs, the minimum amount required to achieve a basic standard of living for elderly households was calculated as follows:

But, how does it all add up?

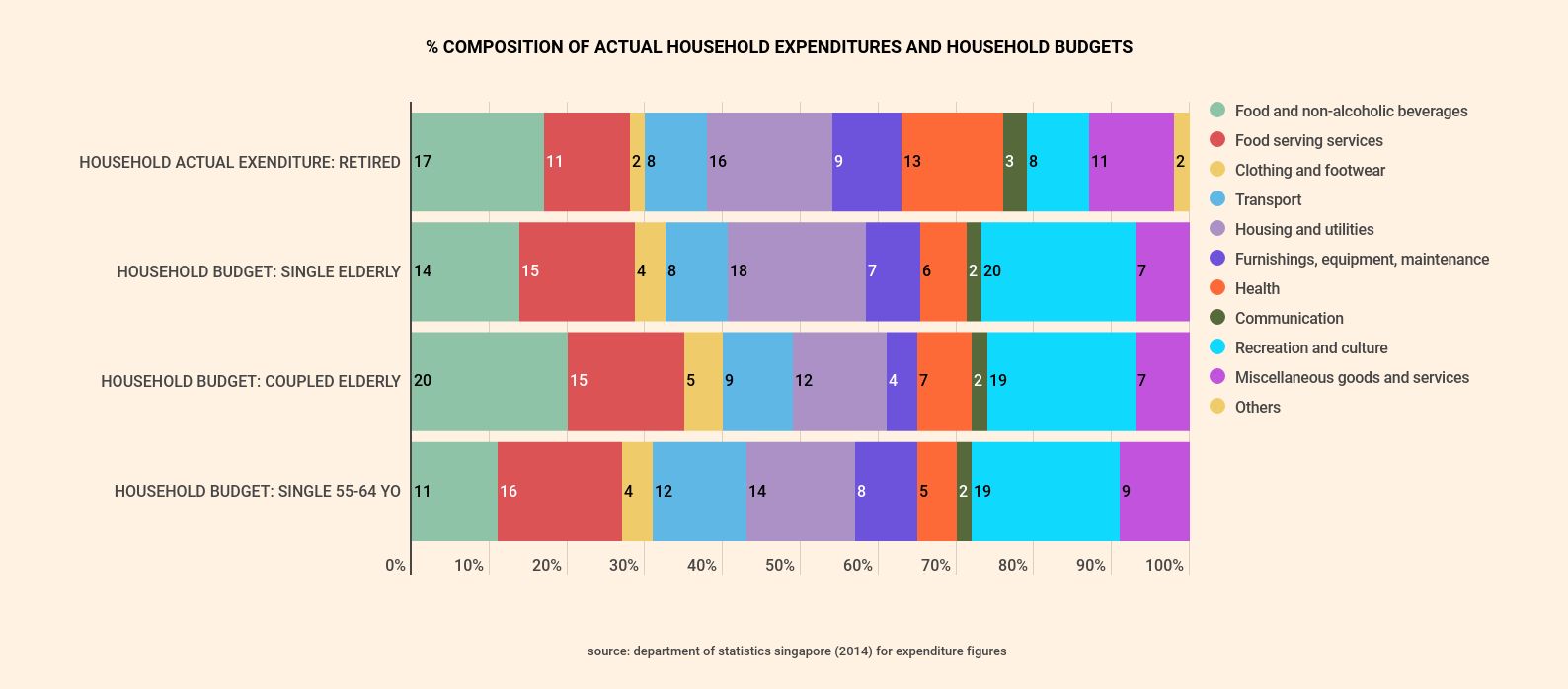

The largest share of the household budgets go to food (home-cooked meals, hawker food, and restaurant meals) for all household types, followed by housing-related items (housing, maintenance fees, and utilities). The third largest share of these households goes to recreation and cultural activities, which include holidays, leisure and religious activities.

"This study reveals that ordinary members of society can come to consensus about a basic standard of living in light of norms and experiences in contemporary Singapore,” said Prof Ng.

So, how many senior citizens in Singapore actually have access to this amount of money per month?

In Singapore, there is a heavy reliance on family support, with limited state support. Singapore’s Central Provident Fund (CPF) is a mandatory savings scheme that requires citizens to set aside a portion of their monthly income for post-retirement. This money can be used to purchase homes, and a portion can be withdrawn after the age of 55.

People who manage to achieve the CPF Basic Retirement Sum of $88,000 are entitled to a monthly payout of around SGD$790, far short of the budget for a single elderly person. Moreover, only around half of CPF members are able to hit this sum, as large portions of their savings go towards purchasing homes.

Adult children in Singapore have traditionally taken on the responsibility of caring for their elderly parents, especially if they live in the same household. But a declining birth rate means fewer children to take care of seniors. Standards of living have also changed such that many “sandwiched couples” are struggling to take care of both their own children, and their parents.

According to Ministry of Manpower, the median monthly work income of full-time workers aged 60 and above was SGD$2,000, which is approximately 1.5 times the budget of single elderly households. Older women however earn less, with the median earnings only about 1.3 times this budget.

Occupations matter too. Almost two-thirds of older workers are employed in the three lowest-paying sectors: cleaners, service staff, and plant and machine operators, and median monthly salaries range from 0.9 to 1.2 times the budget. For these people, retiring is not an option; living with just the bare necessities might even prove difficult.

How can we help the struggling elderly in Singapore?

With many elderly citizens working menial jobs well past their retirement age, some might argue that many of them prefer to do these jobs to keep fit and active, and that it helps to stave off dementia and loneliness. However, many simply have no choice but to work such jobs in order to survive. Lifelong learning is an uphill battle, especially for lower-skilled elderly workers. As certain jobs require long hours and offer very low pay, it is challenging for seniors to find the time to upgrade their skills.

There are currently schemes in place however, such as the ComCare Long Term Assistance Scheme, which sees beneficiaries receiving SGD$600 a month in financial aid and the Silver Support Scheme, which is a cash transfer for seniors in the bottom 20% of income earners. Senior citizens also enjoy benefits such as concessions on public transport fares, and significant medical subsidies. Still, some seniors continue to struggle to make ends meet because such schemes are often means-tested. Less than 1% of the elderly population receive ComCare Long Term Assistance.

Prof Ng cautioned, “Decision-makers should also be mindful that a fragmented state subsidy regime, and schemes that require individuals to put in applications, may impose help-seeking costs that could undermine efforts to support recipients in meeting their needs.

A number of charities and welfare organisations have stepped in to provide greater assistance to seniors, especially those living alone. Additionally, this year’s Budget saw a greater allocation of funds for financial assistance schemes for the elderly, such as the Workfare Income Supplement (WIS) scheme. This will provide lower-wage workers with increased wage top-ups, therefore helping them boost their retirement savings.

As for the MIS study, the research has already been used to support the Living Wage campaign in the UK, which encourages voluntary commitments from employers who can see both the ethical and business case for paying workers fairly.

That said, some concerns still remain. Rapid socioeconomic development, for example, means current older workers lose out to younger ones in terms of education and skills, which puts them at a disadvantage when it comes to work incomes. Some older workers might never have the means to retire, or will be permanently dependent on public and informal transfers.

Even for younger workers, lifetime wages can and will vary. With the increasing disparity in income equality in Singapore, people will become older with varying levels of savings, according to Prof Ng. And even as CPF participation and savings are projected to rise with the younger generation, the basic retirement payment of less than SGD$800 still only makes up about half of the budget required for a single elderly household; it falls significantly short of what is needed for a basic standard of living.

The MIS can serve as a benchmark for wages and other social interventions in Singapore. As Prof Ng explained, “Such income standards can help by translating societal values and real experiences into unambiguous and substantive benchmarks that policy can aim for. Future steps towards better income security should involve ordinary members of the public setting standards for decent living."

Learn more about the Minimum Income Standard and key study findings at https://whatsenoughsg.wordpress.com/

Photo credit: CJ Dayrit

If you’re interested in reading such content, subscribe here.