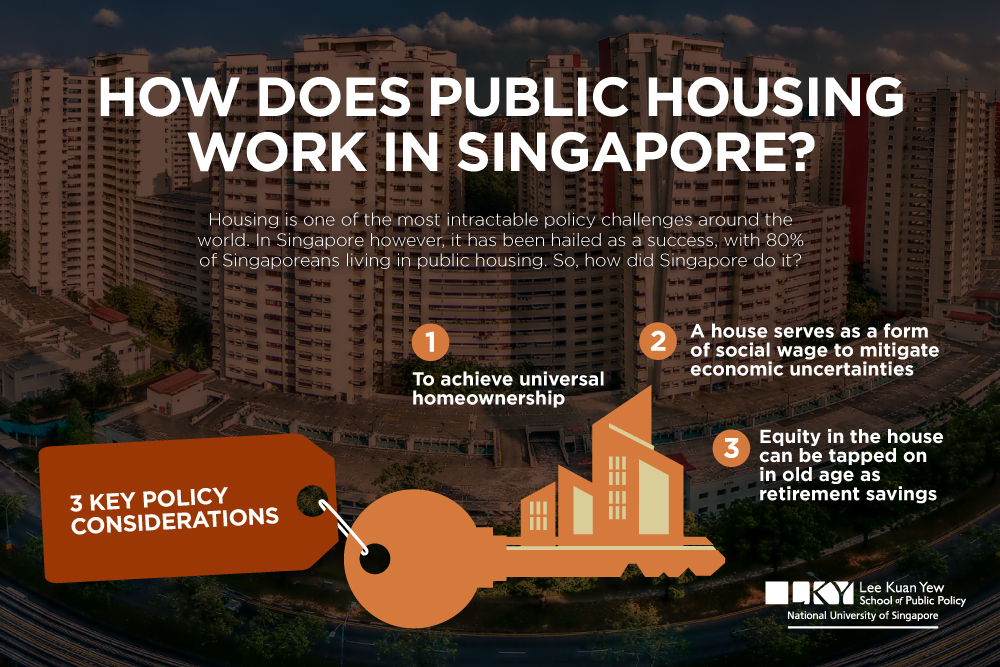

A whopping 80 per cent of Singaporeans live in public housing built by the country's Housing and Development Board (HDB). This sheer scale of public housing allows for it to be used to achieve a broad range of policy objectives, which are not always compatible with, or related to, housing.

In his recent research paper, Public Housing Policy in Singapore, Assistant Professor Ng Kok Hoe from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy asserts that as Singapore society evolves on both the social and economic fronts, public housing must change in tandem to remain relevant.

In his recent research paper, Public Housing Policy in Singapore, Assistant Professor Ng Kok Hoe from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy asserts that as Singapore society evolves on both the social and economic fronts, public housing must change in tandem to remain relevant.

He notes that in general, public housing policy in Singapore seeks to achieve two key pairs of objectives: the first is to ensure affordability and quality; the second is to build community and income security.

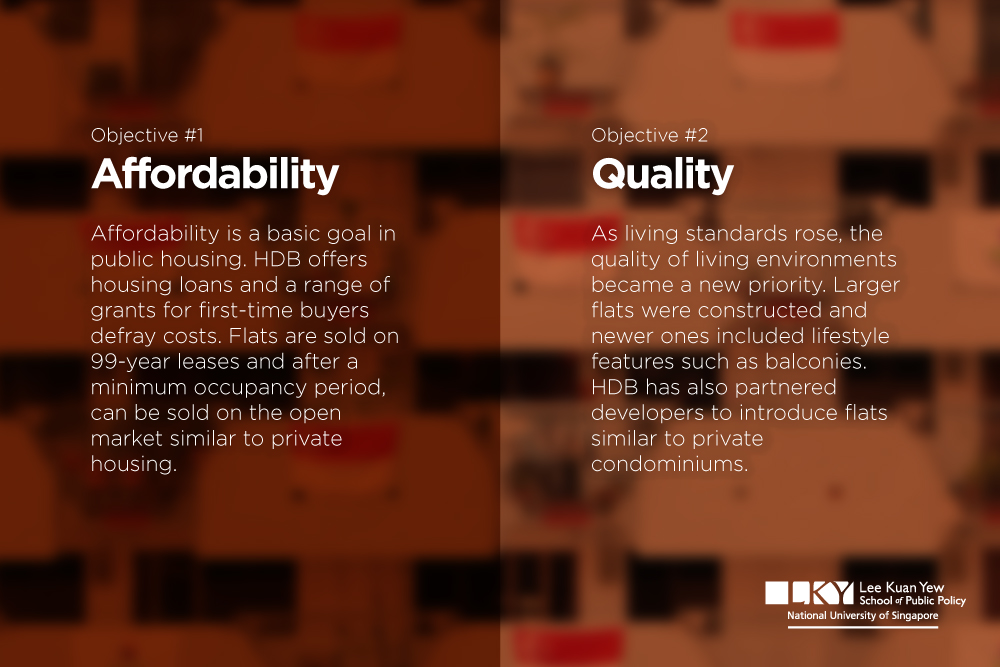

Affordability and quality

As with all public housing systems, affordability is a basic goal. The Government must be able to provide an adequate supply of housing, while ensuring people have the means to buy it. In Singapore, this is achieved through financial mechanisms built around the Central Provident Fund (CPF): Singaporeans contribute a percentage of their monthly earnings to their CPF accounts, and the Government sells bonds to the CPF Board to access these CPF savings, which are in turn used to finance public housing construction.

As with all public housing systems, affordability is a basic goal. The Government must be able to provide an adequate supply of housing, while ensuring people have the means to buy it. In Singapore, this is achieved through financial mechanisms built around the Central Provident Fund (CPF): Singaporeans contribute a percentage of their monthly earnings to their CPF accounts, and the Government sells bonds to the CPF Board to access these CPF savings, which are in turn used to finance public housing construction.

Flats are then sold to families through HDB, which issues housing loans that are eventually repaid through future CPF savings. First-time public housing buyers can also tap on a range of Government grants that help defray housing costs. After an initial minimum occupancy period, flats can be sold on the open market, and housing prices are then subject to market fluctuations.

As living standards in Singapore rose over the past few decades, the quality of physical living environments became a new priority for policymakers. Larger flat sizes were introduced, and newer flats included lifestyle features such as small balconies. New housing schemes reflected the public's aspirations towards owning private housing in select housing projects, HDB has partnered private developers to introduce a top-tier category of public housing that provides many of the same facilities as private condominiums.

However, affordability and quality do not always go hand-in-hand. Better-quality flats are more expensive, and public housing policy in Singapore is increasingly centred on providing greater diversity and choice. As a result, public housing is no longer uniformly affordable and accessible.

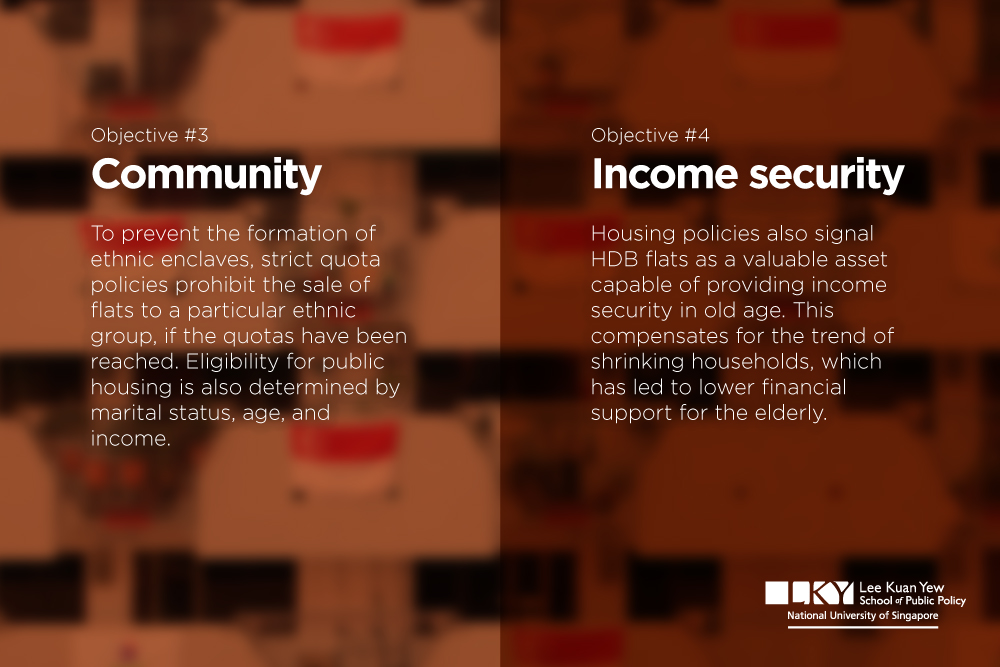

Community and income security

The vast scale of public housing in Singapore has allowed it to play a significant role in shaping the social dynamics of each neighbourhood, through both physical design and resident organisations.

The vast scale of public housing in Singapore has allowed it to play a significant role in shaping the social dynamics of each neighbourhood, through both physical design and resident organisations.

Design-wise, the ground floor of each block is left vacant, providing space for community activities and social interaction. Amenities such as playgrounds and sports facilities cater to the needs of various age groups. On the organisational front, resident committees organise an array of social activities. These groups come under precinct-level committees, which are in turn affiliated to community centres where residents have access to public services and other social programmes.

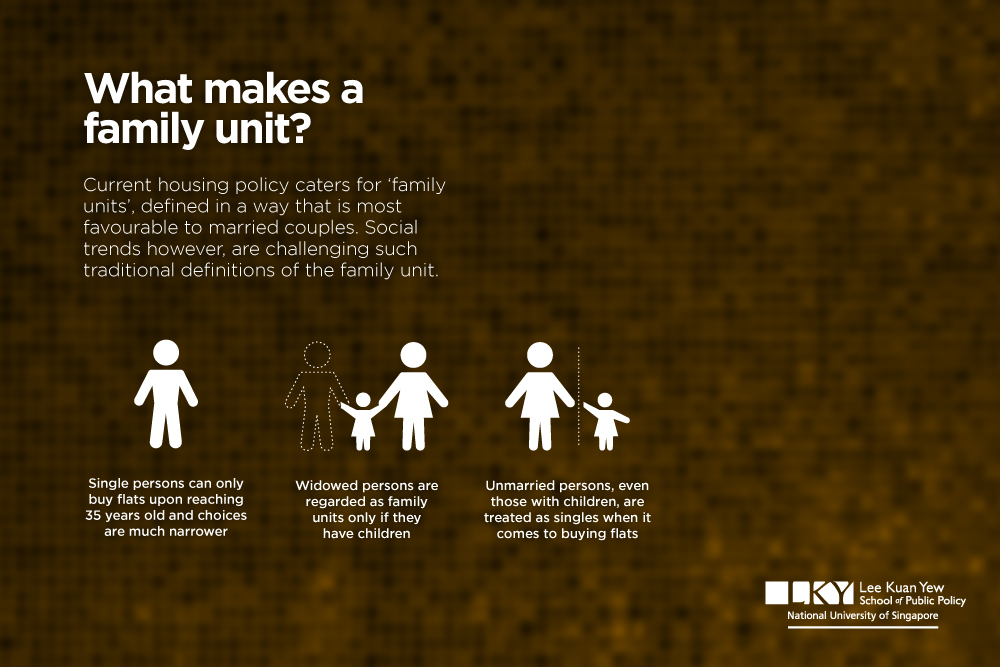

Policymakers have also taken care to prevent the formation of ethnic enclaves in neighbourhoods, through strict ethnic quotas which prohibit the sale of flats to buyers of a particular ethnic group if quotas have been reached. Eligibility for public housing is also determined by factors such as marital status, age, and income; in this way, housing policy attempts to encourage the formation of certain types of households, while discouraging others.

Separately, housing policy in Singapore attempts to communicate the message that public housing is a valuable asset that will provide income security in old age a message that has become increasingly significant in the wider context of an ageing population and smaller households in general. With these demographic changes, more elderly people in the future will not have financial support from working-age children, and will be encouraged to sell their flats and move into smaller ones. They will also be given the option to sublet unused rooms in their homes, or trade in the remaining leases on their flats to HDB in return for monthly payouts.

Separately, housing policy in Singapore attempts to communicate the message that public housing is a valuable asset that will provide income security in old age a message that has become increasingly significant in the wider context of an ageing population and smaller households in general. With these demographic changes, more elderly people in the future will not have financial support from working-age children, and will be encouraged to sell their flats and move into smaller ones. They will also be given the option to sublet unused rooms in their homes, or trade in the remaining leases on their flats to HDB in return for monthly payouts.

Challenges

The key challenges Singapore's public housing system faces are how to effectively cater to the needs of an increasingly diverse society, and respond to wide-ranging changes on both the social and economic fronts.

The key challenges Singapore's public housing system faces are how to effectively cater to the needs of an increasingly diverse society, and respond to wide-ranging changes on both the social and economic fronts.

As Singapore society becomes more diverse, the housing system must provide for households of different sizes, financial means, social needs and housing expectations.

Top-end public housing has greyed the distinction between public and private housing; yet, providing housing for Singapore's poorest families has become more difficult. Smaller flats dwindled in supply in the late 2000s, and as housing became more expensive, the only option available to such families were public rental flats, which were limited in supply. As a result, policymakers had to respond by building rental flats for the first time in years.

Top-end public housing has greyed the distinction between public and private housing; yet, providing housing for Singapore's poorest families has become more difficult. Smaller flats dwindled in supply in the late 2000s, and as housing became more expensive, the only option available to such families were public rental flats, which were limited in supply. As a result, policymakers had to respond by building rental flats for the first time in years.

Social trends such as a growing number of singles and single-parent families are also challenging the definition of the traditional family unit. Housing rules will have to evolve in tandem; politically, it will be difficult to continue treating such groups as exceptions.

Social trends such as a growing number of singles and single-parent families are also challenging the definition of the traditional family unit. Housing rules will have to evolve in tandem; politically, it will be difficult to continue treating such groups as exceptions.

Wide-ranging changes in the society and economy have also presented significant challenges to housing policy. Singapore's public housing sector matured during a period of rapid economic growth, where public housing became a tool for the redistribution of income across an individual's life stages, from working years to retirement. For this to work, the cost of public housing had to be kept low such that a vast majority of people could afford it. However, economic development simultaneously led to higher expectations of housing, befitting a more refined lifestyle. Housing policy became focused on upward housing mobility, rather than the provision of basic, affordable housing.

In recent years, the increasing ubiquity of flexible work and income insecurity during working age especially for lower-skilled workers has necessitated a closer look at the home ownership model based on buyers keeping up regular mortgage payments over a long period. In response, recent housing reforms have included smaller flats and shorter leases. These changes will not be the last.

In recent years, the increasing ubiquity of flexible work and income insecurity during working age especially for lower-skilled workers has necessitated a closer look at the home ownership model based on buyers keeping up regular mortgage payments over a long period. In response, recent housing reforms have included smaller flats and shorter leases. These changes will not be the last.

Changes on both the social and economic fronts will present a challenge to policymakers, who will need to expand housing options to meet diverse needs. In addition, demographic changes such as an aging population and changing family types will necessitate possibly dramatic shifts in housing policy. An increasingly uncertain labour market will also set the stage for Singapore's housing repayment model of the future. Such conditions mean continual innovation is key for housing policy to remain relevant and viable.

*To read more, see the full paper Public housing policy in Singapore.

*To read more, see the full paper Public housing policy in Singapore.