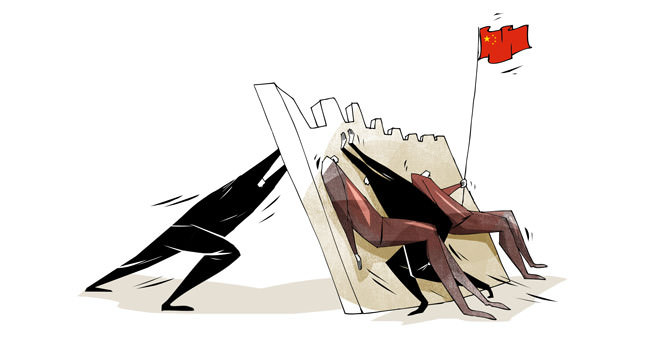

Recent commentary as the centennial of the First World War passed evoked two analogies: China now and Germany’s Kaiserreich in 1914; and globalisation then and now. While recent developments in the South China Sea and other regions where the Chinese have been more proactive may lead us to consider that China reflects the Kaiserreich in 1914, Prof Etel Solingen argues that such an analogy is “misguiding, and even dangerous.”

China appears to be a rising power with great aspirations to challenge the international political and economic order. It also seems to tighten the grips so as to have an ultimate control on its fate and shape East Asia according to her strategic interests. However, Prof Solingen argues that two factors constitute major differences between then and now: the dissimilar natures of domestic coalitions and a more interdependent international economic system. These should not misguide us in drawing analogies between historical and modern conditions.

China’s internationalising domestic coalitions

Prof Solingen highlighted that the main difference between the Kaiserreich in 1914 and modern China is whether the domestic coalitions are inward-looking or internationalising. Domestic coalitions and their interests are essential to how a domestic political and economic order might be established. The order itself, and its changes, has distributional implications for parties within and outside the coalition. At the same time, norms and principles of those coalitions determine the trajectories of a given country as they supposedly have the ultimate veto power during the decision-making process.

Today, the international economic system is more interdependent, and the costs of losing economic ties due to warmongering are very high. Perhaps more importantly, China relies heavily on trade that provides the currency for the survival of the Chinese regime. China is much more committed to the global economy and war averse than Germany was.

Prof Solingen cautioned that modern China is being governed by an internationalising coalition. Trade surpluses granted the currency and survival of the current Chinese regime that has been founded on a “well-off society”, at least since the 1980s. Although recent developments might reflect a rising level of nationalism in modern China, Prof Solingen does not believe the internationalising coalition in China needs to ride a protectionist and nationalist wave for its survival. She pointed out that, even if its defence expenditure is increasing, the military is still under the civilian control. While Chinese defence expenditure is between 6 to 16 percent, the Kaiserreich was spending 80 percent of appropriations.

Besides the decisive role of domestic coalitions, Prof Solingen also cautions that the international economic structure today is very much different from what the Kaiserreich faced a hundred years ago. The international economic system is more interdependent, and the costs of losing economic ties due to warmongering are very high. Perhaps more importantly, China relies heavily on trade that provides the currency for the survival of the Chinese regime. China is much more committed to the global economy and war averse than Germany was.

Based on such premises, Prof Solingen made the distinction between a coalition that is inward-looking or internationalising. The former implies that it is more likely to resort to protectionist trade policies and be more nationalist. This was the case in the Kaiserreich of 1914 where the domestic coalition was comprised of the military, agrarian, and industrial elites whose interests were constructed on protectionist, hyper-nationalist, and warmongering motives. The survival of the regime, according to Prof Solingen, depended on extracting legitimacy from a nationalist mobilisation. The civilians in the Kaiserreich did not have control on the military, which in return increased the likelihood of war in Europe in the 1910s.

Each era faces unique dynamics, and modern China is very much different from the Kaiserreich with respect to the nature and characteristics of the governing coalition. In her lecture, Prof Solingen draws out how these differences are complemented by dissimilar international order and dynamics, cautioning us how analogies should be drawn diligently by paying close attention to both domestic and international structures, and that the decisive role of nature and characteristics of domestic coalitions has certain implications on the likelihood of war in the world.

The currency for regime survival might change due to rising domestic consumption and declining exports. The author of this piece asked Prof Solingen during the Q&A session about the potential implications of a more inward-looking coalition then. Prof Solingen highlighted that China will not shift its course to autarky (self-sufficiency). Even if the economy depends more on domestic consumption, an internationalising coalition is not likely to lose its relative power as the main source of economic growth in the near future.

___________________________________________

On 7 October 2015, Professor Etel Solingen, Thomas T. and Elizabeth C. Tierney Chair in Peace Studies, University of California-Irvin, gave a talk entitled “Limits of Historical Analogy: Germany 1914-China 2015” based on her article “Domestic Coalitions, Internationalization, and War: Then and Now” published in International Security, Issue 39. For upcoming events by the LKY School, please visit our website.

Mehmet Kerem Coban is a PhD Candidate at the LKY School. His research interests are in International Political Economy, Political Economy, Financial Liberalisation and Financial Regulation, and Development Aid. His email is m.keremcoban@u.nus.edu