Geopolitical rivalry today has grown synonymous with zero-sum competition: "I win only if you lose"; "I thrive only if you are contained". Such development encourages sharp Manichean distinction between right and wrong, and good and evil. National security is made prominent and people grow conditioned to operate under an assumption of a permanent state of war or, at best, transient peace.

With national security accorded overwhelming importance, so-called economic statecraft emerges, according to which a nation's monetary, financial, and trade policies can be harnessed in the service of national security.

Unfortunately, such practice of economic statecraft has the potential to actually undermine the power and effectiveness of economic instruments. Economics is a discipline with two branches operating simultaneously: one, instructing agents how to advance their self-interests; two, clarifying how those agents, through their working to improve their own position, inadvertently promote everyone's well-being at the same time. Economics is about positive-sum games.

In specific cases of negative externalities or destabilising spillovers – or related challenges – economic policy should of course be more nuanced. But that does not imply desirability of the careless manipulation of economic instruments. Weaponising economic tools to intentionally disadvantage other nations in foreign policy (or industry competitors in domestic market competition) is a practice that, in almost all cases, self-harms.

Below we describe the kind of nuanced economic statecraft – and arenas for potential cohesion on the global stage – that can actually help both the international system overall and individual nations within it.

The end of the long arc of globalisation?

The decades of hyper-globalisation running up to 2015 might be viewed as halcyon days of yore. Rich countries traded goods with middle- and lower-income countries, extracting resources to fuel a manufacturing and industrial boom, and then latterly, exporting services and capital to these emerging economies. Faster transaction times afforded by the ICT revolution precipitated ever more rapid exchange of goods, services, people, ideas, and finance. Global inequality fell dramatically, with the populations of countries such as India and China lifted from extreme poverty.

But even if geopolitical rivalry had not disrupted this arc, other factors were already doing so.

Within advanced economies, the shift from manufacturing activity to services-oriented growth and employment – combined with import competition – made the maldistribution effects of trade ever more visible. Large segments of domestic populations grew increasingly disadvantaged, even as the sum aggregate of well-being rose on a global basis. The gains of populaces in China and India were seemingly set into contradistinction with the loss of economic security for many within advanced economies.

Added to that, the worsening global climate crisis has raised questions as to whether hyper-globalisation might run contrary to the green agenda. Moreover, the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic revealed fragmentation within many societies, and in the case of some countries, this fuelled the trope of ever-worsening economic inequality. And, in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the elevated commodity price environment has seeped into a cost of living crisis in many countries, where even rising wages have not been enough to cover the increase in the cost of basic human needs, including food, power generation, and transport. The return of industrial policy – and the conflation of economic, energy, and national security – has the potential to inject further doses of protectionism, thus complicating the landscape for companies, investors, and countries with cross-border interests.

In light of these challenges – and in considering the outlook for future cooperation in a post-pandemic world – the idea of universal global economic and trade cooperation should be appropriately modest. Even absent geopolitical rivalries, the same hyper-globalisation might no longer appeal to some advanced or emerging economies. But that does not mean cooperation and good competition are impossible. It simply inspires us to closely examine different problem domains.

Our suggestions for economic and trade cooperation

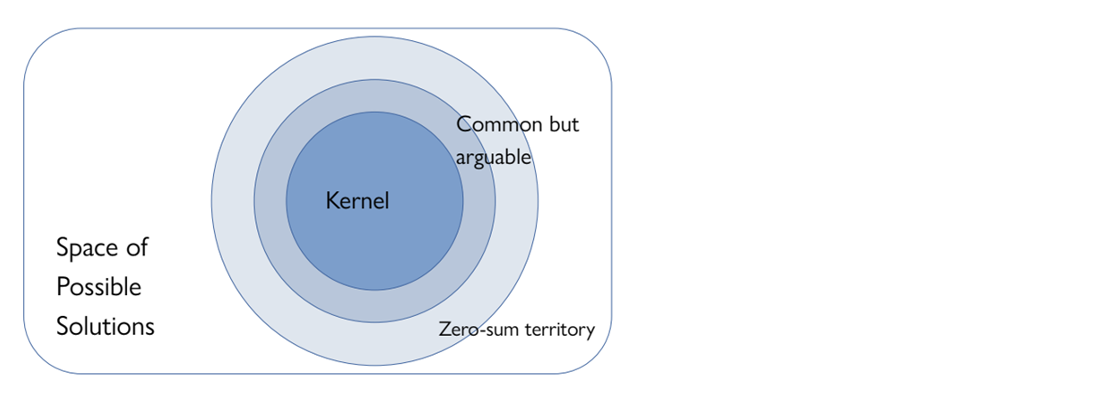

We propose dividing up the challenges of and potential for global economic and trade cooperation into concentric rings (Figure 1). In the innermost core are the common challenges that when properly addressed benefit all. In other words, cohesion and collaboration on such issues might mitigate negative externalities, which have spillover effects into other countries, regardless of the source. The effort to lessen the impacts of climate change – whether in the form of mitigation or adaptation – is certainly such a global issue, ripe for cohesion.

Figure 1. Working to order: concentric rings

Additionally, in considering macrofinancial linkages between countries, central banks, and financial institutions – and the potential for destabilising capital flows or bouts of financial instability to ripple across borders – continued coordination on monetary policy would help everyone across the global economy in the short and medium term. In addition, as the recent banking wobbles in the US laid bare, instability in one country’s financial institutions – even if domestically contained – can have a domino effect in other countries. Thus, synchronised supervision on behalf of regulators – with a view toward better managing the challenges of cross-border capital flows; banking; and identifying potential liquidity mismatches in non-bank financial institutions will also be important.

Moreover, strengthening global supply chains can provide the potential for positive externality, with spill-over benefits distributed to the entire length of the value chain. In the case of such scenarios, everyone has the potential to have their own interests aligned, and in their working together, also harbour the potential to yield benefits that are multiplied over and above those which result from single, isolated actions. Efforts here which are truly rooted in pragmatism – as opposed to those designed to exclude certain countries – are laudable.

The next outer layer we think of as challenges that are “Common but arguable”. The global climate crisis, interestingly, comes here in our taxonomy. While mitigating the impacts of global warming is universally beneficial, there are those nations – poorer, underdeveloped – who consider the price too large to pay or who disagree on urgency and scale of action. Side-payments, where the rich compensate the poor, will help, but these challenges will no longer be unambiguously universal, even if, as with the climate crisis, globally existential.

Growth-friendly fiscal policies with an eye to sustainability appear here, as different nations take different approaches to the challenges of going green – and might indeed learn from one another. Similarly, the race to establish a global minimum corporate tax will be calibrated within this second ring (ref Figure 1), as will be upskilling of the workforce in the face of varied technological trajectories, capacity bandwidths, and labour protections across nations.

This second circle ring may be most effective if it is underpinning by aligned interests – what Michael Oakeshott referred to as ‘enterprise association.’ In such a scenario, ‘like-minded’ countries engage with ‘unlike minded’ countries in the pursuit of shared goals and interests. Excluding “unlike-minded nations” will likely end up putting together too ineffectual a group. An example of such issue-based cooperation could be the Digital Economic Partnership Agreement (DEPA) which unites Singapore, South Korea, Chile, and New Zealand in an alliance on digital standards and advancing Digital New Deals.

Finally, the third, outermost ring records zero-sum territory in the domain of possible collaborations. That some large global players operate with confrontational mindsets renders interest-based cooperation in this space nearly impossible. The emerging technological decoupling between the United States and China – with its spillover effects across industries – is a case in point.

Our hope, however, is that the 80 per cent of humanity who live outside the Great Powers can work together, nonetheless, to reduce the size of this area, and – even in the midst of rivalries and tensions between the Great Powers – these Third Nations can drive the contents of rivalry ever further inwards towards those domains where collaboration is more likely.

This is a preprint draft of the article first published on the World Economic Forum (WEF), and so differs slightly from what was published on WEF.