Perhaps no country has adopted facial recognition technologies with as much vigour as China.

It’s not just used to unlock phones. Tech giants Alibaba and WeChat are rolling out ‘pay with your face’ technologies across China. Many cities are experimenting with face-scanning technologies on public transport.

Facial recognition systems in China have been deployed in multitude of areas in daily life, from both ticketing and publicly shaming jaywalkers, to limiting the amount of toilet paper people take in a public bathroom. And more ominously, China has been accused of using facial recognition technologies to suppress Muslim minorities in Xinjiang.

While many jurisdictions in Europe and the US have introduced significant limits on the technology, China has only started to develop principles guiding the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

But as the technology becomes more common in China, survey research shows that citizens and consumers there are equally, or possibly more concerned than people elsewhere about the privacy implications.

AI and facial recognition tech race

Facial recognition, coupled with artificial intelligence, is making major strides globally. But perhaps nowhere has it been as widely adopted as in China. The Chinese government has made no secret of its plans: it wants China to be the world’s AI leader by 2030.

The China AI development report from Tsinghua University found that China already generates more than a quarter of the world’s academic papers on AI, has become the largest owner of patents for AI and has the second largest talent pool after the US.

A looser regulatory environment, and a huge potential customer base in Chinese security agencies, would seem to benefit Chinese companies. Experts say there is a trade-off between privacy and potential commercial applications. It’s difficult to have both.

“If we want to maximise the application (or commercial) benefits, we have to sacrifice privacy, and vice versa,” says Assistant Professor Lee You Na of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

But commercial success in China might limit a company’s options overseas or force them to come up with a different version of their technology.

“In the Chinese context, it can give them an advantage. They, however, may be hampered in competing in a different context, for example, one with more stringent data segmentation policies,” says Dr Lee.

The different regulatory environments have already pushed some tech companies to offer different services in different places. One example is the Beijing-based ByteDance, which owns the social media app TikTok. It has started separating its Chinese and overseas operations.

But Chinese tech companies are also heavily dependent on US semiconductors. This became an issue earlier this year when the US government blacklisted Chinese tech companies over human rights concerns in Xinjiang province. In particular, the ban impacted image recognition software developer Megvii and security camera specialist Hikvision.

East VS West: Starkly different approaches

The issue of online privacy and facial recognition is a hotly debated one in the US and Europe. The European Union's General Data Protection Regulation bans the collection of facial recognition data that could be used to identify individuals. A number of cities in the US appear to be headed in a similar direction.

China, by contrast, is using facial recognition for national security purposes. And it looks set to expand those uses - from December 2019, the Chinese government will require anyone who wants a mobile phone contract to have their faces scanned to a government database.

But a structure for governing AI is beginning to emerge. Earlier this year, China issued a new framework for artificial intelligence research and applications, aimed at promoting the "safe, controllable and responsible use" of AI for the benefit of mankind.

Privacy concerns

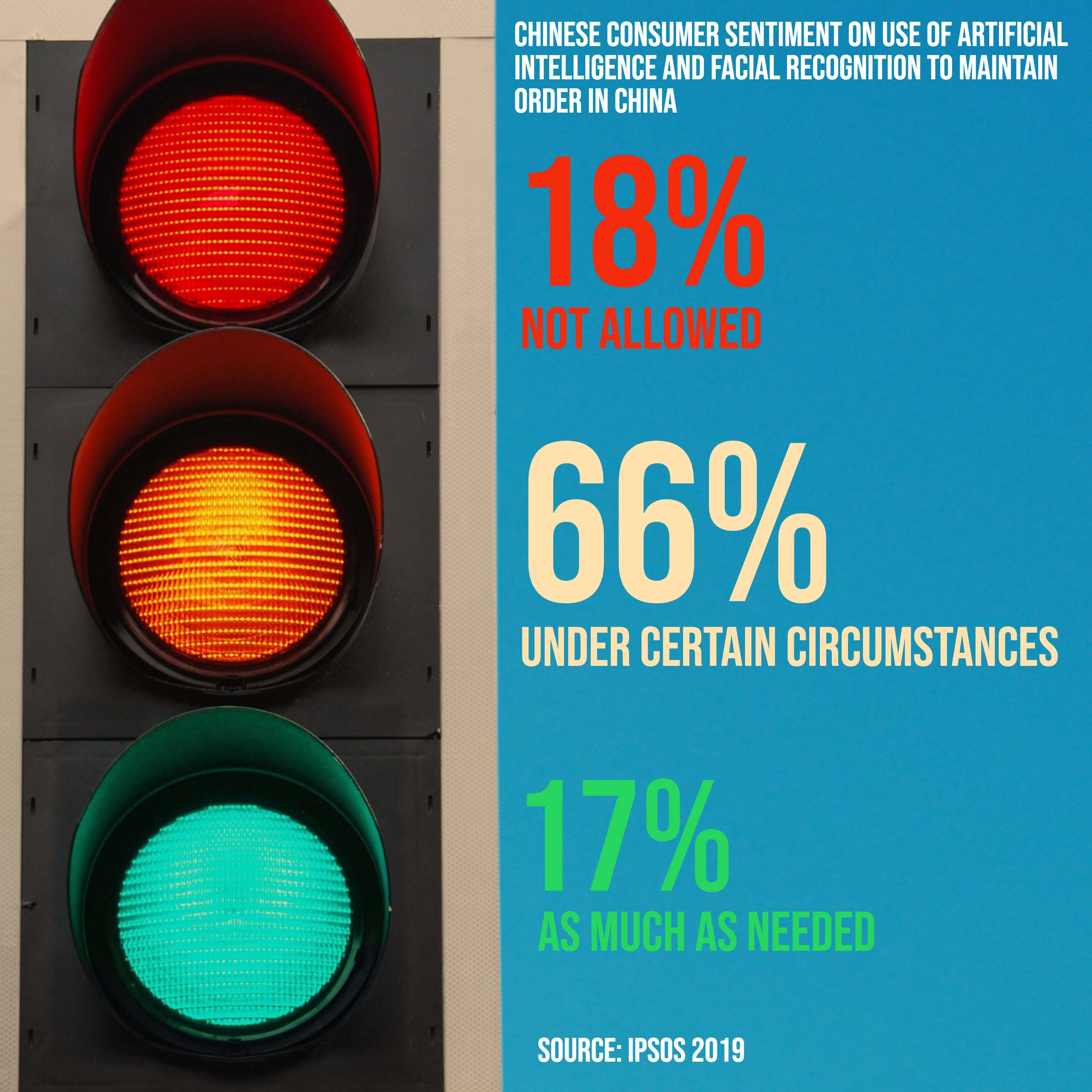

Even though many Chinese consumers appear happy to adopt facial recognition technologies, there’s evidence that they’re concerned about privacy. A global poll from Ipsos found that only 17% of Chinese respondents thought facial recognition “should be allowed as much as needed, even at the risk of citizens giving up their privacy,” making it one of the more privacy conscious countries.

A strong majority (66%) thought it should be allowed only under certain circumstances and subject to strict regulations. This is broadly in line with most of the countries surveyed.

A poll carried out by CCTV and Tencent Research found that 76.3% of respondents feel artificial intelligence posed a threat to their privacy. The AI application which they were most likely to be aware of was facial recognition. Similarly, research from Deloitte suggests that Chinese consumers are more sensitive than most about their personal data being used.

A survey of 3,088 respondents by Toutiao found that 53.15% of respondents support the “in-depth and comprehensive development” of AI. However, many respondents raised concerns about “AI losing control and causing social crises,” “AI making wrong decisions or judgments,” and “AI losing control and causing personal injuries."

Is privacy just an illusion?

The available surveys are a fairly vague summation of how people feel about the technology. While they collectively flag up some concerns, they don’t go into detail about which uses Chinese respondents find acceptable. The phrase “under certain circumstances and subject to strict regulations” in the Ipsos poll could mean a great number of things in practice.

Survey research in the UK and the US found that respondents were more likely to trust law enforcement with facial recognition data than private industry. According to Pew research, 56% of respondents trust law enforcement, while 36% trust tech companies and just 17% trust advertisers.

But Dr Lee says it’s a grey area, because it’s not always possible to easily separate government and commercial use of the data.

“The distinction falls apart if the government can demand access to the companies’ data. Also, companies may be able to get data which we think only the government should have. And, there is data that has always been public, but once it is widely accessible (and easily integrated with other public data), it can produce what feels like a novel invasion of privacy,” she says.

She also says western consumers shouldn’t feel too safe, because in practice, many policies give little more than the illusion of privacy.

Cookie policy in the EU, for example, mostly just forces users to click a button saying they accept the use of cookies. “Or, in the US, where companies are required to declare their privacy policies, if you actually read the policies (which almost nobody does) the policy declares, in effect, ‘you have no privacy’,” she adds.

Looking ahead

By some estimates, the global market for facial recognition technology will be worth nearly 10 billion dollars by 2024. As companies continue to develop the technology, they’ll need to consider both different attitudes and different regulatory environments.

Many tech companies might be surprised to learn that privacy appears to be a key value in most markets. Consumers in China, according to the research, appear more concerned about privacy than consumers in many other countries.

Similarly, many consumers in western countries might be surprised to learn that privacy protections are not always as robust as they seem.

(Photo credit: www.vpnsrus.com)