Asia is ageing at an unprecedented pace and the region is on track to have the oldest population in the world in the next few decades. According to the United Nations, a quarter of Asia’s population — about 1.3 billion people — will be over 60 by 2050. The larger proportion of senior citizens is the result of increased longevity and declining fertility. Living to a ripe old age can have its ups and downs, where for some, it might usher in the best years of their life, but for others, entering their ‘golden years’

can be stressful.

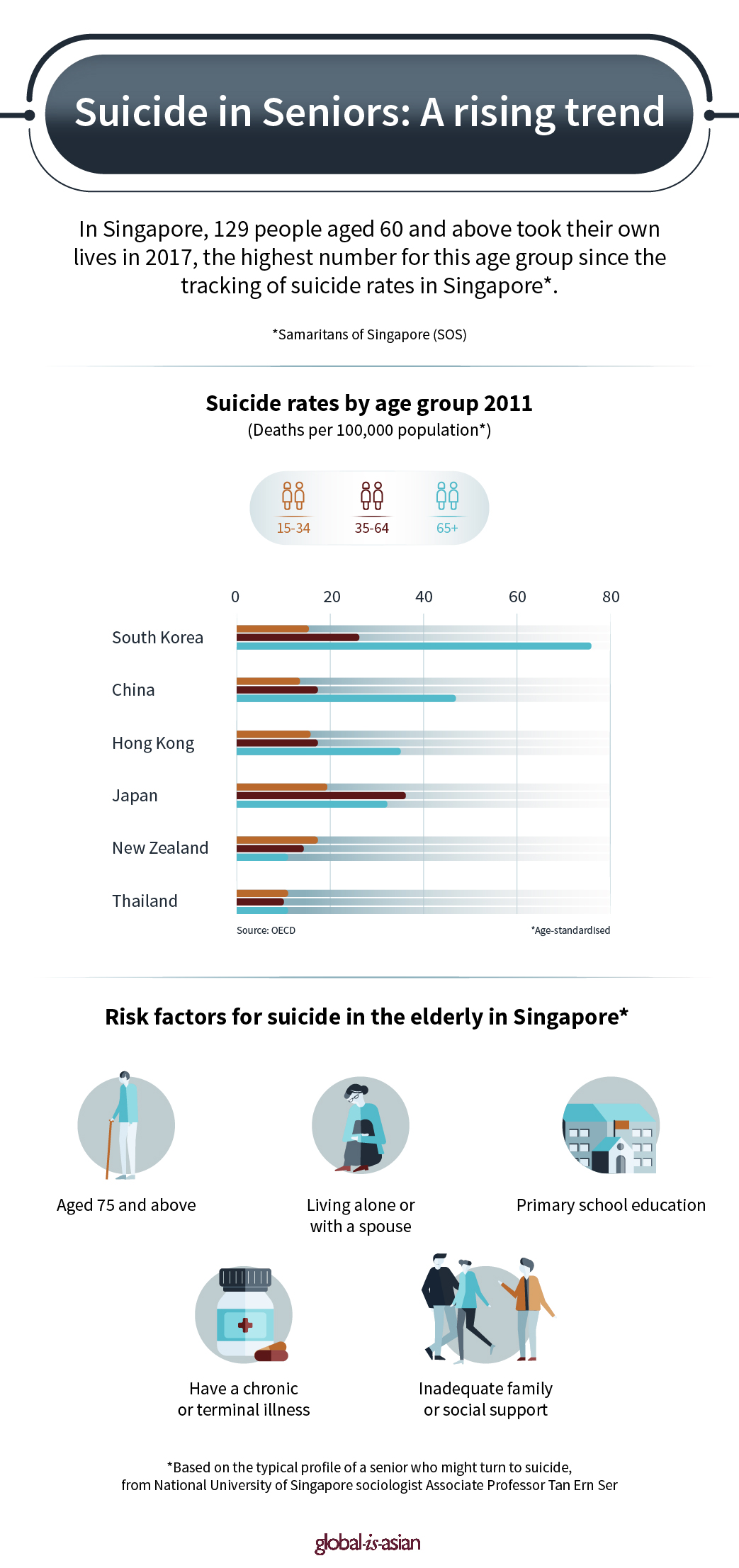

The process of ageing can create a unique stress amongst the elderly, with some turning to suicide. Singapore has witnessed a significant increase in the number of seniors taking their own lives over the past year. Government statistics provided by the suicide-prevention agency, Samaritans of Singapore (SOS), showed that 129 people aged 60 and above took their own lives in 2017. This is the highest number recorded for this age group since suicides first started being tracked in 1991. In comparison, the suicide figures for every other age group have fallen. This is consistent with global data showing suicide rates are highest among the elderly.

Loneliness, emptiness and hopelessness

Feelings of emptiness, loneliness and despair can lead to thoughts of suicide, especially if the elderly person believes that there is no other solution to life’s problems.

National University of Singapore sociologist

Associate Professor Tan Ern Ser says the typical profile of a senior who might turn to suicide is aged 75 or above, living alone or with a spouse, and who only has a primary school education. Dr Tan adds the most vulnerable group are seniors who have a chronic or terminal illness, particularly if they do not have adequate family or social support.

Other common struggles include the fear of burdening family and friends with their problems, and the daily difficulties they may face due to physical challenges, deteriorating mental health and financial issues. These worries can result in depression and suicidal thoughts amongst the elderly, especially when their struggles are not detected or addressed. Healthcare providers and researchers point out that many older people are uncomfortable talking to others about their feelings and they are far more likely to visit a doctor, rather than a social worker or counsellor.

Signs that a person might be depressed or contemplating suicide are all too often thought of as natural signs of ageing, making the lack of detection a major contributing factor to the high suicide rate in this age group. In this regard, physicians, social workers, counsellors and volunteers have an important role to play when dealing with those at risk, especially since suicidal attempts by the elderly are more often carried through than those by younger people. Dr Tan says this highlights the need for more training to help healthcare professionals recognise depression and identify those at risk of suicide.

Family and government support

Researchers believe that rapid economic development across Asia may be a contributing factor to higher suicide rates. In China, Korea and Japan the demographic patterns of suicides has changed. Today, rates are highest in rural areas for the youth and the elderly. Dr Tan explains that the migration of young people to the cities — where economic opportunities are greater — leaves the elderly behind without traditional social support and help from their children. Such migration in the pursuit of work and careers has forced some adult children to move far away, leaving them unable to offer immediate support and assistance to their elderly relatives when needed.

But the responsibility of caring for the elderly should not just fall on the family unit. Dr Tan says governments need to set up infrastructure too, such as a sustainable system of social security, healthcare insurance and housing for the elderly. Training for healthcare professionals is also crucial. Last year, Singapore’s government announced it would take a multi-pronged approach by working with community partners to raise awareness on suicide prevention, encouraging the elderly who are distressed to seek help, and providing professional support and crisis intervention to those at risk. Singapore’s Minister for Social and Family Development Tan Chuan-Jin said that "every death from suicide is one death too many, [so] we should endeavour to try and prevent it".

Can gatekeepers help?

Singapore is not the only country looking for a solution. Many Asian countries have tried to introduce so-called gatekeepers with suicide prevention skills. These are often community members who regularly come into contact with individuals or families in distress. These people include social workers, hotline volunteers, youth leaders, caregivers of those suffering from depression and religious leaders. According to the World Health Organisation, specialised training programmes have been implemented in Australia, China, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Korea, Sri Lanka and Vietnam, but their effectiveness is rarely assessed.

Dr Tan believes that seniors should prepare themselves “by staying healthy, active, employable and self-reliant for as long as possible”. They can also learn to be resilient, positive and sociable by developing good relationships with family, as well as strong social networks. To that end, there are now more activity-based, social, financial and educational programmes in Singapore to support the elderly. But Dr Tan stresses that all of these hinge on having a buoyant economy that could help fund the many support groups and programmes for seniors.

(Photo:

Gramicidin, cropped from original)