Recently, I attended a relative's wedding in Hong Kong. The turnout of my extended family was unprecedented—leaving China amidst the Chinese Civil War in the 1920s, members of my father's family had scattered across Asia, ending up not only in Hong Kong and Singapore, but also in the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia.

I was excited to meet distant relatives and learn more about their lives. Coming as we were from the same roots, it hadn't occurred to me to expect language barriers and differences in cultures.

Sitting at one of the tables in a crowded banquet hall, I tried conversing in Mandarin with one of my relatives from Fujian, China, but she responded in an unintelligible dialect; it sounded like the Hokkien (Min) dialect that we spoke at home, but distinctly different in enunciation. Conversations with my Filipino-Chinese relatives were slightly more successful, but it was clear that they preferred to communicate among themselves. I later learned from my uncle that while the older relatives still tend to converse in the dialect of our ancestral home, the younger generation have already grown accustomed to speaking the mother tongue of their adopted homelands, such as Tagalog or Cantonese.

Two generations into the diaspora, people who share the same ancestors now embrace a multitude of identities.

Effects of the Chinese diaspora in Singapore

My experience is not unique; Chinese communities across Southeast Asia can trace their roots to mainland China. The Chinese diaspora began in the late 19th century, and occurred throughout the early parts of the 20th century. While some migrants came to seek a better life, away from the poverty, famine and war in China, others arrived as indentured labourers. By 1957, there were approximately 1.4 million Chinese in Singapore.

But what is the Chinese diaspora? Professor Wang Gungwu, who studied the Chinese diaspora extensively, defines it as "those of Chinese descent who have made their homes and settled as nationals in a variety of countries, specifically in Southeast Asia. This would exclude overseas Chinese who still hold Chinese nationality.

Our forefathers brought their culture, traditions and languages with them. While the diasporic Chinese identity, or "Chineseness", varies from place to place and is ever changing, the majority of Chinese migrants maintained their Chinese identity for practical rather than sentimental reasons.

The diaspora was able to distinguish between cultural and political identity, and "Chineseness" did not necessarily entail identifying with the Chinese state. The Chinese recognised the importance of being loyal to the host country. However, they resisted complete assimilation as their Chinese identity helped to cultivate business links and other activities.

In an article entitled ""Among Non-Chinese", Professor Wang states that Chinese communities sustained their Chineseness by "using Chinese language in their day-to-day trading activities, by following birth, marriage and death practices, by celebrating festivals and professing certain religious practices. With time the Chinese built their own schools for their children and recruited teachers from China". A common identity also helped to strengthen business ties among the Chinese, especially in more traditional industries such as the selling of construction, commodities and furniture.

Is "Chineseness" dying out in Singapore?

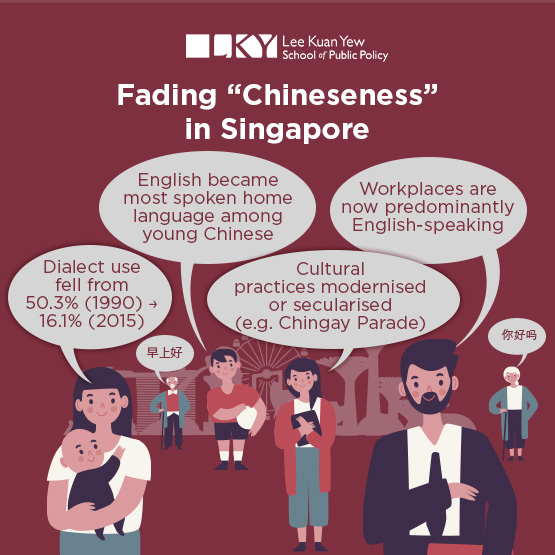

Yet an interesting observation is that many facets of "Chineseness" are nowhere as prominent in Singapore as they used to be in the past. Chinese dialects and even Mandarin Chinese are far less spoken among the younger generation, and workplaces are predominantly English-speaking environments.

In a study of Chinese Dialect Groups by the Singapore Department of Statistics, it was noted that the number of Singaporean Chinese residents who spoke dialects as their most frequently used language declined from 50.3% to 30.7% between 1990 and 2000. In 2015, the number fell further, from 30.7% to 16.1%. Furthermore, English was the home language for 52% of Singaporean Chinese residents aged 5-14 years.

There is little evidence to suggest that this trend will change. In fact, the relevance of Mandarin Chinese is also diminishing; in 2015, English officially overtook Mandarin Chinese as the language spoken most often at home in Singapore.

It comes as no surprise that many family-owned businesses that embodied "Chineseness" are gradually being phased out. A Straits Times article titled "Traditional businesses facing tough times" pointed out that the rising costs and increased competition make for worrying times for these businesses, such as traditional confectionary, bookstores and antique shops.

The notion that "Chineseness" helps to strengthen business ties is also no longer as applicable. In fact, as English slowly replaced Mandarin as the main medium in workplaces and Western corporate culture superseded Chinese business practices, many successful family-owned businesses have sought to modernise. Prominent examples of this phenomenon are Eu Yang Sang and Yeo's Singapore.

Chinese traditions and religious practices also feature less in today's society. While important events such as Chinese New Year and the Chingay Parade are widely celebrated, they have become secularised. This could be attributed to the decline in adherents of Taoism and folk religion, from 30.0% in 1980 to 10.0% in 2015. Chinese folk rituals are also more prominently observed among the older generation, with only 6.3% of residents aged 15-24 adhering to Taoism.

In addition to featuring less in society, Chinese religion is being practised in different forms. Traditionally, adherents of syncretic Chinese religions are expected to participate in religious rituals and processions. Yet, there is an observation that some of these practices have been transfigured and hybridised. For example, the Chingay parade has become a state-sponsored nation-building float procession. According to Goh, by moving the parade date from coinciding with the Hungry Ghost Festival to Chinese New Year, the practice appears to now embody a secular Chinese identity. Moreover, the religious heading of the parade, which was once a spirit-medium in trance leading the floats, has been replaced by the Chinese Lion Dance, which lacks religious significance.

Nonetheless, this does not necessarily imply that Chinese religions will become extinct. Rather, it highlights how Chinese religious forms can be easily transfigured into a "modern-day aesthetic display".

At an impasse

The aforementioned observations demonstrate that what was commonly associated with traditional Chinese culture is slowly fading into the background. We are faced with a dilemma – we can no longer identify with this diasporic Chinese identity as much as our ancestors once did. Yet, we struggle to relate fully with Western culture.

In a blog post entitled "Should English be the Mother Tongue of Chinese Singaporeans", the author summarised my thoughts succinctly by stating that, "I have always considered English as the language of the Westerners, belonging to foreigners. I have merely borrowed and adopted it for the long term – It does not belong to me". Yet, this sentiment clearly contradicts the nation's language policy and its outcomes. While one of our state-issued mother tongues is Mandarin, most of us are sub-par in the language at best and an increasing number of Chinese Singaporeans grow up speaking English instead.

So, what exactly is our mother tongue? According to Professor Tan Ying-Ying, one's mother tongue is determined by several factors: (1) what is the first language to which I was exposed from birth; (2) what is the language in which I am the most proficient; (3) what is the language I use the most; (4) what is the language that I would say is mine.

Based on this, it would be difficult for many Singaporean Chinese to conclude that Mandarin is their mother tongue. Clearly, contrary to state policy, one's mother tongue cannot simply be the language that is commonly associated with their ethnicity and/or community. In fact, Mandarin was not even the mother tongue of our grandparents (and to a lesser extent, our parents), most of whom grew up speaking the various Chinese dialects between the 1940s and 1970s. Effectively, we are at an impasse – uncomfortable with our state-issued mother tongue, but being unable to identify fully with the English language.

The government's emphasis on the English language as the main medium of instruction in the 1960s and 1970s, coupled with the "Speak Mandarin" campaign that discouraged the usage of dialects has artificially forced younger generations to adopt English as their main language due to practical reasons, both at home and in the workplace. A parallel can be drawn to how our ancestors maintained their "Chineseness" for practical reasons.

Likewise, the introduction of religions such as Christianity, as well as Agnosticism and Atheism have eroded the influence of Chinese folk religions.

A "Singaporean" identity in the 21st Century?

Thankfully, the concept of cultural identity is fluid and ever-changing. In the present day, we are neither "Chinese" nor "Western". Instead, an amalgamation of government policies, a culturally-diverse society, ancestral traditions and ideas from the West has allowed the adaptable Singaporean to develop their own unique identity.

What this means is that the "Singaporean" identity for a Singaporean Chinese borrows ideas from "Chineseness", but is remarkably distinct as it is also influenced by other cultures, languages and even government policies. One simply needs to point to the prevalence of Singlish, the nation's lingua franca, and its importance to our identity. Singlish, an English-based creole language, borrows words from many Chinese dialects but is also heavily influenced by Mandarin, Malay and Tamil.

Moreover, the make-up of a "Singaporean" identity definitely differs from person to person. Notwithstanding the general erosion of "Chineseness", some may continue to use dialects more frequently and choose to continue participating in the rituals and customs of Chinese folk religions. Interestingly, this has not stopped us from relating to one another.

Racial and religious acceptance has been imbued in us since birth due to the education system's constant emphasis on multiracialism, one of the state's key ideologies. As such, regardless of our slight differences in beliefs, customs and practices, we are able to create a common "Singaporean" identity that everyone can attest to. In a foreign land, a Singaporean would be able to distinguish the voice of another fellow Singaporean and have a conversation that no one else would understand. During National Service, boys from all walks of life are able to crack jokes and share their life stories with one another.

Indeed, it appears as though two generations after the diaspora, we are better off holding a conversation with a stranger in Singapore than a relative from a distant land.

Embracing Change

Writing this article has allowed me to reflect greatly on what it means to be a Singaporean and how one should reconcile my "Chinese" identity with my "Singaporean" identity. However, just as how our forefathers adapted and recognised the importance of change, we should too. At the end of the day, the Singapore we know today is vastly different from the Singapore in the past. Naturally, cultures and national identity will evolve as well. If it did not, then Singapore's efforts at nation-building and promoting assimilation should be deemed as a failure.

Perhaps we should appreciate our origins but also come to terms that we are no longer "Chinese" but "Singaporean".

Photo by Christian Chen on Unsplash