Singapore prides itself on its world-renowned hawker culture, inscribing it on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2020. But decades of culinary expertise are at risk of fading, as experienced hawkers gradually retire and fewer new hawkers join the scene. The issue of hawker sustainability has gained renewed relevance post COVID-19. At the height of the pandemic in 2020, hawkers lost up to 50% of their business.

Challenges of the Hawker Trade

While hawking is fundamentally the running of a business with the goal of profit maximising, hawker food occupies a special place in Singapore for providing convenient and affordable meal options for the masses. It has been described as a “safety net” that “offer[s] good quality meals at almost Third World price[s]”.

A 2020 National Environment Agency report found that hawker stalls had been suffering from declining profit margins. In February 2022, food prices jumped 20.7% year-on-year, led by rising costs of vegetable oils and dairy products due to supply disruptions from the Russia-Ukraine war. Hawkers are faced with the dilemma of whether to raise prices but potentially lose customers to competitors, to keep prices unchanged and face the prospect of being unable to make ends meet, or to shrink portion sizes at the risk of consumer dissatisfaction. All of which entail unenviable trade-offs.

In addition, the median age for hawkers is increasing and stood at 60 years old in 2021. With many expected to retire in the coming decade, hawking is set to become a sunset industry unless successors are found. Yet, although 82.5% of hawker patrons in a survey bought from hawker centres at least once a week, 87.3% stated they do not want to be hawkers due to the “long working hours” and “no interest”. The unattractiveness of hawking as a job is unlikely to be reversed, since hawkers work long hours in a hot and humid environment and are perceived to earn modest incomes. This is contrary to two of the most important job considerations for young Singaporeans – pay adequacy and work conditions.

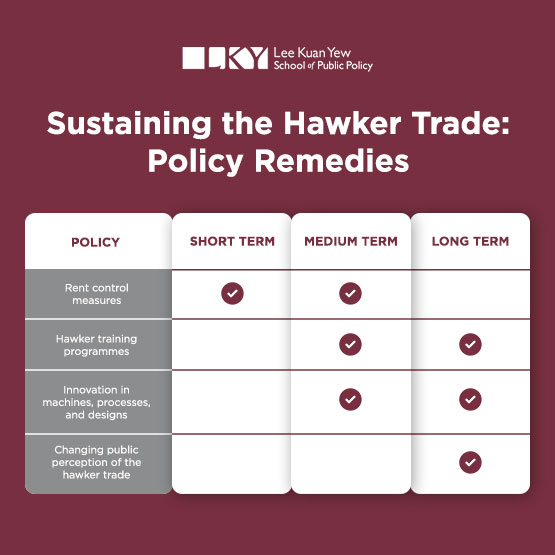

Policy Remedies

To sustain the hawking industry, the Singapore government has introduced various initiatives addressing the challenges that hawkers face.

Policy 1: Rent Control Measures

Under the current system, hawkers must submit bids for their preferred stalls under a monthly tender exercise. The bids are the monthly rental fees that bidders are willing to pay for the stall. The vacant stall will be awarded to the highest bidder. To ensure that rents remain affordable despite the bidding system, the National Environment Agency has adopted a two-pronged approach through both monetary control and non-monetary control measures.

Primarily, the government has ensured affordable rents through a system of subsidies and waivers. Stall owners in new hawker centres benefit from the Staggered Rent Scheme, which only collects a portion of rental in the first and second year of the hawker centre’s operations. In addition, older hawkers continue to benefit from subsidised rates that the government offered in the 70s and early 80s to encourage them to relocate from street hawking to hawker centres.

Separately, the government has also sought to prevent over-bidding by increasing transparency. Bidders may access a list of successful bids submitted in the past 12 months, providing them with a point of reference to submit reasonable bids.

The bidding system subjects hawker stall rents to market forces of demand and supply. As such, instances of high rentals will naturally occur from time to time.The system is primarily undergirded by the consideration of ensuring fairness and transparency in allocation of hawker stalls.However, the principle of market efficiency, where the highest bidders get the stalls, may run counter to the social role that hawkers play as a provider of affordable food.

Policy 2: Hawker Training Programmes

The current suite of policies comprising the (i) Hawker Incubation Stall Programme, (ii) Hawkers’ Development Programme and (iii) Hawkers Succession Scheme seek to increase the replacement rate of hawkers. The Incubation Stall Programme subsidises rental for new hawkers;

the Development Programme provides training to aspiring hawkers;and the Succession Scheme pairs veteran hawkers with potential successors.

While there has been some participation, the policies assume that sufficient numbers of people are already considering joining the hawker trade, when this is in fact a narrow demographic. A more sustainable approach should combat the negative perceptions associated with hawking, enticing those not already interested in the industry to consider becoming hawkers.

Policy 3: Innovation in Machines, Processes and Design

Authorities have also sought to resolve the issue through a series of innovation- and automation-related policies such as the Hawker’s Productivity Grant and Hawkers Go Digital Programme, which assists hawkers with acquiring automation equipment to increase productivity and raises awareness about online food delivery platforms to expand customer reach respectively.

Nonetheless, it must be noted that the high median age for the hawker industry necessarily impedes the adoption of digital technology due to the lack of digital literacy among the older population. Further, some food delivery platforms like Grab charge high commission fees of up to 30%, which eats into hawkers’ earnings.

Policy 4: Changing Public Perception of the Hawking Trade

It is key to consider how the public perception of hawker culture may be changed. Incentives are insufficient to “save an entire culture” and Singaporeans “must be ready to pay more for hawker food because it is valuable” and be willing to work in the hawking industry.

Singaporean hawker culture became the first successful local inscription on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity on 16 December 2020. This has resulted in an increase in recognition of Singaporean hawker culture, lending hope to the possibility that hawker food may instead be valued more for its unique “soft cultural power”.

In recent times, younger hawkers have been termed “hawkerpreneurs”, with the term making its way into Parliamentary discourse. Changing the language used around hawker work may assist in elevating the status of the trade. Even so, the nature of the hawking industry is fundamentally at odds with Singapore’s “emphasis on knowledge work over technical and services jobs”.

A sustainable solution to arrest the declining hawker trade will likely need to go beyond financial incentives and training opportunities, and include shifts in the mindset of Singaporeans and the discourse surrounding hawker culture. An apt starting point could be the UNESCO Representative List and the awareness and prestige it generated.

Read the case study Cooking or Cooked: The Future of Singapore’s Hawker Culture written by Khor Jia Wei and Kenneth Tan Zhe Kai, which was awarded the Distinguished Prize in the Case Writing Competition 2024/25 at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

Access more case studiesfrom the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

Copyright © 2024 by the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. All rights reserved. This publication can only be used for teaching purposes.