What might Asia look like in 2035?

Will the US maintain its supremacy in the region, or will its dominance be diminished? And what kind of regional order will emerge in its wake?

Panellists and experts, including members of Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP) international affairs faculty, met to share insights on these issues at the inaugural Festival of Ideas—a four-day forum organised by LKYSPP in November 2019.

Here, they offer some highlights from their thoughts on Asia’s strategic landscape in 2035—a timeframe far ahead enough to consider trends and possibilities beyond the present, without speculating too much about the future.

Professor Kanti Bajpai: Looking ahead to 2035, Asia will be unipolar again after a bipolar interlude. There’s a power shift in motion, and the region is moving towards a new spheres-of-influence future, with China at the top. A sphere of influence implies the dominant power:

- has an implicit if not explicit say in the international and internal affairs of regional states;

- can limit the regional influence of rival great powers; and

- sets the diplomatic, economic-technological and political standards in its sphere. If the rival great powers agree on the delimitation of their respective spheres of influence and can cooperate on global public goods, they could sustain a stable international order.

By 2035, China will not necessarily have surpassed the United States in nominal GDP terms, but the gap will have substantially closed. While the US may still be number one globally, we will see its influence in Asia greatly diminished—by virtue of geographical distance, cultural closeness, economic integration and growing Chinese power.

As for the smaller countries in Asia, Japan will have accepted that China is effectively number one in the region, economically and militarily. It will understand that the gap between China and Japan has grown too large and that accommodating China is necessary. Japan’s alliance with the US will be weakened. In the case of the Korean Peninsula, China might resolve the problem by extending security guarantees to both North and South Korea.

Fifteen years from now, Southeast Asia will have drifted even closer to China. Initiatives such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) inclusive of China, and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) will bind the region to China. Indonesia is on course to become an economic giant. It will grow to become the seventh largest economy in the world, with a GDP of over US$2 trillion by 2035. Its view of China will be vital. How comfortable will it be with Southeast Asia moving more firmly into China’s orbit?

India will have fallen further behind China by 2035. The GDP gap today is about US$11 trillion. In 15 years, the gap will be about US$20 trillion. The chances of India catching up with China are very slim. India has taken itself out of the RCEP. Its attitude towards a free and open Indo-Pacific is ambivalent, and it faces a host of internal challenges as well. All these will affect its influence in Southeast Asia.

If the rival great powers agree on the delimitation of their respective spheres of influence and can cooperate, they could sustain a stable international order.

Assistant Professor Selina Ho: I believe China will be the top dog in Asia by 2035, increasing its military strength and presence in the world as it advances. But I also see Japan rising over time and filling the gap left by the US. Southeast Asian countries think very highly of Japan: this is a very deep contrast to the way South Korea and China think of Japan. So this is an interesting element, and I think Southeast Asia will look towards Japan as a complement to China.

The second trend I foresee is that ASEAN will see its position diminished and will not be well placed to deal with the challenges of the 21st century. Climate change and migration issues are likely to affect ASEAN, and whether it can tackle these challenges is an open question.

The third trend is the rise in water conflicts, and Asia is likely to bear the brunt of this problem. This is mainly because the region is home to half of the world’s population and China is the “Water Tower of Asia”. With fast-paced economic growth, and high population growth and urbanisation rates, we’re going to see traditional security concerns intertwined with non-traditional concerns like water-related disputes.

Southeast Asian countries think very highly of Japan: this is a very deep contrast to the way South Korea and China think of Japan.

Based on these scenarios, I have three hopes. First, I hope ASEAN will step up, transform and assume leadership in solving some of the issues in the region. I’d like to see greater synergy between the US and ASEAN. Second, do we have to choose between the Chinese and the Americans? Can there be a third option? This is where I look to Japan as a possible counterweight to choosing between the two superpowers. My third hope is to see the greater use of technology to solve the environment and resource-related problems in the region such as water scarcity disputes between countries.

Assistant Professor Adam Liu: The year 2035 is very significant for China. In his 19th Party Congress speech, President Xi Jinping singled out this particular year as a milestone for Chinese development. In the same speech, he identified six areas China should focus on in its drive to achieving modernisation. I want to focus on two of these areas.

The first is China’s goal to become the next great power of tech innovation. My prediction for 2035 is that we could see a situation where the US and China become embroiled in a tech war, i.e., a head-on competition for first-mover advantage in various tech markets. As a result, smaller countries might be forced to choose between the two to pick a side. And I expect to see a continued global witch hunt against Chinese tech firms, as technological advantage can be translated into military advantage.

The China-US rivalry will be further exacerbated by China’s goal to extend its soft power globally, which brings me to my second point. The more China wishes to project its soft power around the world, the more it will feed into the clash of civilisations narrative that I see now emerging in the US.

We could see a situation where the US and China become embroiled in a head-on competition for first-mover advantage in tech markets.

But the one thing that people should really pay attention to in Asia is a potential conflict across the Taiwan Strait. If you look at President Xi’s recent speeches, it is clear that China’s overall Taiwan policy has changed from preventing independence to seeking reunification. I believe that President Xi has a strong sense of historical mission and, like any national leader would, he cares about his long-term legacy and wants to be remembered for achieving something really big. His best shot is Taiwan—to go down in history as the Chinese leader who made reunification happen.

Phred Dvorak: The trends in tech and tech finance that I’m seeing now can tell us something about where we might be in 15 years.

The first is the rise of Asia as a major source of capital and innovation for technology. There has already been a sea change in terms of venture finance— money going towards venture start-ups.

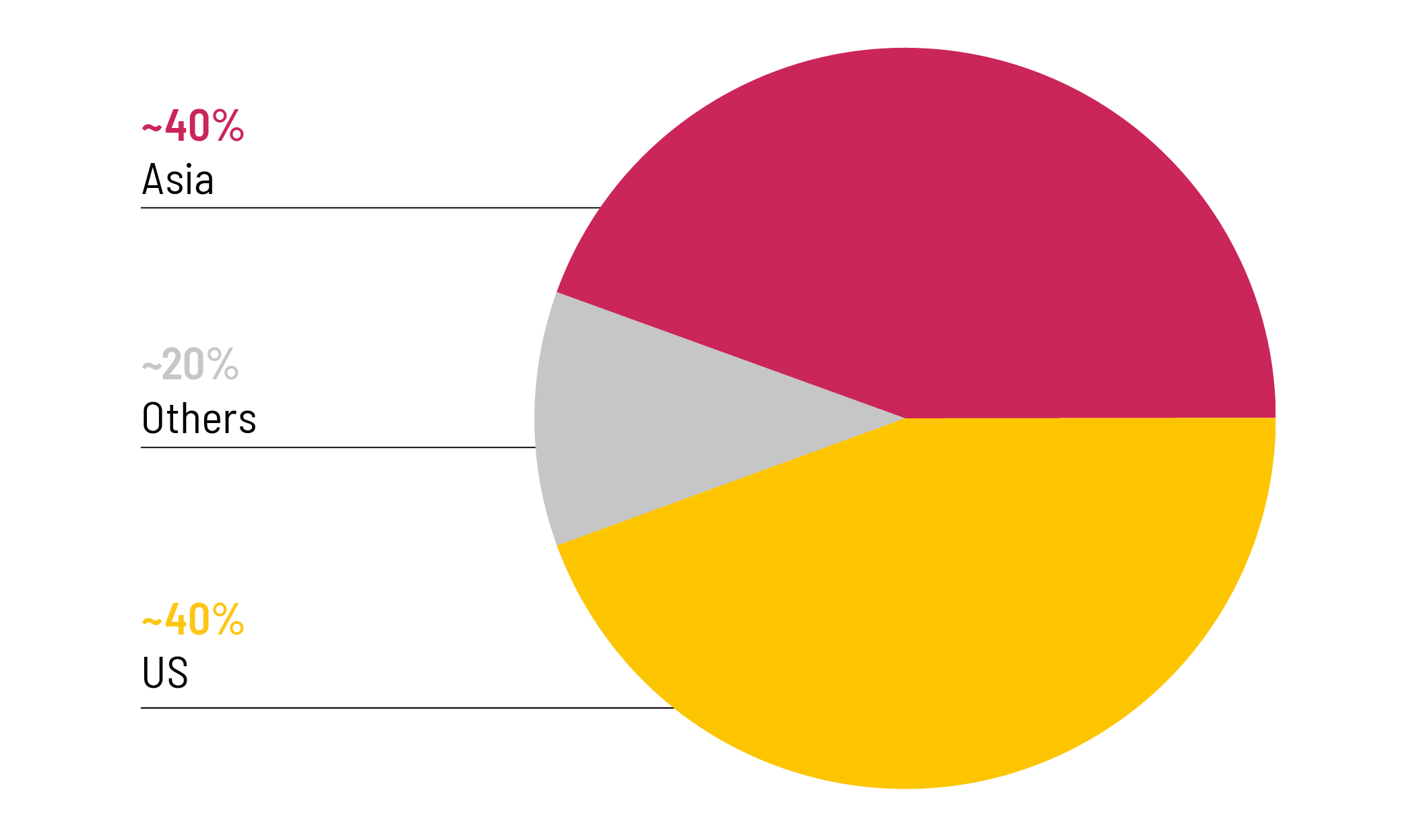

In 2005, the US provided close to three quarters of all the venture finance in the world, and Asia less than 4%. Last year, Asia accounted for around 40% of the world’s venture finance, nearly equal to the US. Significantly in the last few years, there’s been a lot of money from China and into companies in India and Southeast Asia. The same is also true for start-up growth.

Last year, Asia accounted for around 40% of the world’s venture finance, nearly equal to the US.

I think the trends which now show Asia roughly in balance with the US are going to tip in Asia’s favour in 15 years. So we’ll be in a multi-polar tech world when we think of technological innovation, tech and entrepreneurship.

Many companies in Asia are saying that Chinese and other Asian technology and internet services are much more relevant to them than the US’s models—as demonstrated by e-commerce businesses like Lazada and Shopee in Southeast Asia or online payment services like Paytm in India, that bridge the gap between the online world and the offline retail market. All of these trends are likely to continue into 2035.

However, does that mean China is going to dominate in Southeast Asia and India? Even as we see Chinese tech giants such as Alibaba having a big presence in Asia, I do think there’s going to be some intense local resistance to them as well, and we aren’t going to be seeing a complete dominance by them.

Even as we see Chinese tech giants such as Alibaba having a big presence in Asia, there’s going to be some intense local resistance to them as well.

Assistant Professor Marina Kaneti: I want to focus on the question of movement of people. Generally, we can think of movement under two broad categories: unregulated and regulated. The former is typically understood as movement that happens outside government prerogatives, and is associated with refugees, asylum seekers, undocumented migrants, internal displacement, trafficking, etc. The latter is usually a reference to movement that has been approved by respective governments for the purposes of short- or long-term stay of persons on a foreign territory.

These two broad types of movement are certainly observable in Asia (as everywhere else), and we don’t have to be fortune-tellers in claiming that both types of movement will continue to happen over the course of the next 15 years. This is the reason why, in thinking of Asia in 2035, I want to focus on the impact of these two types of movement.

Let’s look at unregulated movement. According to both the United Nations assessment reports and environmental specialists more broadly, Asia is the most natural disaster-prone region in the world. This, combined with various projections on the rising sea levels and virtual disappearance of vast patches of coastal areas, means that we are about to witness unprecedented levels of mass migration across Asia—migrations of the type that we have not seen in centuries (if ever). No government in Asia is prepared to handle that. In fact, as various migration crises in the region have already indicated, Asian governments are woefully unprepared to deal with the unregulated movement of people, let alone the type of mass exodus from areas that have been impacted by climate change.

So what does that mean for future prospects? Let me just focus on a very grim one. If other regions are at all an indication on how unregulated movement is handled by governments today, my prediction is that the Asia of 2035 will be replete with detention centres where people will languish in limbo, stuck between government incapacity and community indifference to their livelihood and existence. This is already the reality in North America, Europe, and parts of (North) Africa.

We live in an age where movement—whether regulated or unregulated—tends to produce fear, opposition, and further restrictions.

Let me turn to regulated movement, in an attempt at a slightly less pessimistic prediction. The trend is already here, but Asia in 2035 will continue seeing an explosion of tourism (i.e., one version of regulated movement). More Asian people will be on the move, travelling for short periods of time, to various destinations of their choice, on visas approved through bilateral government agreements. Asia in 2035 will especially see a massive increase of Chinese tourists. Why? Even today the number of Chinese tourists abroad is quite staggering—in 2017 alone, there were 131 million Chinese tourists travelling aboard. This is from a time when roughly only 10% of the Chinese population had travel documents, such as a foreign passport. My point is that governments are woefully unprepared to deal with the consequences of tourism-related leisure and entertainment, particularly in terms of the amount of material consumption, strain on resources, and capacity to preserve natural and cultural sites. Similarly, governments are unprepared to deal with local backlash, opposition, and discontent from tourism where the tourist can also easily become a racial “other”. Tourism, as a type of regulated movement encouraged for the purpose of profit-making, will have a dire impact on local communities and natural resources across the region and beyond.

We live in an age where movement—whether regulated or unregulated–tends to produce fear, opposition, and further restrictions. There is much that can be done to mitigate such processes and ensure that the movement of people is seen for its benefits and opportunities. The nature of Asia as a region suggests that movement is and will continue to be a critical part of every aspect of life for people in the region. Understanding and addressing challenges and impact associated with the movement of people should be a top priority for governments, institutions, and communities alike.

Republished with permission from Professor Kanti Bajpai, Assistant Professor Selina Ho, Assistant Professor Adam Liu, Assistant Professor Marina Kaneti, Phred Dvorak and the Civil Service College, Singapore. First published in ETHOS Digital Issue Special Edition, December 2020.