The pandemic has seen huge expansions in the power of the state enabled by new technologies — governments have locked down citizens, mobilised health systems and spent huge sums to support workers and businesses.

But is this a permanent or temporary shift, and what does this mean for Asian economies with traditions of frugal and limited states? How will political leaders balance calls for greater state power to monitor public health and reduce inequality while protecting individual privacy?

In the third instalment of Asia Thinker Series: Talkback moderated by Associate Professor in Practice James Crabtree from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, Senior Minister (SM) Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Mr John Micklethwait, and Ms Rana Foroohar discussed state capacity, trust, and privacy in the post-COVID-19 era.

The challenges ahead

Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Singapore Senior Minister and Coordinating Minister for Social Policies

Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Singapore Senior Minister and Coordinating Minister for Social Policies

Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Senior Minister and Coordinating Minister for Social Policies in Singapore, began by laying out the challenges most societies will face.

“First, we have a very real prospect of entering a world of secular stagnation,” he said. Economic growth will be slow, and wages are likely to stagnate, especially for the middle majority.

Secondly, most societies will struggle with “providing a fair deal for people”. “There is a loss of confidence that either the government or the market can provide a fair deal,” he said. Some societies, such as Sweden and Singapore, have been more successful in providing a fair deal by ensuring a significant wage improvement for the median worker. But generally, fair deals have been “elusive”.

The third global challenge is how we deal with our ageing societies. “In general, the world is unprepared for ageing societies,” he said. “Unprepared with regard to sustainable healthcare, financing schemes, [and] pension schemes.”

Climate change is another existential problem for societies, which will complicate all the other challenges societies are currently facing, said SM Tharman.

He believes that the way we think about the post-COVID-19 world should not be so different from how we viewed the world before. The challenges had always been present; COVID-19 simply intensified, complicated and sped up these pre-existing challenges.

But if governments want to address these challenges effectively, they would have to change their ways.

A new social compact

SM Tharman believes that the markets alone cannot solve these issues. He argued that governments cannot merely rely on spending more to tackle these challenges as it is unfeasible and ineffective.

“Fundamentally, we need a new compact between state and markets, [and] state and community,” he said. This new social compact should make the most out of the entrepreneurship and innovation offered in the markets not just for private gain, but also for public purpose.

It is a fundamental fiscal policy challenge to use markets and the private sector to develop public goods, he said. He elaborated that using the private sector to “serve the public purpose” should be the fundamental approach when thinking about the role of the government.

Governments also need to empower communities, institutions, employers and social networks to “regenerate themselves in larger societies”. Redistribution, which was the old system, was not effective as it doesn’t give people “a sense of true inclusiveness”.

According to SM Tharman, the problem is that “redistribution was too much about compensating the losers” instead of helping people regrow and regenerate communities and individuals. Instead, a system that empowers people to come together to work with networks of people — such as companies and education institutions — is needed.

SM Tharman believes that collective responsibility is the compact that Singapore should strengthen and reinvigorate.

Instead of relying on the state or the community, a “compact of people” need to take “[play] an active role” and “take responsibility for their families". We need to take "collective responsibility" and "personal responsibility" simultaneously to create a better economic outcome and culture.

This is possible, he said, citing societies in the US who have thrived under such social compact.

“I think the crisis is leading to a refocusing on fundamentals,” he said. “If we can strengthen our social compacts, in whichever society we are in, [we’ll] have a better future.”

The trend towards bigger governments

Mr John Micklethwait, Editor-in-Chief, Bloomberg, views COVID-19 as a “test of the governments”. Countries in Asia have generally fared better than their Western counterparts, yet he debunked arguments that it is an issue of political ideologies.

“There is no real evidence that autocracies are better at [managing a pandemic],” he said. Good democracies such as New Zealand, South Korea, Germany and Singapore have done relatively well, while autocracies such as Russia struggled.

Rather, he suggested that people want a bigger government. During a pandemic, people rely on the governments to help them. “That is the ultimate reason [of the] state: to protect you.”

Due to the “force of history”, the formation of bigger governments is likely. There is a trend of governments increasing, with people wanting more interventions during crises and security states. With little pushback from the right as the left pushes for bigger governments, bigger governments will most probably emerge.

Normally, markets would restrain the states from becoming too big, but “magical money, where everyone can borrow” has reduced the normal restrictions that prevent bigger governments

The danger of debts

Mr Micklethwait believes bigger governments should not happen, as “the age of magical money [will] run out”, leading to debt and bankruptcies. Relying on “magical money” to boost economic growth is unsustainable.

This sentiment was echoed by SM Tharman. “At some point, there is a constraint and [a] burden that debt exerts on growth,” he said. Many government bonds that used to be regarded as “safe assets” by investors are now regarded as normal credit instruments due to a loss of investors’ confidence.

One of the reasons for confidence lost is mounting debts. The loss of investors’ confidence can lead to dire consequences, such as “large movements in interest rates” and “the cycle of instability”. This happened in Greece, and SM Tharman fears that this will happen in developed countries that were thought to be relatively stable.

Mr Micklethwait believes that there is no need for governments to become bigger, as size does not correlate to effectiveness. The pandemic has revealed many underlying problems that reflect the need for states to be reformed, he said, but he fears that the discourse will only centre around bigger governments rather than reinventing governments.

Bigger governments might be beneficial

Ms Rana Foroohar , Global Business Columnist, Financial Times, agreed that governments are likely to become bigger, but unlike Mr Micklethwait, she believes that this is a positive change.

Since the beginning of time, there are cycles of wealth accumulation and wealth distribution, she said. She believes that COVID-19 has pushed economies to “a tipping point where the fortunes of Wall Street and Main Street are going to reconnect”, leading to “further market correction”.

She hypothesised that this is where the governments will step in, regulating and hopefully creating a “productive bubble around something like green technology”. “It tends to be the government [laying] the foundations for a new area of growth that the private sector can then go into commercialise,” she said.

However, implementing easy money paradigms extensively for the Main Street, such as quantitative easing, is likely to be a mistake as it would erode trust. Instead, Ms Foroohar hopes to see “higher taxes on corporations and the wealthy”, an “elimination of loopholes”, and “a cleaning up of some of the problems that led to the populist politics that we have now [that has] created this lack of trust in the government.”

“And I think that is going to be the big question. Can governments regain trust, [and] will the leaders make the right policy decisions in order to do that?”

Trust and the healthcare system

SM Tharman and Ms Foroohar both cited trust as a crucial factor when managing crises.

“Trust, which is hard to measure as it is intangible, turns out to be the critical determinant of how well we can manage crisis like a pandemic,” SM Tharman said.

Cooperation is necessary for contact tracing, which requires a lot of manual effort and is “really a social network”. People have to be willing to “do something personal that is socially responsible”, such as being tested frequently and wearing masks. These arrangements require a high degree of trust in states, he said.

To build a good healthcare system, which is crucial to contain the pandemic, a public sector role in healthcare is necessary. Singapore has a strong public sector dominated healthcare system which coordinates with private clinics.

“Just like in education, healthcare is a public good, and the public sector has to be a large anchor-provider within the healthcare system,” SM Tharman said. This way, the quality of healthcare can be raised, yet maintain at an equitable and affordable level.

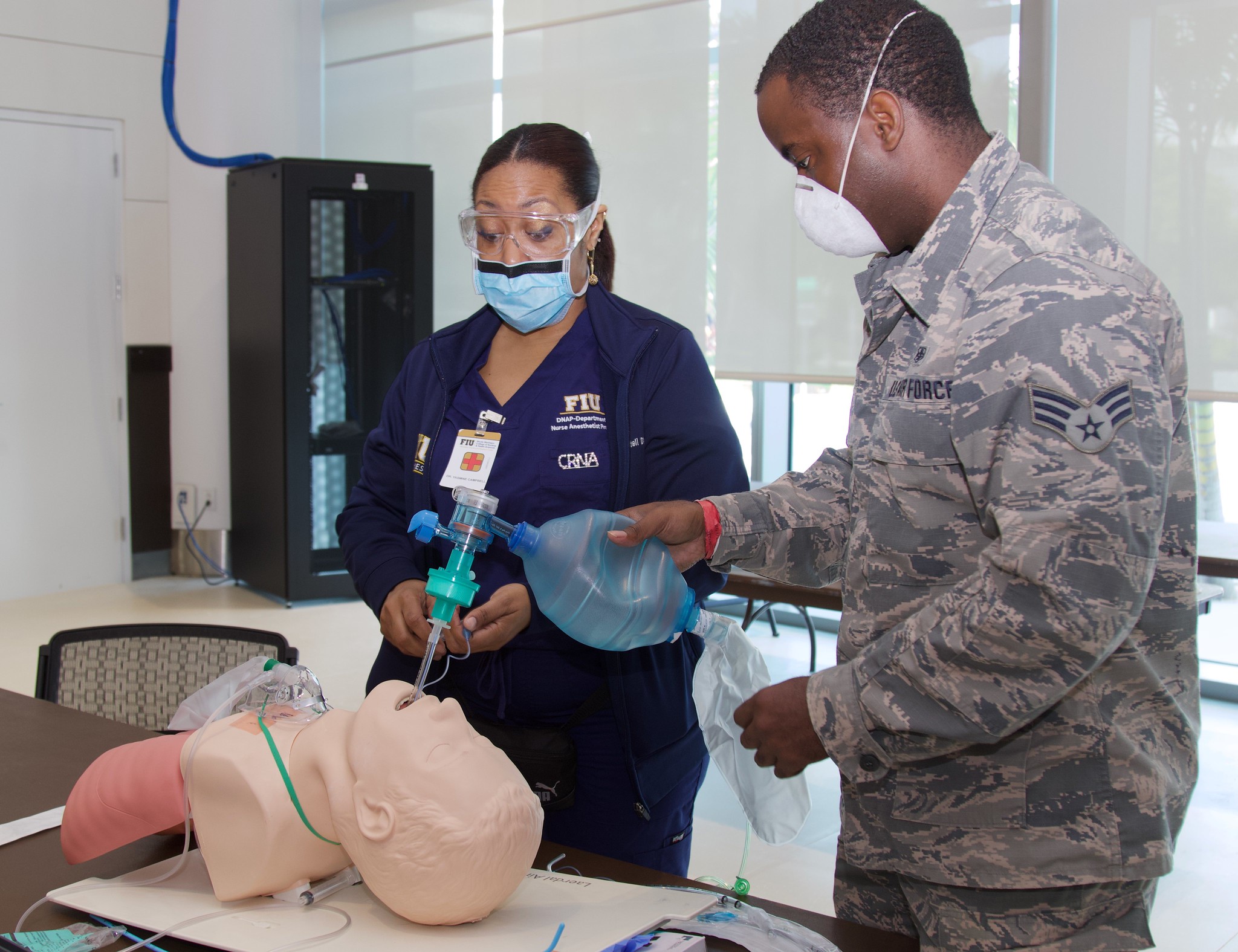

Healthcare workers in the US state of Florida conduct refresher training in preparation for COVID-19 patients (Photo: Sgt. Leia Tascarini)

Healthcare workers in the US state of Florida conduct refresher training in preparation for COVID-19 patients (Photo: Sgt. Leia Tascarini)

Good leadership is also important, added Mr Micklethwait. The US and UK had leadership that failed with managing the pandemic. “What matters is how you react to [crises],” he said.

Even though the US spends more on public healthcare than countries such as Sweden, it is significantly less effective. According to Mr Micklethwait, this stems from the US government’s inability to learn from what other states are doing. Another problem was that the American healthcare system was largely designed “for old, rich people, and dealing with their problems”, rather than for the public health.

On the other extreme, the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), which catered to everyone, did not fare well as they “did not draw on private testing facilities” in the way that other countries’ public systems did. This led to an overloading of their public healthcare system.

Mr Micklethwait drew this back to the importance of trust and competence. “If you have no trust in your government, you are unlikely to do what people tell you to do,” he said.

The importance of cooperation and coordination between the public and private sectors was also highlighted by Ms Foroohar. Due to the lack of coordination in the US, production levels were hampered as clothing factories who wanted to produce masks did not know how to do so, with little aid given.

In contrast, Germany had good cooperation between the private and public sectors, which led to a quicker economic recovery after a crisis. According to Ms Foroohar, if countries wish to recover as quickly after a crisis, economic strategies need to move away from “efficiency” and towards “resiliency”.

The activist state

SM Tharman emphasised on the importance of effective states - or states that can “achieve outcomes efficiently in an inclusive fashion”. This requires “activism on the part of the government”.

He said that large states are not necessary, but “a system of having faith in activism on the part of the government [and] having a sense of moral purpose in [our] government” are needed.

“You don’t have to be very large, but you have to be very good at the most important things you should be doing, and go about it with the spirit of an activist,” he said. This is necessary to build liveable cities and achieve equality.

States need to be able to focus resources onto “what matters most, rather than on everything”. An effective state is one that leverages on the private sector and on communities to provide public goods reliably. Currently, a fundamental priority of states is to “re-centre government and fiscal policy on the provision of public goods”.

He also cited the education system as one of the “most fundamental failings of societies and governments that have not been able to achieve inclusive growth” due to the high inequality in the education system.

Rather than size, the solution lies in rethinking how societies are organised, and how the states ensure that everyone plays a responsible role and feels that they are contributing. “That’s a truly progressive culture, rather than those that rest very largely on redistribution,” said SM Tharman.

He elaborated that another consideration is about fairness: who pays the costs, and who reaps the benefit. Going forward, the governments will have to become more progressive, in the sense that the wealthier will have to make more contributions. Greater support must also be given to the less well-off.

“Everyone should contribute something more as societies get older, but fairness dictates that things have to stack up in favour of the poor and the middle income,” he said. Even though Singapore does not have a large government, it is “a highly progressive government in healthcare, education… [and] social security”, and SM Tharman believed that this will further improve in the future.

Unemployment and jobs

SM Tharman emphasised the importance of “[getting] people into jobs sooner” after being unemployed, as staying unemployed for long can cause skills to fade and reduce individuals’ employability. Even though job skills stay relevant in the future, it often needs to be supplemented with new skills.

The pandemic has made upskilling and reskilling a more “urgent” task. Governments need to “move much faster” in preparing people for the next available job in a context where the global demand for permanent jobs are low.

In Singapore, the government implemented schemes such as “subsidising attachments and traineeships influence so that people are in real firms doing real work even if they're not on a permanent job yet”. Incentives for hiring permanent staff have also been strengthened.

According to SM Tharman, unemployment insurance schemes are unnecessary if active labour market policies are implemented well. “If we fail and, over time, we find we have high structural unemployment, [then we’ll] need some form of unemployment benefit scheme,” he said.

Currently, the government has kept Singapore’s unemployment rate low due to their ability to coordinate with people and the private sector quickly and efficiently.

“And that, too, is what we were talking about earlier. It's about state capacity, it's about coordination, and it's about trust between players.”

Watch the full recording of After the Pandemic: The Rebirth of Big Government? State Capacity, Trust and Privacy in the Post-COVID-19 Era below: