The ASEAN model has worked well for its member countries in recent decades. For continued success, however, ASEAN leaders must better manage risks that could potentially destabilise the region.

While the West endures greater political uncertainty, ASEAN celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, marking a milestone in efforts to improve growth and collaboration. However, to remain integrated and avoid suffering fragmentation similar to Europe, ASEAN policymakers must closely review any threats to its stability and improve collaboration to ensure sustainable growth in the region.

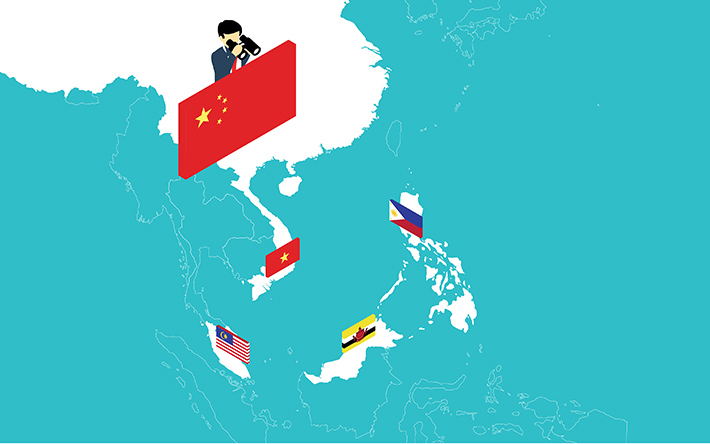

1. Territorial tussles in the South China Sea

The South China Sea dispute has caused increasing tensions due to militarisation by rival claimants such as Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia. This potential arms race is mostly caused by China's increasing aggressiveness in pursuing its own claim of sovereignty over the territories in question.

However, with ASEAN members being under China's influence to various extents, their dependence on China for trade and investment means much is at stake. Additionally, China has insisted that it will only negotiate with ASEAN countries individually instead of collectively, which weakens ASEAN's negotiating power as a regional bloc.

Failing to solve this territorial dispute would highlight ASEAN's inability to protect its members' security. Ministers have held talks on establishing a code of conduct (COC) to demilitarise the region for more than a decade, and a framework is expected to be in place by June 2017.

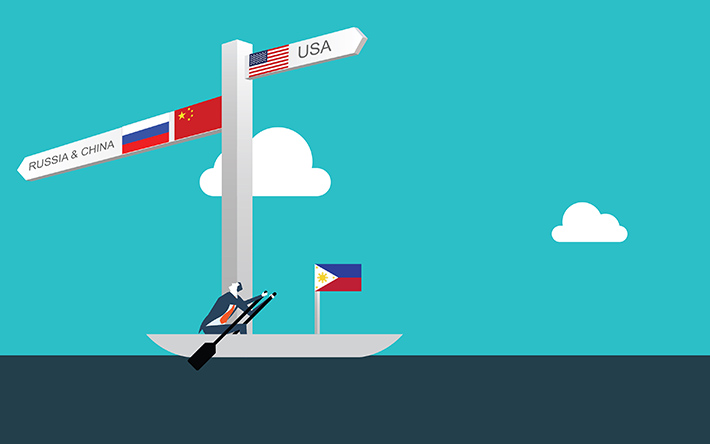

2. President Duterte's quest for independence, not interdependence

The Philippines has been appointed Chair of ASEAN for 2017. President Rodrigo Duterte's decision to pursue an independent foreign policy by realigning the Philippines' interests away from the U.S. and closer to those of China and Russia raises great concerns.

As Chair, showing partiality towards one dialogue partner, namely China, not only endangers ASEAN's efforts to build regional solidarity, but could also generate discontent among member countries. It is vital for the Chair to maintain the ASEAN principle of centrality.

President Duterte's nationalism could also potentially affect ASEAN-U.S. relations. Despite his seemingly cordial relationship with President Trump, Duterte's tendency to be vocal about his disdain for the U.S. could further alienate the new Trump administration, which has not yet articulated a clear policy regarding ASEAN.

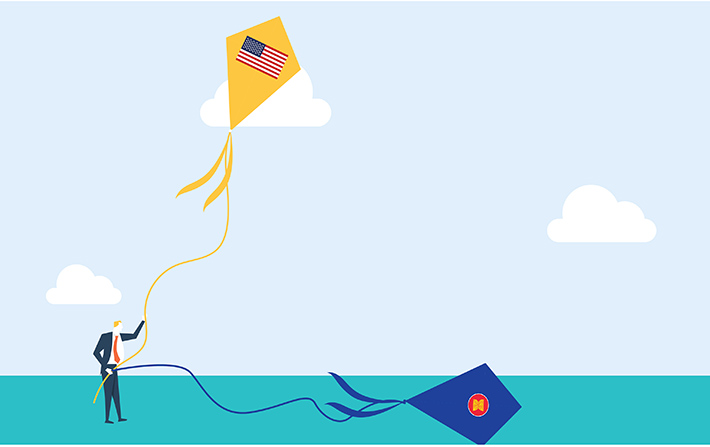

3. U.S. disengagement: A new global order?

President Trump's loosening of ties with Asia is another cause for concern in ASEAN. In 2013, the U.S.'s goods trade deficit with ASEAN was US$48 billion. But with the America First' policy, many ASEAN members that rely heavily on export, such as Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia, could be affected if the U.S. adopts more protectionist measures.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was the first casualty of President Trump's move towards isolationism. Razeen Sally, Associate Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore, stated at a recent panel that without U.S. leadership, the alternative could be an emergence of a more arbitrary form of capitalism, with more external manifestations of the internal Chinese order, which in many ways continues to be very nasty indeed.

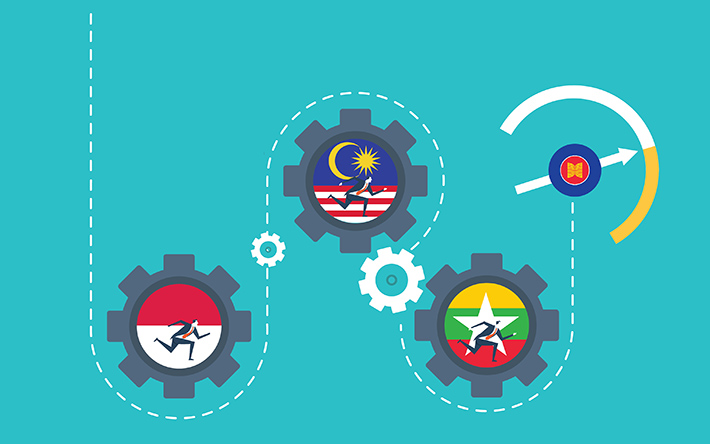

4. Internal struggles and their impact on regional stability

Individual ASEAN nations' focus on domestic challenges could take away ASEAN's collective efforts in regional growth. Myanmar's Rohingya crisis, Malaysia's 1MDB corruption scandal and religious strife in Indonesia due to Jakarta Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama's trial are just some of the political issues that could upset stability in the region.

However, ASEAN's principle of non-interference means that all the aforementioned problems have been prolonged without solutions. There have been rising tensions between member countries, as seen in Muslim-majority Malaysia's criticism of Myanmar's treatment of the Rohingya. ASEAN countries may need to rethink this principle if they wish to encourage greater cooperation and cohesion.

Regional stability by means of economic integration is also impeded by the diversity of economic and social systems between ASEAN members. Large income inequality gaps between the countries make it difficult for initiatives such as the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) to be implemented.

While middle-tier economies such as Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines are actively working on development plans to catch up with richer ASEAN countries, it remains to be seen whether other members such as Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar can do the same.

Ensuring success for the next 50 years

To ensure ASEAN's sustainable growth, a strong common policy is critical. As Singapore's Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong stated at the 29th ASEAN Summit Retreat in September 2016, ASEAN leaders must work closely by sharing intelligence and standing together on the South China Sea issue by means of a binding COC.

Furthermore, in order for initiatives such as the AEC to succeed, ASEAN policymakers should first focus on closing the income inequality gap by solving socio-political problems and taking care of disadvantaged populations. The members should also invest more in each other and encourage greater intra-ASEAN trade.

Despite the risks, Asian markets continue to grow, buoyed by alternative initiatives to the TPP such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and China's One Belt, One Road' policy. If successful, these initiatives may serve to deepen and strengthen Asia's trade channels and help ASEAN continue as a major player in the global economy.