While analyses of Chinese foreign policy have typically focused on Sino-US relations and Beijing’s diplomatic activisim in East and Southeast Asia since the end of the Cold War, an equally important area of Chinese foreign policy in transition is Beijing’s approaches toward the South Asian subcontinent. During the Cold War, and since the late 1950s until the late 1980s, Chinese diplomacy toward the region was largely driven by its animosity with India due to the unresolved territorial disputes. This informed a policy of supporting Pakistan in its conflict with India and making inroads into the region by providing military assistance to other South Asian states. With the end of the Cold War and the gradually improving bilateral ties with India, Chinese policy toward the region has shifted to focusing on developing political and economic ties with the region, especially as Beijing pursues its ambitious Belt & Road Initiative. This seminar examines the key drivers behind the shift of Chinese policy, recent developments of China-South Asia relations, and discusses the challenges ahead in the broader context of Chinese grand strategy under the current Xi Jinping leadership.

Event Coverage

China-India relations today are affected by a range of problems. These include territorial disputes, India’s support for the Dalai Lama, trade imbalances, the perception of each other as a threat especially after the Doklam standoff, Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), and the complex triangle relationships between China-India-United States (US) and China-India-Pakistan. These problems have led to miscommunication, misperceptions, misunderstanding, misapprehension, and miscalculation between the two countries. They can only be managed by better communication, confidence building measures, the seeking for common interests and common identity (such as the BRICS), as well as cooperation for win-win outcomes.

Both sides have taken steps towards developing a cooperative partnership. First of all, there have been frequent high-level visits by leaders of both countries. Secondly, bilateral trade had been growing from 1987’s USD 117 million to 2017’s historic high of USD 84.4 billion. In order to solve the border disputes, there have been mechanisms put in place to facilitate talks between the two countries’ special representatives. Between 2003 and 2018, there had already been 21 talks between the representatives from both sides. On top of that, there have also been regular consultation and dialogues on bilateral, regional, and global issues. Also, military exchanges have been conducted and a new defence Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) has been signed (Agreement on Border Defence Cooperation).

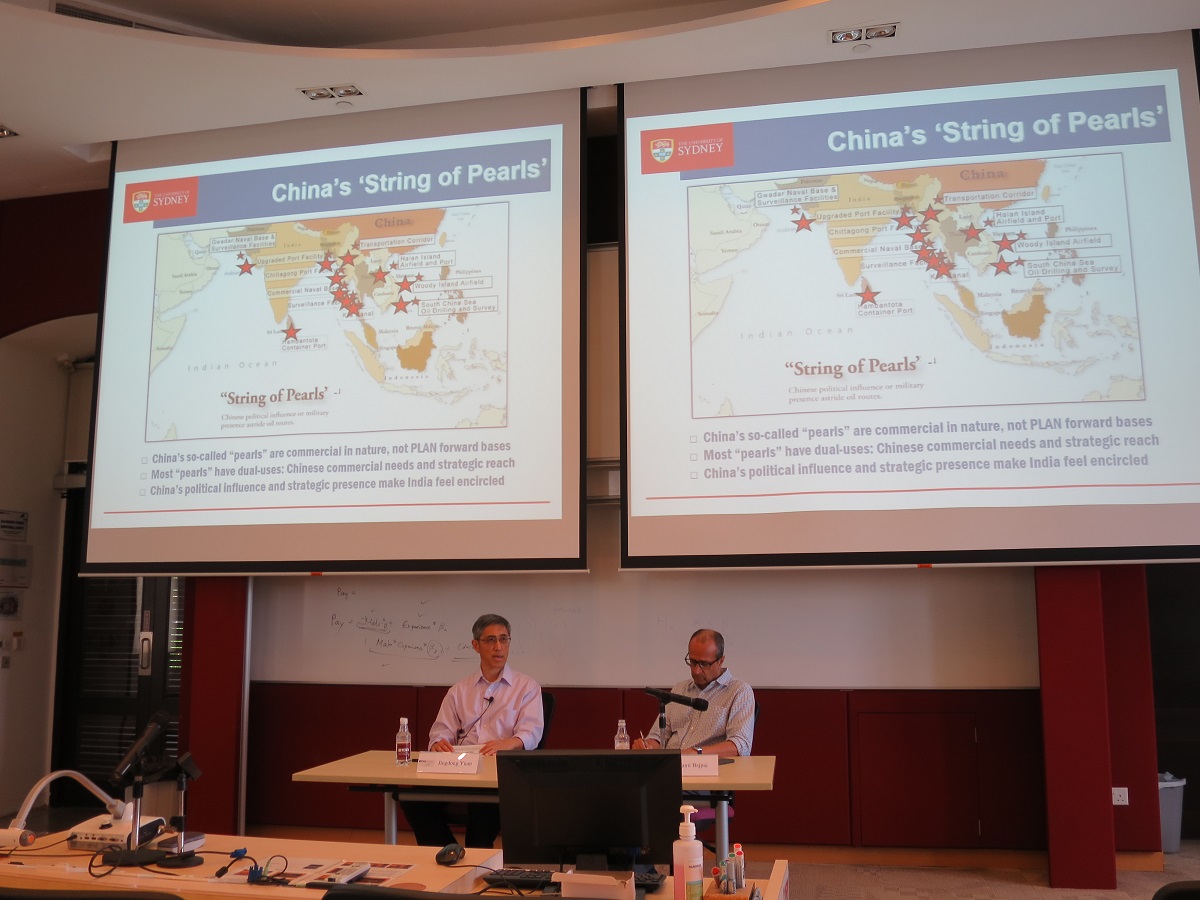

India has always seen South Asia as its sphere of influence. As China gradually but surely expands its presence in the IOR and South Asia, it is perceived as an attempt to encircle India through the so-called “String of Pearls” Strategy. The reason why China is shifting its attention to South Asia and the IOR is because of the region’s growing importance for China’s energy security and access to reliable and safe sea lines of communication (SLOC), ports, and inland transport routes. South Asia’s littoral states are well positioned in such a way that they could provide great convenience and security for China’s 21st Century Maritime Silk Road and its economic corridors. Since China is heavily reliant on imported oil, it becomes imperative for China to break the Malacca Dilemma and find alternative routes that could guarantee its supply of oil and gas. Hence, China finds it necessary to establish good relationships with South Asian countries, which it has been doing by increasing its trade and investment with these countries. Most importantly, Beijing has been investing in transport infrastructures such as roads and ports so that Chinese vehicles and vessels could also make use of them.

For example, there had been a deepening of economic ties between Sri Lanka and China during President Rajapaksa’s tenure from 2005 to 2015. One key Chinese-led project was the construction of the Hambantota Port, which was leased to China for 99 years as a way to service the Chinese debt. There have also been growing ties between China and Nepal. After the Nepalese earthquake in 2015, Chinese provided assistance and relief which amounted to USD 480 million. Another USD 8.3 billion has also been pledged for infrastructural investments in the country. China has also agreed to open its ports for Nepal, and extend the Qinghai-Tibet railway to Kathmandu near the Indian border, even though Indian ports remain logistically more feasible due to proximity. On top of that, there have also been defense exchanges and arms sales between the two. For Bangladesh, its relationship with China has been relatively stable since the 1970s. China has been constantly selling arms to Bangladesh, and with Bangladesh joining the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China has pledged new investments. However, in the Maldives, China and India are jostling for control and while China has been investing and assisting in infrastructural construction in the Maldives since the 1970s, India has provided financial assistance worth USD 1.4 billion to the Maldives since a pro-Indian government took over in late 2018.

China has come to realise the growing importance of South Asia especially in its critical place in the BRI. While Chinese presence in South Asia is mainly driven the objective of seeking friendly ties with neighbors, they have strategic implications for India, which sees China’s actions as attempts to dethrone India from being the dominant power of South Asia. It was also pointed out that South Asian politics can be volatile and Beijing has to learn to deal with domestic dynamics and seeks to expand ties beyond governmental exchanges. There are potential areas in which China and India could cooperate in South Asia, such as through the BCIM, ‘China-India Plus One’, as well as the role of the SAARC in accommodating both powers.

During Q & A, it was noted how China’s management of domestic politics in South Asia has evolved. Previously, it tended to support the host country’s ruling party in terms of political and financial support, earning the ire of the opposition. This inevitably caused problems for China if the opposition was installed as the new administration. Today, China is pursuing a more balanced approach, building up ties not just with the ruling but with opposition parties as well. However, this is also indicative of a deeper problem inherent in China – the lack of expertise on South Asia. Many Chinese who study foreign affairs tend to focus on more popular parts of the world like the US, Europe, or East Asia. South Asia has never been a popular region among Chinese academics so there is a lack of people who can give policy advice on the history and culture of these countries and their relations with China.

China’s connectivity push in the region has been driven by many factors. One is the huge amount of available funds that China wants to invest in places which can promise good returns. With respect to Pakistan, there’s a belief that improving the economic situation of its neighbour would help to stem the flow of extremism into China’s own restive Xinjiang province. Connectivity has also been seen as China’s attempt at soft power cultivation, by buying and attracting friends.

Port infrastructure in South Asia has little military utility to China. The Chinese navy would find it difficult to defend these ports due to the sheer distance involved. Nevertheless, such infrastructure has long-term importance to China given its growing dependency on energy imports. Moreover, the availability of ports and other facilitating infrastructure in states like Pakistan would open a more efficient route into China’s backward western regions, promoting development and bringing in investments.

China could also be motivated by ideational interests. For instance, projecting the positive image of the Chinese civilization, or traditional Chinese philosophies like Confucianism. In this respect, China has been grappling with the issue of its own status. Is it a great power comparable to the US? Or is it still evolving? This question has led China to behave in ways that can be considered similar to defensive realism. For instance, on the one-China policy, Beijing has actually adopted a minimalist stand with regards to Taiwan and the Dalai Lama.

If India is able to pursue a smart regional policy, it should be able to rally its neighbours to its side and push back Chinese influence. However, the problem is that India’s foreign policy has been inconsistent and it has flip-flopped on various issues. Moreover, it has sometimes taken a heavy-handed approach towards its smaller neighbours which have driven them into China’s arms. Many of the smaller states in South Asia recognise that both China and India represent key players of their region. Rather than hedging against one or the other, these states are carefully managing their ties with the two in a way that best serves their own national interests.

States in Southeast Asia could also be affected by China’s infrastructure projects in South Asia, both positively and negatively. The massive construction projects under the BRI create collaboration opportunities for companies in the region. For instance, the Port of Singapore Authority (PSA) was previously in charge of management and development of the Gwadar Port. On the other hand, there are concerns that if port like Hambantota and Gwadar ever became successful, they may compete with ports in Southeast Asia; though at the moment, these ports do not seem very viable.

While there has been much discussion about the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ (FOIP) being an anti-China containment strategy, Beijing has remained rather ambivalent to the idea. China sees itself as being ‘free and open’ in terms of neither obstructing the flow of maritime trade, nor freedom of navigation. It is open to new ideas, as well as open to markets. While China has not outright rejected the FOIP, it has its own concept of Asia-Pacific Security Cooperation, which emphasizes dialogue and consultation, peaceful development, partnerships, multilateral mechanisms, and sustainable security. China hopes that the FOIP does not signal a return to the cold war mentality which would be to the benefit of neither party, and indeed, none of the members in the region.