Amidst increasingly heated debates in Singapore on inequality, we look at an important tenet of governance in Singapore and whether it perpetuates existing rich-poor divides, to the detriment of lower-income Singaporeans.

The topic of inequality in Singapore is receiving increased attention these days thanks to Oxfam’s Commitment to Reducing Inequality index. Singapore ranked a dismal 149 out of 157 countries, in an index that measures efforts to tackle the gap between the rich and poor. Reasons cited for the low score include a relatively low level of public social spending on education, health and social protection, and a low maximum tax rate for the highest earners.

Anyone growing up in Singapore has been instilled with the notion that meritocracy is the country’s main principle of governance. One area that meritocracy is practised, is in Singapore's education system. In a meritocracy, everyone is allowed the opportunity to succeed based on the same tests, and the most talented are selected based on these nondiscriminatory challenges.

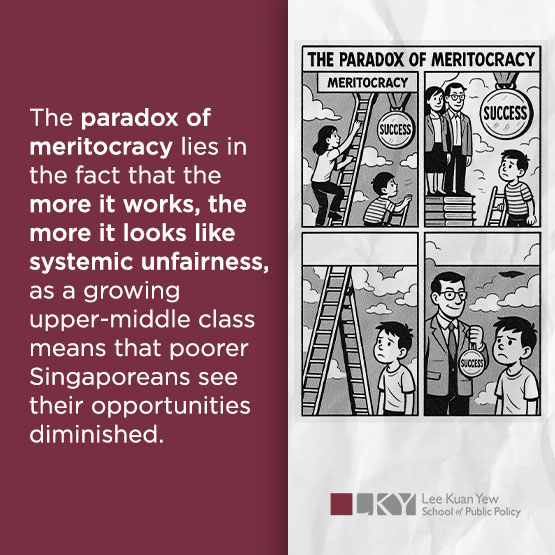

Although the meritocracy system in Singapore has created a large middle class by allowing upward social mobility amongst most Singaporeans, it also seems to have created structural and cultural conditions that reproduce inequality and elitism. Kenneth Paul Tan, Associate Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, has published a book titled Singapore: Identity, Brand, Power, which identifies some types of social inequality that Singaporeans face because of this system. We look at three aspects of life in Singapore that seem to suggest that meritocracy may no longer be serving its purpose, as it merely perpetuates existing class divides.

An education system that needs fixing

Singapore’s education system spurs students from lower socioeconomic status groups to gain upward mobility as it, in theory, provides equal opportunity by offering standardised testing. Education fees are affordable, with numerous grants provided for lower-income families, and rigorous standards enforced by the Ministry of Education on every school.

However, a report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reveals that the playing field is not as level as we would like to think so. The report, titled Equity in Education: Breaking Down Barriers to Social Mobility, states that in 2015, 46% of disadvantaged students in Singapore were attending "disadvantaged schools", up from 41% in 2009. Disadvantaged schools are defined as those which take in the bottom 25% of the student population, and poorer students in these schools face the disadvantage of not having access to the best resources.

Academic competition is incredibly intense in Singapore, and as families do better financially, they can afford to invest in their children’s talents through tuition or private coaching for extracurricular activities such as sports. As Education Minister Ong Ye Kung mentioned in a recent speech, the paradox of meritocracy lies in the fact that the more it works, the more it looks like systemic unfairness, as a growing upper-middle class means that poorer Singaporeans see their opportunities diminished.

Sports cars and cardboard boxes

Singapore was ranked the world’s most expensive city to live in for the fifth year in a row, in the Economic Intelligence Unit’s Worldwide Cost of Living 2018 survey. The decadent lifestyles depicted in the recent film ‘Crazy Rich Asians’ are not necessarily far from the truth.

What draws the wealthy to Singapore? Singapore’s status as a regional financial hub, its favourable conditions for living and business, and most importantly, low tax rates of 22% for top income earners. Fast cars and flashy lifestyles now abound in this little cosmopolitan city. Juxtaposed against images of elderly Singaporean cardboard collectors who struggle to make ends meet, the contrast is jarring.

The highest earners in Singapore compete for salaries that are internationally benchmarked, whilst the lowest earners experience downward pressures on their wages due to a burgeoning middle class and the influx of foreign workers. Since the mid-2000s, the government’s efforts to liberalise the economy has resulted in a dependence on low-wage migrant workers. Subsequent attempts to raise productivity have been met with dissent from small to medium-sized enterprises, who cite that they will be forced to raise prices or go out of business.

To add a further layer to the class divide, negative sentiment towards foreigners seems to be on the rise due to the influx of migrant workers. Rising discontent over the rapid increase in population and the perception that white-collar jobs are being stolen, have rendered these blue-collar workers invisible. Government policies that provide them with little social or economic security further worsens this.

Elitism and social segregation

Ultimately, these structural conditions perpetuate class divides. The Institute of Policy Studies’ (IPS) Study on Social Capital in Singapore shows that societal divides and inequality lie less along race or religion, and more along class. For example, on average, Singaporeans who live in public housing have fewer than one friend who lives in private housing. Additionally, those who attend elite schools also tend to have fewer friends in non-elite schools, and vice versa.

The reason why this occurs could lie in the principle of meritocracy itself. If one succeeds, they are perceived to have worked hard. Conversely, it is assumed that if one fails, it is because of a lack of effort. This leads people to disregard individual circumstances that may hinder one from succeeding in a one-size-fits-all education system.

The narrow focus on academic merit as an indicator of success only rewards those who excel in this aspect. For those not so academically-inclined, or for poorer students with less access to resources, the odds seem perpetually stacked against them.

This mindset extends to Singapore’s leadership. Ministers tend to be picked from a relatively small pool of those considered the cream of the crop, and salaries are amongst the highest in the world. In Singapore’s early years this may have allowed only the most talented to rise to these positions. However, as Professor Tan explains, Singaporeans today express discomfort at the ministers’ million-dollar-salaries and how public service motivations are now equated with the ‘profit motive’ of the private sector.

Bridging the gap

Education is the key tool to ensuring social mobility. Although the Singapore government has been providing large amounts of funding for lower-income families, Minister Ong has stated that more can be done to stop the trend of higher concentrations of disadvantaged students in certain schools to mitigate the issue of income inequality. For example, from next year onwards, a fifth of places in secondary schools will be reserved for students not from affiliated primary schools.

While meritocracy identifies those who are gifted early and rewards them with opportunities, the path accorded to these individuals in Singapore should not stifle the growth of late bloomers or those who excel in non-academic fields.

Singapore’s social fabric is at risk of becoming increasingly tenuous if existing inequality continues to entrench societal stratification. Meritocracy has been a key tenet of Singapore society, but it may be time for the current system of governance to address inequality to a greater degree than before. By moving away from a narrow focus on academic merit and recognising a broader range of talents and strengths, we may be able to narrow the divide by changing the way we provide opportunities, and more importantly, how we perceive others.