While much attention has been paid to the Chinese government’s efforts to restructure its economy, the state has been trying to push through wide-scale reforms to its pension system as it plans for an ageing population.

The country's 13th Five-Year Plan, unveiled by the Chinese State Council last year, revealed

policies for a unified, national pension system. This socioeconomic strategy will see the Chinese government consolidate dozens of funds currently run by local governments into a single scheme by 2020.

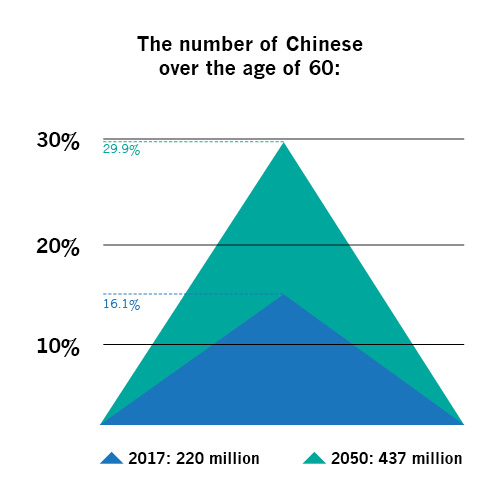

The proposal, among a slew of other measures, is aimed at building a sustainable pension system to insure the country against an ageing population. With 220 million people over the age of 60, this segment accounts for 16.1 per cent of China's total population at present. The number is likely to double by 2050, reaching more than 437 million, which will be nearly a third of the total population.

The absence of a comprehensive and sustainable pension system has already been a costly trend to the Chinese government. The overall annual expenditure for a mix bag of regional social insurance schemes increased from 2.3 trillion yuan (US$0.3 trillion) in 2012 to 3.9 trillion yuan (US$0.6 trillion) in 2015.

As a solution, China's National Council for Social Security Fund invested part of the country's 2 trillion yuan (US$0.3 trillion) of retirement savings funds in equities in 2015, followed by another 360 billion yuan (US$56 billion) of investments pumped into financial markets since late 2016. This was expected to help generate better returns for the pension funds rather than the government bonds that the citizens were previously limited to invest in.

Social concerns of an ageing population

However, the root problems of China's social security system go deeper than limited investment options, and can be attributed to two important developments in its socioeconomic history.

For one, the development and liberalisation of its economy in the 1990s and 2000s saw the break-up of the Chinese state-run economic model, which was an iron rice bowl for workers in the urban areas as it provided employment, housing, healthcare and pension. Secondly, the introduction of the one-child policy in the 1980s thinned families and deprived parents of a large extended family support structure in their old age. With a decline in the ability of its state and social structures to insure the future of workers in their old age, piecemeal local pension systems emerged to fill the vacuum left behind, albeit with varying outcomes.

Besides catering for an ageing population, there are other compelling circumstances that make the lure of a nationwide pension system attractive to the Chinese government.

For instance, unrest over social security concerns among workers in pockets of the country shows both the inadequacy of the current social security structures and the implications that could bring for social cohesion. The strike by around 40,000 workers at a shoe factory in Dongguan in April 2014 was triggered by employees who were underpaid social insurance contributions for years on end. This left thousands of workers with a rude shock of finding out that they were going to be paid a much smaller pension than they were entitled to.

The working class is yet to be the real beneficiary of the pension system in China, as the return is inappropriately low in comparison to their contributions, said David Wong Yau-kar, chairman of Hong Kong's Mandatory Provident Fund (MPF) Authority.

The nationwide pension system is also an attempt to address the Chinese government's growing concern of a regional divide between the affluent and less affluent regions of the country. For example, the Guangdong government reportedly earned a hefty 77 billion yuan (US$11 billion) pension surplus in 2014, according to areport by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. In contrast, the north-eastern province of Heilongjiang had a 10.6 billion yuan (US$1.5 billion) deficit at the end of 2014, making it one of seven regions to incur a pension deficit.

One reason for this phenomenon is self-inflicted by current policies that are misaligned with overarching national objectives. Migrant workers, for instance, must pay their pension contributions into the regional systems where they work, which tend to be the more developed areas. However, they are only eligible to enjoy the full retirement benefits of pension plans in their home provinces, likely to be the rural provinces. Thus, migrant workers may only have a portion of their pension contributions transferred to home from provinces where they work. A central pension system would be more effective in aligning its intent to provide cover for an ageing population as opposed to the current decentralised structure, which gets distracted with regional needs.

Challenges of integration and consensus

Despite the potential benefits of a nationwide single pension system, the government is likely to face strong resistance in pushing it through, which is not surprising since previous efforts to do so in 2011 under the 12th Five-Year Plan were thwarted by the regional governments.

Not all regional governments are supportive of the plans to migrate their pension systems into a national scheme, due in part to the income disparities between them. Many local governments have also been suspected to dip into their pension funds to finance other government projects.

In addition, as structures of pension contributions and payouts differ across regions, unifying them could create multiple problems such as determining what would be an equitable payout to all under a centralised scheme.

Although centralisation is aimed at eventually reducing administrative costs of managing different regional pension systems in the long run, the arduous process of harmonisation, which includes recordkeeping, communication and information exchange between

systems, could increase the administrative burden in the short term.

This imbalance has even caused uncertainty and anxiety about the plans for the countrywide pension system at a national level. China's Ministry of Finance is concerned that this system may overburden the central government with fiscal responsibilities

as the population ages. And their concerns are not baseless. According to figures of the Ministry of Finance, 12 per cent of the total amount of collected social insurance funds in 2014 came from government transfers, reflecting the fiscal strain that a national plan could pose.

China's Finance Minister Xiao Jie indicated that the problem was because in some regions pension payments exceeded collections.

He confirmed that local governments had been ordered to clean up their acts as the Ministry would ensure that all stakeholders are judicious once the new system comes into play. "The Ministry of Finance is responsible for properly managing every penny

of the pension," he said.

Pushing ahead with reforms

While the national pension system appears as a sustainable fiscal solution to China's growing grey population, resistance from local governments and concerns among the central agencies need to be overcome. Much will depend on how much political capital

the central government is willing to spend in going ahead with this unified system. For the time being, if reforms, like allowing portions of pension funds to be invested in financial markets, could help generate added sustainability, they should be

pursued.