Large swaths of Asia could have serious water shortages by 2050 due to economic and population growth and climate change , a 2016 study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology showed. To help avert this problem, nations in the region could learn

from Singapore's transformation in the past few decades.

In a recent research paper, Water Policy in Singapore, Dr Cecilia Tortajada and Dr Joost Buurman, senior research fellows at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, note that Singapore has changed from a water-scarce developing nation to a

world leader in water management.

The main reasons for its success include equal emphasis on water supply and demand management, long-term planning, strong political will to implement water plans, effective legal and regulatory frameworks, an experienced and motivated workforce, and the

management of the entire water cycle by a single national water agency, the PUB.

Turning on the taps

Singapore is one of the few countries that looks at water supply sources in their totality, and, in addition to quantity, takes into account other aspects of water such as its quality and production and management costs.

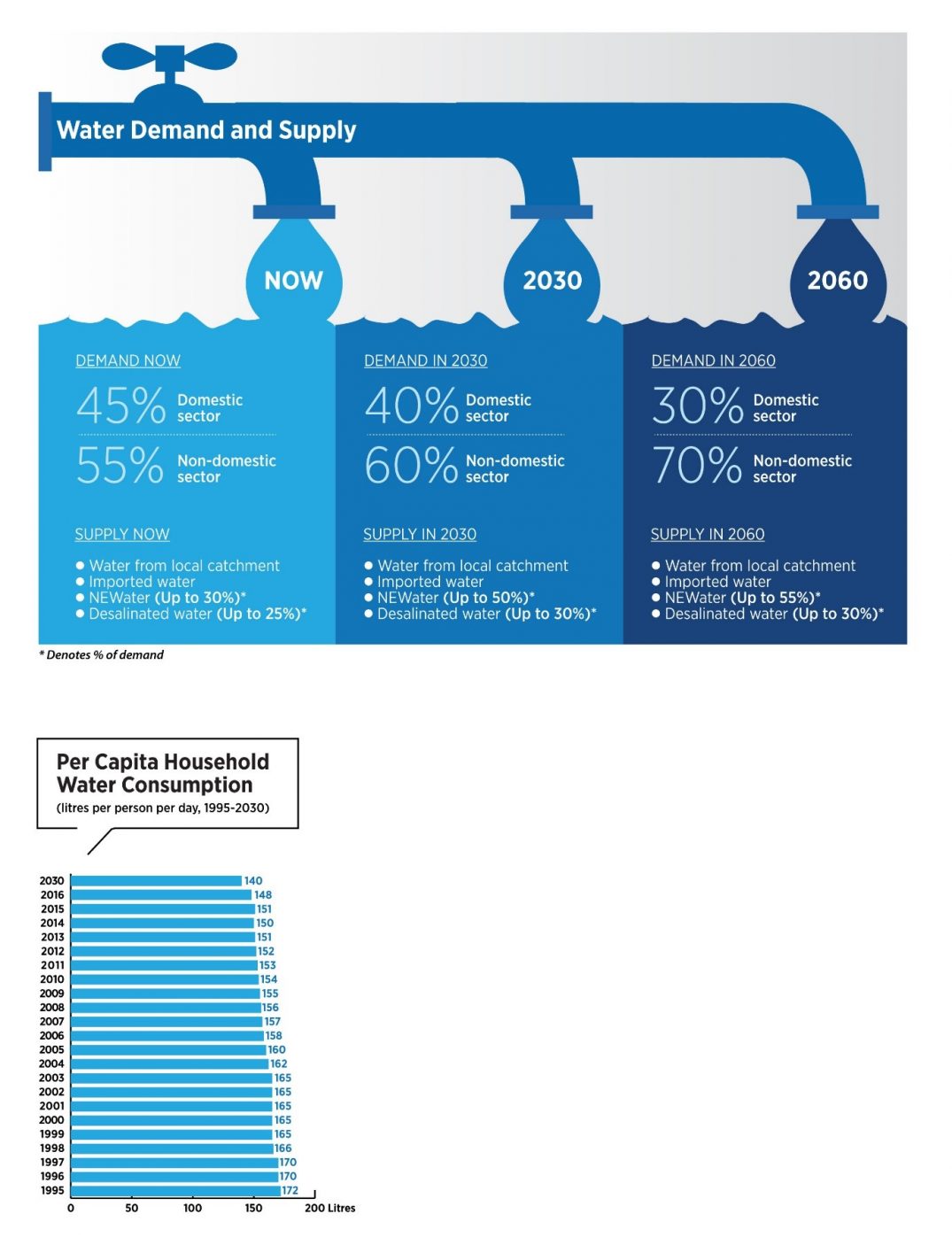

The city-state's 1972 Water Master Plan, for instance, outlined a diversified water resource portfolio to cover future water and development needs. Apart from collecting rainwater and importing water from Malaysia, the country has developed unconventional

sources of water such as recycled used water and desalinated water, resulting in a robust water supply system known as the Four National Taps.

Rainwater that falls on 65 percent of Singapore's land area is channelled to one of 17 reservoirs, and this catchment area will be increased to 90 percent in the long run. The Active, Beautiful and Clean Waters programme, launched in 2006, also helps

to slow the runoff and improve the water's quality through the use of water features such as bioretention ponds, bioswales and floating wetlands.

Since 2005, Singapore has opened two desalination plants, both in Tuas, that can meet up to 25 percent of its current water needs. A third desalination plant will be opened in 2017, and two more completed in the next 10 years, so that desalination can

supply up to 30 percent of the country's water demand in the long run.

Singapore also considered the possibility of recycling used water as early as the 1970s, and has opened five treatment plants to do so since 2000, after the technology's cost and reliability improved sufficiently. The ultra-clean, high-grade recycled

water, called NEWater, can now meet up to 40 percent of Singapore's water needs, and the plan is to increase this to 55 percent by 2060.

Singapore's last national tap is water imported from Malaysia, under an existing agreement, signed in 1962, that expires in 2061. Singapore aims to be water self-sufficient by then.

To further bolster its water security, the nation has also reduced its unaccounted-for water, including water lost due to leaks, from about 9.5 percent in 1990 to 5 percent in 2016, one of the lowest rates in the world.

Keeping a lid on demand

Supply, however, is only half of the water equation. By 2060, Singapore's water demand could almost double from the current 430 million gallons per day. To limit the increase, PUB has put in place comprehensive demand management policies that include

water pricing, conservation measures and public education.

A Water Conservation Tax was introduced in 1991, and a significant pricing revision in 1997 attempted to price water based on economic efficiency. The water price was pegged to the cost of desalination to reflect the higher price of alternative water supply sources, making Singapore one of the few places in the world to apply marginal-cost pricing.

While water prices did not change between 2000 and 2017, apart from the introduction of a separate tariff for NEWater, in 2017 the Singapore government announced a price increase of 30 percent, to be implemented over two years, to cover the increased costs of water supply. Low and middle-income households get vouchers which can be used for all utilities.

Since the late 1970s, PUB has also used engineering solutions to encourage water conservation. It has mandated the use of low-flow cisterns, introduced maximum allowable flow rates for taps and mixers, and launched a Water Efficiency Labelling Scheme for the sale of taps, mixers, urinals, clothes washing machines and other products. Only appliances and machines with acceptable efficiency ratings can be sold in Singapore.

Since 2015, organisations using more than 60,000 cubic metres of water per year are required to monitor their water use and submit Water Efficiency Management Plans to PUB annually. The agency also has a Water Efficiency Fund to support projects that improve water efficiency, and a Water Efficient Building certification scheme that encourages building owners to install water-efficiency fittings.

Public education is another key pillar of the water demand management strategy. Water conservation is part of the syllabus for primary school students, and education programmes and materials have been developed for foreign construction workers and domestic helpers.

Campaigns such as the 10-Litre Challenge, which aims to get people to reduce their daily water use by 10 litres, further inculcate the importance of saving water and provide people with the know-how to do so.

Beneficial partnerships

PUB is one of the few agencies in the world that manages all aspects of water resources, including management, supply, sanitation and drainage. Typically, such services are divided among two or more organisations, which can lead to problems if there is lack of coordination.

PUB also works extensively with the private and academic sectors to boost Singapore's overall expertise and efficiency in water technologies. Some of the key goals are to reduce the cost of desalination and NEWater production, increase the yield of water reclamation from 75 percent now to 90 percent and use seawater for industrial cooling.

The Ministry of Environment and Water Resources has set up an Environment & Water Industry Development Council, led by PUB and the Economic Development Board, to establish Singapore as a global hydrohub' and burnish its reputation as an epicentre of water-related business opportunities and expertise.

Currently, about 180 water-related companies and research organisations are based in Singapore, and the Singapore International Water Week, held biannually, is one of the largest global water conferences.

By ensuring the efficient use of its limited water resources through economic instruments, adopting the latest technology to produce more water, introducing water conservation measures and concurrently considering water's social, economic and environmental factors, Singapore has achieved an exemplary level of holistic water management. Its journey holds valuable lessons for other nations in the region.

*To read more, see the full paper Water Policy in Singapore.