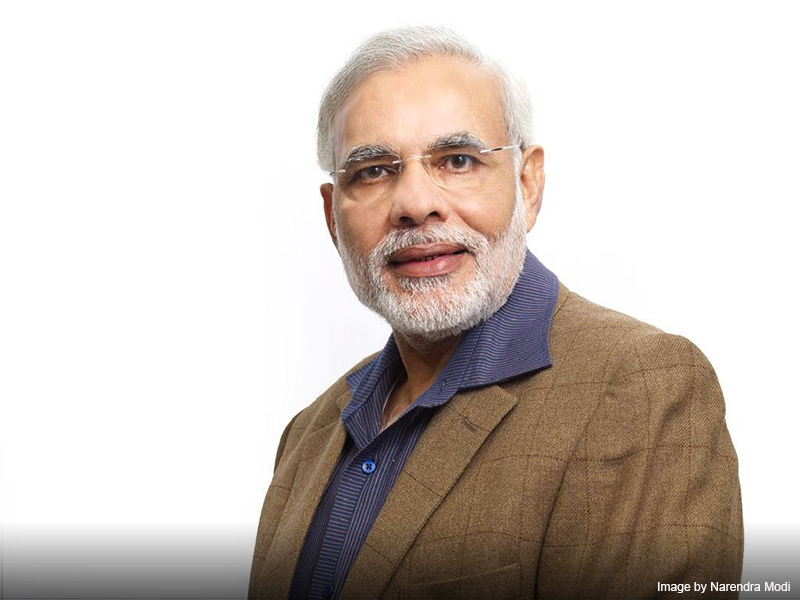

For all his many foreign visits and stadium speeches, Narendra Modi still lacks a defining international economic project. The recent attack in Uri scuppered one candidate, namely pushing greater economic integration across South Asia. But it has brought another into view: the Indian Ocean, and the idea of placing the wider region at the heart of a new neighbourhood policy for India itself.

September's terrorist attack has created an existential crisis for the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (Saarc), forcing the eight-nation body to cancel its meeting next month in Islamabad. Saarc is often viewed as ineffectual. Many observers are now asking whether its position has become untenable. Earlier this month, Sri Lankan Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe questioned whether the grouping could survive, musing that a body focused on the Indian Ocean should replace it.

This chimes fortuitously with ideas about India's neighbourhood floated recently by allies of Modi. The India Foundation, a think tank with links to both the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, held an Indian Ocean summit in Singapore last month which aimed to raise India's profile as a power with interests across Asia.

Parts of the event's agenda had a softer focuson cultural ties based on Hinduism and Buddhism. But there was a harder edge too, with India positioned as a counterweight to an increasingly assertive China. Foreign secretary S. Jaishankar argued in favour of reviving the Indian Ocean as a geopolitical concept, in a speech that appeared designed to lay down a marker against Chinese encroachment in the Bay of Bengal.

Modi has also talked up the importance of the Indian Ocean region, visiting a quartet of East African nations earlier this year, alongside trips to the Seychelles, Mauritius and Sri Lanka. But these Indian Ocean ambitions risk being distracted by narrow cultural concerns on the one hand, and vague geopolitical worries about China on the other. Instead, India should be focused squarely on the potential economic benefits from greater regional trade.

Here the opportunity is large, in theory at least. Research from Harvard University academic Ricardo Hausmann, which analyses the growth potential of nations based on the relative complexity of their economies, suggests that India will be the world's fastest growing nation in the decade to 2024, with its gross domestic product expanding by an average of 7% per year.

But of the world's six fastest growing economies over that same period, four will also be in east or southern Africa, including Kenya and Tanzania. A host of other countries likely to grow comparably quickly, not least Myanmar and Indonesia, are part of the wider region too.

This potential growth is already attracting corporate India, with groups like Tata and Mahindra targeting African markets. If Modi's Make In India export drive is to succeed, goods manufactured in domestic factories must seek buyers around eastern Africa and South-East Asia.

The problem is that while these nations are set to grow individually, the links between them are often feeble. South Asia is one of the world's least economically integrated regions. But the Indian Ocean, which encompasses roughly 40 nations and stretches from Australia to East Africa, is hardly any better connected. Estimates suggest that a third of global bulk cargo and two-thirds of oil shipments cross the Indian Ocean. But most of this heads off elsewhere, rather than being traded between countries in the region.

How might India improve this situation? The idea of creating a new regional body, or expanding an old one, is one approach being discussed. In his speech last month, Jaishankar floated the idea of expanding the Indian Ocean Rim Association, a low-profile grouping of 21 countries. This is better than nothing, but it has obvious drawbacks. If Saarc's flaw is that it's dominated excessively by India, an expanded Indian Ocean forum would suffer the opposite problem, bringing together a diffuse grouping with little in common.

The record of previous attempts to push alternative regional bodies is also hardly encouraging, not least the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation, whose six other members Modi has invited to meet alongside this week's Brics summit in Goa. Meanwhile, there is little evidence that regional bodies do much to improve trade flows in any case.

A better approach would see India making a bigger, unilateral push to improve regional connectivity, including greater financial support for new infrastructure investment, and a new push to reduce trade barriers, beginning with its own.

The success of China's grand One Belt, One Road initiative shows that tangible projects between countries are normally the best basis for new economic cooperation across regions. Here, India has work to do, be it pushing projects like the mooted Myanmar-Bangladesh-India gas pipeline, or providing greater development funding assistance to poorer neighbours.

The Indian Ocean has the potential to become the most important source of new global growth over the next 20 years, just as the Pacific rim powered the world's economy for much of the last 20. This fact alone should justify Modi placing much greater emphasis on it. But if India is to emerge at the heart of a new regional order, it needs to open its wallet first.

This piece first appeared in Live Mint.