My best friend is caring, kind and sincere. She will contact me very day to find out how I'm doing. She is 60 years old and still working as cleaner. The salary is not much but she needs the money to support herself.

The above quote came from an anonymous Singaporean, asked in our online survey to define the characteristics that she considers make a person "high class". In the wake of the social media debates on the subject of socioeconomic status that went viral last year in Singapore, many people found themselves asking the same question, though it's almost certain that their answers – for those who managed to settle upon one – were entirely different from this respondent's.

Social class is an eternal chimera: however egalitarian we may wish to believe ourselves, we all have a grab-bag of social cues that we use to rank our fellows. Whether it is an Hermès scarf, an aristocratic pedigree or an Ivy League education, we spend our lives constantly ranking those around us. Even more curiously, despite the fact that my own set of go-to class signifiers probably has little in common with yours, you will instantly understand what I mean when I say "high class".

However, while we all have heuristics for identifying others' social status, few of us would care to share them publicly, for fear of appearing shallow or prejudiced. This sensitivity surrounding the idea of exposing our guilty prejudices is a big part of what makes pinning down standard definitions of socioeconomic status so difficult.

Huge house somewhere inaccessible, on Nassim Hill for example. They have a separate house for their maids (plural). Head of household probably has swanky job in finance or they have family business in something boring such as steel or plastic or paper. They go to work everyday because wealth don't come cheap. Unless they come from old money, and I don't know what those people do daily.

- Female survey respondent, born 1992, defining high class

This is a particularly interesting question in Singapore, in light of the fact that the city state is a relatively young political entity. While societies like Europe and Northeast Asia have had the time to build up and tear down formal aristocracies, Singapore has not been in existence long enough to pass through this cycle. So what kind of hierarchies do ordinary Singaporeans perceive among their fellow citizens? Is class seen as being purely an affair of material prosperity? Or have Singaporeans assimilated traditions from the various cultures that contributed to and influenced Singapore society over time?

This is a particularly interesting question in Singapore, in light of the fact that the city state is a relatively young political entity. While societies like Europe and Northeast Asia have had the time to build up and tear down formal aristocracies, Singapore has not been in existence long enough to pass through this cycle. So what kind of hierarchies do ordinary Singaporeans perceive among their fellow citizens? Is class seen as being purely an affair of material prosperity? Or have Singaporeans assimilated traditions from the various cultures that contributed to and influenced Singapore society over time?

We were curious to find out, so we ran an anonymous online survey to find out more about ordinary Singaporeans' perspectives on social stratification. This opinion editorial is written based on the online survey that we recently conducted. You may download the report,

Cars, Condos and Cai Png by clicking on this

link or

the report image (above/left).

All about the money?

While the vast majority of the respondents described class purely in terms of material prosperity, 61% saw it as having a combination of behavioural and material factors, and for 3% of respondents it was purely a matter of actions and personal character. A small number of respondents took care to specify that the well-off can also be considered "low class" if they behave badly. Many respondents drew an implicit or explicit link between good character and financial wellbeing, suggesting that intelligence, generosity, charm and sincerity are likely to bring financial rewards.

At the other end of the scale, some saw wealth as being more the product of luck (often the luck of birth), a group that occasionally overlapped with those who saw wealth as being the cause of character flaws – notably a lack of empathy - among those who possess it. Similarly, in discussing "low class", respondents were divided on the relationship between poverty and personal character. Many felt sympathy for the poor, and a small number even praised their virtues – humility, an easy-going temperament and a willingness to work hard. Others argued that those that the economically and socially disadvantaged were largely to blame for their own predicament.

Has no private space, no hobbies, eat instant noodles everyday, have to borrow $ all the time, family argues about $ everyday, not having enough pocket $ for school, cannot hang out with friends because parents do not have enough $ to give me.

- Female survey respondent, born 1994, defining low class

The majority, however described class purely in terms of material factors. The most frequently-mentioned item was income and jobs, mentioned by a quarter of the respondents. High class status was marked by the ability to live off a passive income, or by managerial and professional jobs (doctor and lawyer were the two mentioned most often). By contrast, low status was marked by short term contracts and shift work. Interestingly relatively few respondents mentioned welfare. Housing came in second place, cited by 21% of participants: high class options were highly diverse – from 5-room housing board flats (HDBs) upwards – consensus suggested that low class housing implied anything smaller than a 2-room HDB, particularly if it was rented.

Flexible hours, owns a business and at least 1 investment property and come from an at least a well to do family background. That said, many fortunate people does not have the right attitude and empathy to ensure a inclusive society.

- Female survey respondent, born 1985, defining high class

The golf club vs. the kopitiam

Education came next, mentioned by 14% of participants. Interestingly, the vast majority of respondents mentioning education focused on the secondary level: having attended an independent school was a far more reliable class marker than having been to a high-ranked university. This was followed by car ownership, holiday destinations and language spoken. Interestingly, more people talked about cheap holidays as a signifier of a lower class than the inability to take holidays at all. Golf topped the list of high class leisure activities (followed by eating out, gyms and yoga, the arts, skiing and diving), while kopitiams (low-priced coffee stalls) occupied a similar place among low class recreations (in addition to karaoke, smoking, gambling and watching television). For many respondents, however, time to pursue hobbies was seen as the ultimate prize: while a few respondents described the well-off as hard-working, the term was used far more frequently in describing the lower classes. When it came to languages, English was seen as a sign of high class, particularly when spoken with a foreign accent. While some respondents mentioned code-switching between formal English and Singlish, only one mentioned the use of mother tongues. However, many more respondents mentioned eloquence in general than particular languages. Several specified a lack of fluency in any language, a tendency to use vulgar words, or loud speech in public places as a marker of low-class status.

Well educated, professional, own private property, car ownership and travel widely. He must show concerns for people and extends help whenever possible monetary or otherwise. Speak softly but with substance as wise man should be. Acknowledgeable and yet humble in dealing with difficult situation. Someone who can be relied on when needs arise.

- Male survey respondent, born 1952, defining high class

The Gucci gang: brands and class

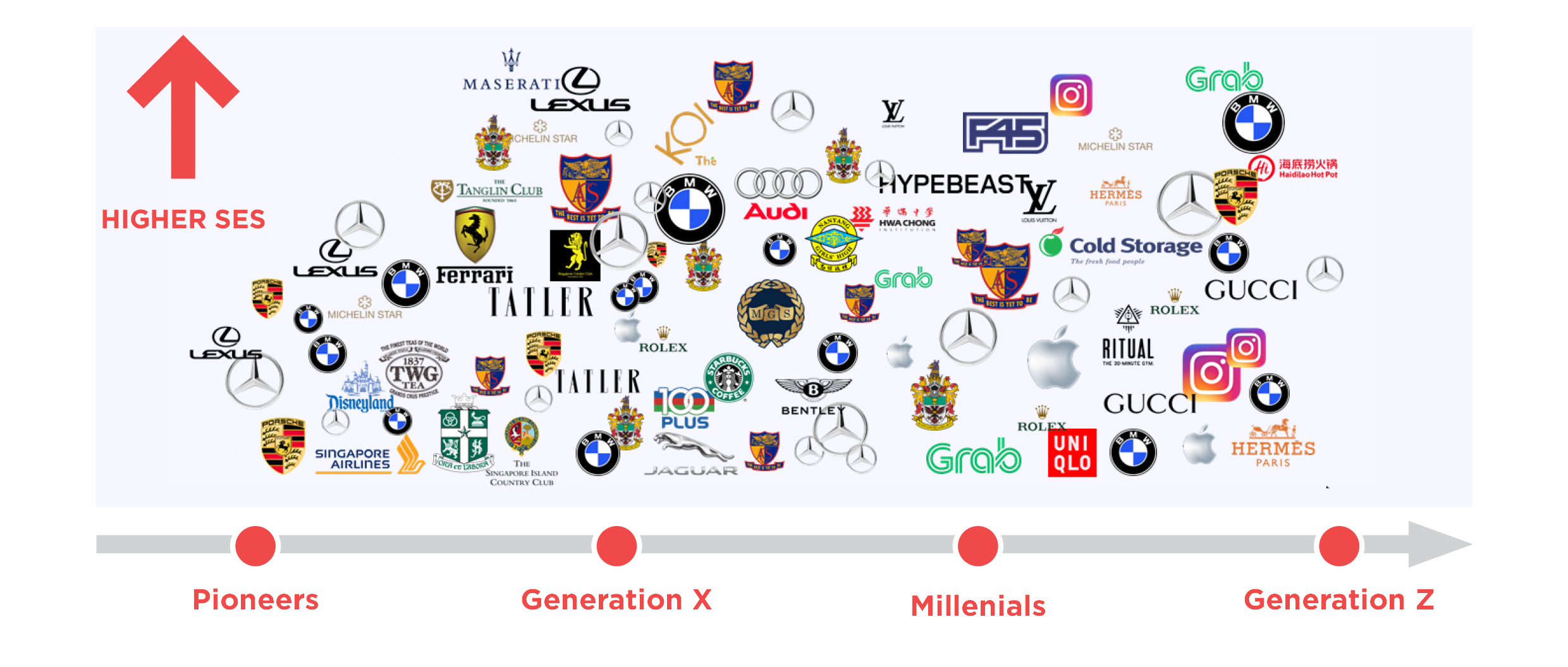

Figure 1 Brands associated with high class status

Figure 2 Brands associated with low class status

Many respondents also strongly associated specific brands with high class. It was also possible to track the mentions of brands across the generations. References to schools peaked among late generation X/early millennial respondents1 – unsurprising, given that they are both young enough to remember their own school days well, and old enough to have school-age children themselves. Among later millennials and generation Z, however, these brands tended to give way to smaller ticket items, such as social media bragging rights and gym memberships. Interestingly, some brands were associated with both high and low class: Grab, Uniqlo, Gucci and Louis Vuitton. The latter two cases would seem to imply that the parent companies were right to worry about the prevalence of counterfeits damaging their image, while the former are more a matter of individual perspective.

The Dog that Didn't Bark: Class and its Implications in Singapore

In making out the report we gradually came to divide class attitudes in Singapore into two main streams: Marxian and Confucian. For Marxian respondents, class is a concrete reflection of wealth: a fondness for golf or a degree from a foreign university are not inherently high class, but are seen as such because of the money required to acquire them. For these respondents, high class status is not necessarily a guarantee of good behaviour. For Confucians, on the other hand, class is determined entirely by behaviour: someone who behaves well remains high class, even in poverty, while no amount of money can make a badly-behaved individual high class. Some respondents attempted to reconcile the two perspectives, suggesting that material success tends to be the product of positive character traits, while others took the opposite stance, arguing that material prosperity is a source of arrogance and indifference among those who possess it.

This, in turn, leads on to one of the most interesting aspects of the data: the items that did not appear. While a majority of respondents had Marxian viewpoints on wealth, these should emphatically not be mistaken for Marxist viewpoints. No respondents – even among those who displayed the greatest resentment for class privilege – drew explicitly political conclusions from their observations. Inequality has been hitting the headlines recently in Singapore, but none of the respondents drew a link between this and their own personal perspectives on class. It is difficult to imagine a similar outcome in Europe or even in the US or China. This fact alone implies that while the Singapore government may be increasingly worried about the social consequences of inequality, it is simply not central to citizens' views of life in society to the same degree as it is elsewhere. While Singaporeans may like or dislike their own place on the social ladder, they do not necessarily see this as a problem inherent in the system itself.

[1] In delimiting generational age boundaries, we copied Pew, amalgamating the US categories “Boomers” and “the Silent Generation” into a single generation to better reflect Singapore perspectives. In the absence of a post-war prosperity-driven baby boom in Singapore we have labelled this super-generation “pioneers”, even though its boundaries exceed those conventionally assigned by the Singapore government. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/ft_19-01-17_generations_2019/

If you’re interested in reading such content, subscribe here.