Identity politics refer to political positions that are based on ethnicity, race, sexuality or religion. Politicians and civil society groups that base policies around one of these sectors look to protect that group's interests and privileges. This creates highly divided societies, fragments social cohesion and according to Stanford political scientist Francis Fukuyama, even undermines liberal democracies.

From South America to Asia, identity politics have bolstered populist regimes with autocratic tendencies, many of which commit serious human rights violations. A focus on white Americans helped US President Donald Trump win the 2016 US election while Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro ran a campaign focused on pro-gun, homophobic conservatives. Britain's decision to leave the European Union, meanwhile, revealed widespread concerns over migration policies and their supposed threat to British culture.

In Asia, identity politics takes various forms that include Islamism, anti-Chinese sentiment and right-wing Hindu nationalism. Speaking to Global-is-Asian, various experts pointed to how religion is in the spotlight as leaders and external groups look to protect members of their faith over others.

Asia is currently witnessing "a resurgence of religious-based politics" which is going to result in increased polarisation, observed Dr Mathew Mathews, Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. All kinds of powers are funding entities with a hard-line, religious agenda, "so we have to expect that [things] are going to be more and more tense," he continued.

To pinpoint the exact causes of religious radicalism, IPS and Singapore's Ministry of Home Affairs organised a Forum on Religion, Extremism and Identity Politics on 24 July 2019. Read about it here.

The case of political Islam

Islamic extremism is usually associated with terrorism but it also refers to the use of Islam in mobilising Muslim voters. Termed as political Islam, this is increasingly prevalent across countries with Muslim populations and bodes particularly dangerous consequences for Muslim-majority countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia.

In the secular democracy of Indonesia, the economic success of Chinese-Indonesians has created widespread resentment among the country's Muslims, according to various news reports and a 2017 survey carried out by the ISEAS-Yusuf Ishak Institute. That’s empowered hard-line Islamist organisations who exploit the situation to increase calls for wider implementation of Sharia law.

Political Islam not only pushes Muslims to the right, it also impinges on the basic citizenship rights of non-Muslims who feel like they lack a voice in a political system dominated by Islam, said Professor James Chin, Director of the Asia Institute at the University of Tasmania.

Malaysia's situation is especially "unique," Chin said. Throughout Southeast Asia, political Islam is mostly pushed by non-state actors but in Malaysia, "the government itself is also part of the problem."

As an example, he pointed to Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad's first tenure as premier in the 1980s. Back then, Mahathir was leading the UMNO-led government and trying to compete with Parti Islam Malaysia (PAS), its main challenger for the Malay-Muslim vote. For Muslim politicians in Malaysia, "the fastest way to get support among Muslim voters is to show that you are a champion of Islam," Chin explained. "It doesn't matter where you stand personally but in public, you have to set yourself as an Islamic champion."

Worried about losing the Malay electoral base to PAS, Mahathir recruited Anwar Ibrahim, "a well-known Islamic firebrand," into government — a move that "put Islam into the political system," Chin explained. Together with Anwar, Mahathir effectively institutionalised Islamic bureaucracy by creating Islamic universities, Islamic banking and by strengthening the Department of Islamic Development (JAKIM). "All these were basically institutions built by the government to promote Islam," Chin added.

As a result of the government institutionalising Islam into the bureaucracy, radicals were emboldened and increased calls to turn Malaysia into an Islamic state, Chin continued. The problem is compounded by the legal definition of a Malay, he added, pointing to how Malaysia's Constitution defines a Malay person as a Muslim.

Fast-forward to present day and whilst political Islam remains, Malaysian politics have done a complete about-face. Mahathir, now 94 years old and in his second tenure as PM, has turned against UMNO and is attempting to reform the system of Islamic bureaucracy that he created by pledging to review JAKIM and other Islamic entities. UMNO, now part of the opposition, is currently partnering with PAS in a historic alliance that would have been unthinkable in the 1980s to capture Malay voters and defeat Mahathir in the next election.

Methods of politicising identity

Parties in power have several options at their disposal to politicise identity. These include whisper campaigns — in which damaging rumours are spread about a target whilst the source of the rumours tries to stay anonymous — fake news, memes and coded political messaging known as dog whistles.

"Certain politicians are very good at what we might call whispering campaigns, they don't have to openly come out and say 'I belong to this religion' or not, but they know how to appeal to the base," said Chin. Trump, for instance, has never emphasised his Christian identity "but he knows how to reach out to this base," Chin observed, noting how the real-estate billionaire was "very good" at picking up Evangelist Christian votes.

In Malaysia, whisper campaigns are appearing that threaten to hurt Anwar Ibrahim's People's Justice Party. Rumours are spreading that Anwar is plotting against one of his deputies, Azmin Ali, as well as PM Mahathir — a development that could complicate Anwar's path to be Malaysia's next prime minister.

Dog whistle politics, meanwhile, are widely used by leaders such as Trump and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, whose ruling party espouses a right-wing brand of Hindu nationalism known as Hindutva. Modi's speeches commonly cite phrases from the Ramayana, an ancient Indian story of gods that subtly appeal to conservative Hindus. For example, Modi's use of a traditional battle cry — "Jai Shri Ram" — is generally interpreted as praise to Lord Rama, a revered Hindu deity. But to hard-line Hindus who oppose the country's minority Muslim population, the phrase also symbolises anti-Muslim violence. During acts of brutality committed by Indian Hindus against Indian Muslims, crowds now chant "Jai Shri Ram." As a result, Modi's use of the phrase in public rallies is now associated with violence against Muslims.

Memes and fake news as weapons

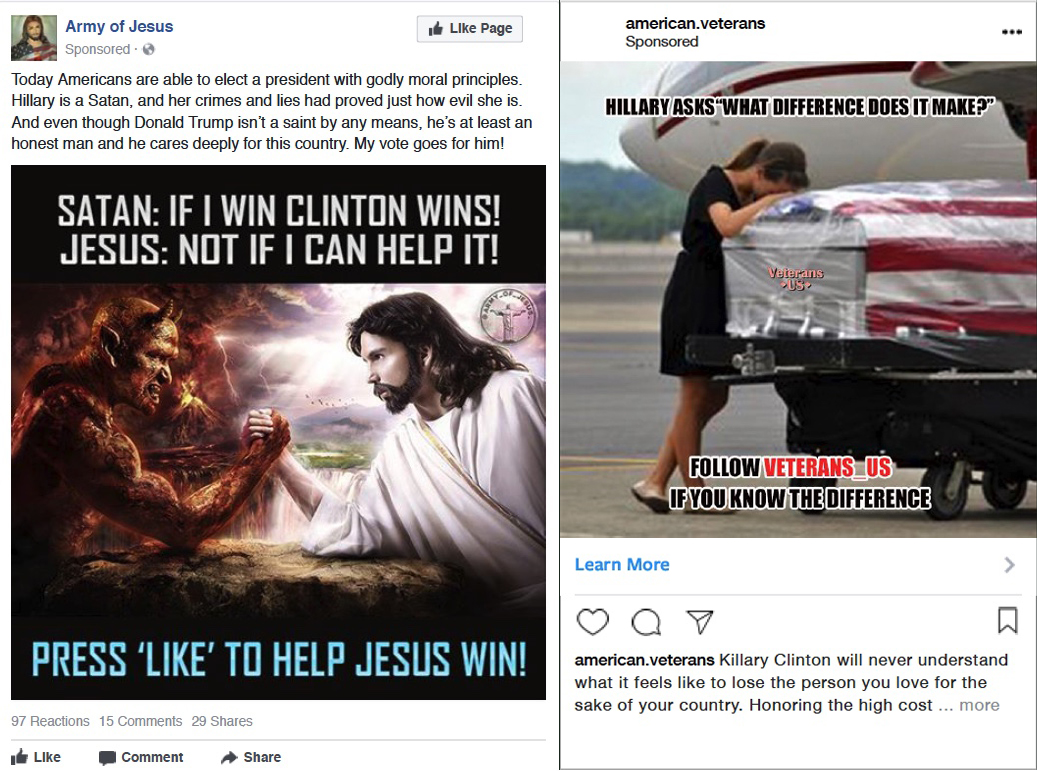

Examples of memes propagated by Russian actors during the 2016 US Presidential election: US House of Representatives Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence

In today's digital age, memes have emerged as one of the newer forms of exploiting identity for political gain. Traditionally a medium of humour, memes are increasingly used by millennials and Generation Z to approach serious issues, further complicating political discourse.

Governments are now paying attention. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), a specialised Pentagon unit, funded a study in 2011 on "Military Memetics," in which it argued that memes were crucial to fighting terrorists. That study was one of several research programmes into what DARPA called "neuro-cognitive warfare."

The DARPA study proposed that the global fight against terrorism was linked to a "war of ideas." A successful meme, it argued, should contain "information that propagates, has impact, and persists." Memes made by the US military would thus use humour to combat regions they deem to be at risk of radicalisation whilst subtly propagating US democratic values. According to media reports, some Democratic staffers are already creating memes to appeal to younger audiences.

Perhaps the most widely-used tool to politicise race and religion is digital disinformation via social media, or what's commonly referred to as "fake news."

Speaking to Global-is-Asian, James Crabtree, an Associate Professor in Practice at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, explained how Asia's relationship with social media has enabled pervasive disinformation and misinformation. Because platforms like Facebook and Twitter have rapidly become the dominant forms of communication within the region, that creates opportunities for foreign and domestic players to intentionally spread false information, he said.

Firstly, social media has greatly exacerbated existing ethnic and religious tensions across emerging Asia, whether it's Buddhists against Muslims in Myanmar or Hindus against Muslims in India, Crabtree explained. Moreover, many developing Asian countries possess "a relatively weak tradition of public service media". Countries such as India haven't had "the time or the money yet to develop the kind of high-quality, impartial public service media that you might get in France or Japan or the United States," he noted. That gives news shared on social media an advantage over traditional public media.

Finally, combine those factors with weak "fact-producing institutions," Crabtree continued. Government bodies such as national statistics or the court system are meant to produce facts that we don't question, but "emerging economies just aren't as good at that as South Korea or Norway in terms of producing information that people will agree with."

All these elements together "have created a real crisis where people don't trust the post-truth era, where people don't trust what they read online. That creates a new space for malign actors in a whisper campaign of all sorts."

To combat digital disinformation, governments must strengthen the credibility of fact-producing institutions, create high-quality public service media and create strict regulations for social media platforms, Crabtree argued.

The use of technology, specifically artificial intelligence, is currently being promoted as a way to flag false or hate speech online. But AI isn't enough because human intelligence is still needed, argued Francesco Mancini, Associate Dean and Associate Professor in Practice at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

"The reality is that artificial intelligence is still not enough" to pick up sensitive content such as the live stream of the Christchurch mosque attacks in March 2019, he said. Humans still need to verify what the AI has spotted, which could be in the form of various languages, images or code, he added.

Global-is-Asian will further explore the issues of memes on 22 November, 2019 in a forum titled: How Memetic Media is Changing the Nature of Public Conversations, as part of the inaugural Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy 2019 Festival of Ideas, Governance for the Future: Asia's Perspective

Photo: Rioters burn office furniture during the May 1998 riots of Indonesia, which was driven in part by racial resentment.

If you're interested in reading such content, subscribe here.