The new Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Mechanism is a game changer for water governance in the region, say Leong Ching and Louis Lebel from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. Here, they discuss crucial components of an alternative architecture to regulate large-scale infrastructure projects.

A 4,350km-long river may seem like an empirical fact of nature, but changing its name can sometimes remake its character. The Lancang-Mekong River flows through six countries: China, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. It also has two names: Lancang' (澜沧) within China and Mekong' outside of China.

Traditionally, water governance of the Lancang-Mekong has been fragmented and contentious, in part due to the prevalence of powerful vested interests and lack of transparency in decision-making, but also because of political sensitivities in dealing with transboundary drivers and consequences.

China's growing role in the region

The launch of the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Mechanism (LMCM) in 2015 is emerging as a significant alternative to the Mekong River Commission (MRC) and the Asian Development Bank's (ADB) Greater Mekong Subregion group. China and Myanmar are involved in the MRC because it is not water-centric, while in the case of the ADB, there is a sizable investment opportunity. As part of the LMCM, China has pledged US$1.5 billion in preferential loans and a US$10 billion credit line.

Calling the river Lancang-Mekong' rather than mere Mekong' asserts a new regime upstream. It is not only bringing new actors to the table, but also remaking the table altogether. In this, we do not argue for a new architecture so much as the addition of an alternative one an architecture that shadows the current institutions, but will rise in both importance and impact in the coming two decades.

This alternative architecture one that is less dominated by conventional state apparatus and international environmental agreements is emerging to promote and regulate an array of large-scale water, energy and transport projects with huge implications for the well-being of the region's inhabitants.

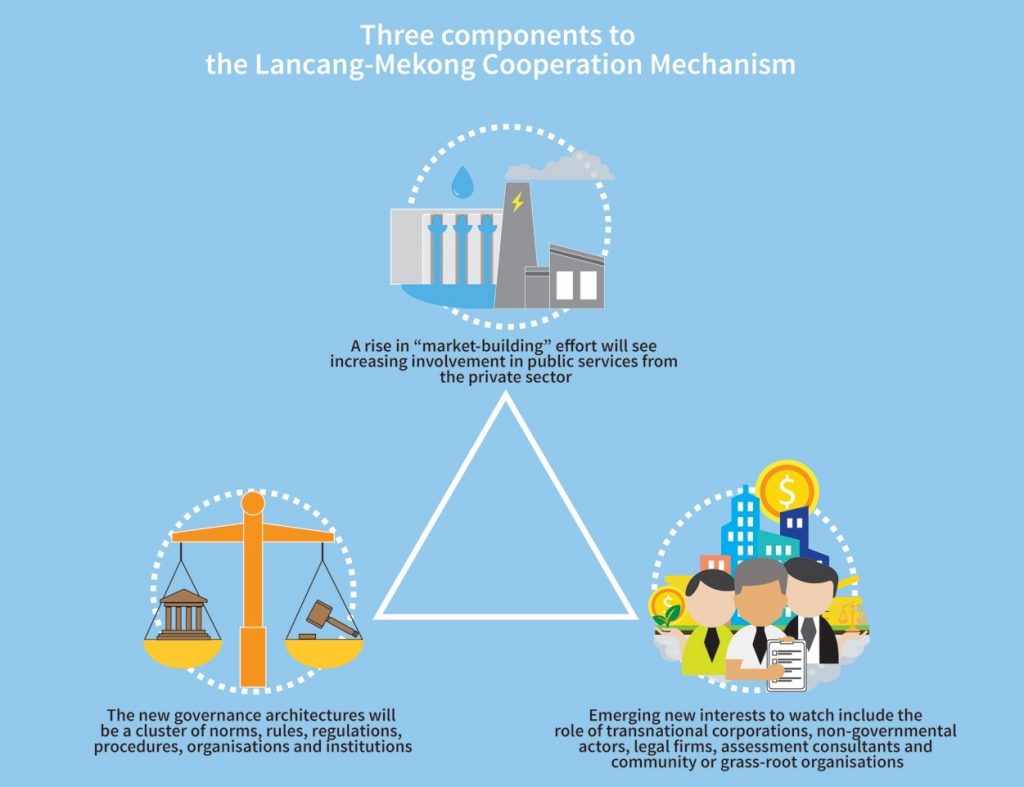

We see three essential components of this new structure.

Increasing market-building efforts as part of this alternative architecture

First, a rise in market-building efforts, with the private sector increasingly involved in the delivery, planning and even financing of public services including energy and water infrastructure. Even as state-enterprises remain extremely important in these sectors and will continue to shape market institutions, we argue that such market-building efforts will continue to intensify, transforming the ecological and economic landscape of the region.

Developing new governance architectures and regulatory regimes

Second, these efforts will be guided by and themselves influence new emerging governance architectures and regulatory regimes. Governance architecture refers to a complex or cluster of norms, rules, regulations, procedures, organisations and institutions governing a problem domain.

In this new architecture, investment by Chinese state enterprises, private firms and banks as well as commercial banks from Thailand, Vietnam and other countries will likely expand even further. This shift in financing sources has already raised concerns over the adequacy of investment standards and the accountability of project developers including recipient country governments for long-term impacts.

Dominant narratives of such market-making efforts have focused on governance goals such as efficiency, effectiveness and high performance, but often neglected issues of fairness and environmental justice. Policy studies scholars are concerned about the diversity of forms and governance models, while scholars of international relations focus on the power relations between different states, including the role of regional and global hegemons.

What is missing is a meso-level analysis of the institutions that regulate the flow of capital, the forms of financing and hence the distribution of risks, burdens and benefits of many large-scale projects. We need to therefore engage more deeply with both bodies of work as well as emerging work on deliberation at multiple scales, regulation of infrastructure financing and legal pluralism.

We need to construct frameworks for understanding regulatory forms, including legitimacy models that have been employed in the governance of the Mekong. These include extant forces that continue to be important such as bureaucratic government incentives and contestation between different state interests.

Recognising the role of multiple actors

Last, we think it is important to look at new emerging interests such as the role of transnational corporations, non-governmental actors, legal firms and assessment consultants as well as the slow rise of powerful community or grassroot organisations.

An examination of the recent history of governance in the Mekong region reveals three broad phases: the new public management' model in the early 1990s, the regulatory state' in the early 2000s and finally, new emerging communitarian' models of legitimacy. We argue that the last could already be serving as an alternative to current models being used in the governance of the Mekong.

It has therefore become urgent and critical to understand how changes in the governance architecture for water and energy in the Mekong region have influenced decision-making on large-scale infrastructure projects. We also need to develop and explore the implications of alternative architectures with stakeholders. This includes their potential performance under different assumptions about the future in relation to water, energy and food security, for instance.

Looking ahead, we need to pay attention to not just states and their interests, environments and communities, but also the role of money and corporate law. We need to recognise that corporations, lending agencies, legal firms and private sector financing institutions are important components of an alternative architecture.