TRIPARTISM

Tripartism and Industrial Relations

scroll to explore

Throughout the years, tripartism and the relationship between the tripartite partners have been tested through several economic crises and events. One example is how the NWC responded to the 1985 economic crisis.

High-Wage Policy and 1985 Economic Crisis

Singapore is known for its open and dynamic economy. The country’s economic success has been driven by a state-centric approach to governance that emphasises regulatory transparency, effective and timely policy interventions and a robust economic infrastructure.

In the formative years of the National Wages Council (NWC) from 1972 to 1978, wage increases of 6% to 9% were recommended each year, except in 1974 when the NWC recommended a $40 + 6% general net wage increase, to help workers earning lower wages cope with high global fuel and food price inflation.

| Year | Recommended wage adjustment |

|---|---|

| 1972 | 8% increase |

| 1973 | 9% increase |

| 1974 | $40 + 6% increase |

| 1975 | 6% increase |

| 1976 | 7% increase |

| 1977 | 6% increase |

| 1978 | $12 + 6% increase |

| 1979 | $32 + 5% increase |

| 1980 | $32 + 7.5% increase |

| 1981 | $32 + 6 to 10% increase (with an additional 3% for ‘above average performers’) |

| 1982 | Productivity-based adjustment according to 3-year restructuring wage policy |

| 1983 | $10 + 2 to 6% |

| 1984 | $27 + 4 to 8% |

| 1985 | 3 to 7% increase |

| 1986 (Apr) | Wage standstill |

| 1986 (Dec) | Severe wage restraint |

| 1987 | Severe wage restraint |

The NWC was able to recommend substantial wage increases from 1979 to 1982. This was commonly referred to as Singapore’s ‘high-wage policy’.

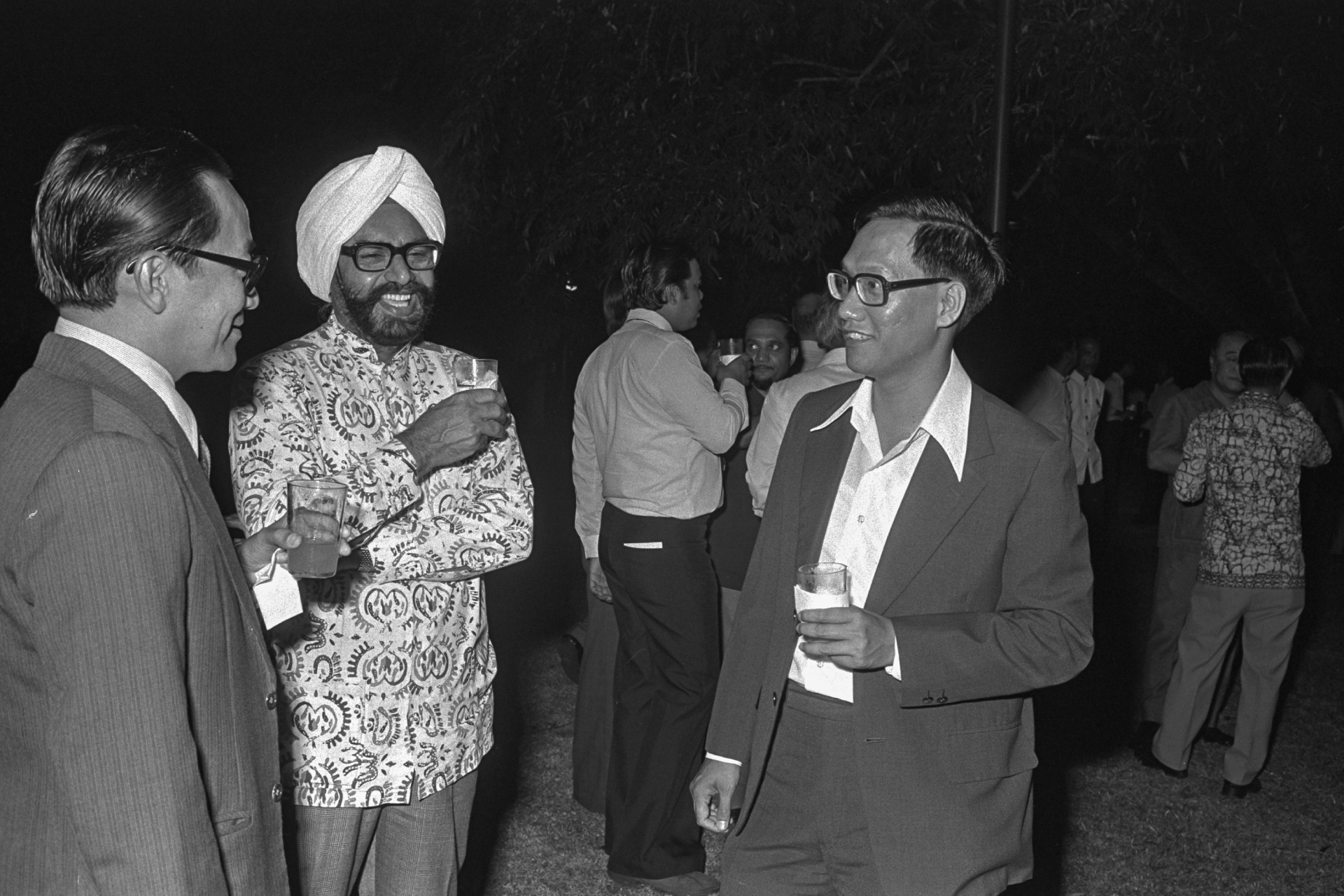

Member of Parliament for Bukit Merah Lim Chee Onn (right) and Chairman of National Wages Council (NWC) Professor Lim Chong Yah (left) at dinner for delegates of the Second Asian Labour Summit hosted by Minister for Labour Ong Pang Boon at Istana, 1979.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

In a jointly signed letter to Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew in June 1979, NWC Chairman Professor Lim Chong Yah, alongside Stephen Lee (President of the National Employers’ Council) and Devan Nair (President of National Trades Union Congress), highlighted the urgent need to restructure the economy by allowing wages to rise. The tripartite partners also emphasised the need for workers from low-wage and labour-intensive areas of employment to be trained for more productive and high-wage employment in other areas.

The tripartite partners pointed out in their joint letter:

“Unless this is done, we will be caught in the trap of low wage increases to support labour-intensive, low-skill industries and services. Low wage increases will enable such industries to expand further and use even more labour unproductively. Moreover, new and better industries will be hampered by labour shortages. Productivity will suffer and consequently our growth in per capita income will be less than our potential.”

The overall result was a 20% wage increase per year for three years from 1979 to 1981, with wage costs rising twice as fast as productivity.

Accompanying this new wage increase was an increase in the Central Provident Fund (CPF) contribution rates for both employers and employees to 25%. This meant that the take-home wages of workers were reduced despite their gross remunerations rising. A Skills Development Fund (SDF) was also introduced, which required employers to pay a compulsory levy of 4% of the 20% wage increase per year for their workers earning less than $750 a month. The SFD aimed to help low-wage workers to move into more capital-intensive industries for high-wage employment.

By 1985, however, Singapore had slid into a recession. A rapid decline in global demand, particularly in the United States, posed threats to a trade-dependent Singapore. Singapore was caught unaware by the 1985 crisis. The country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was initially projected to grow by 5%, but instead shrank by 1.5% when the crisis struck.

Second Deputy Prime Minister and National Trades Union Congress Secretary-General Ong Teng Cheong visiting Great Malaysia Textile Manufacturing Factory in Tanglin Halt Road, 1987.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

The reductions in CPF contribution rates as well as wage freezes were a form of implicit subsidy to firms’ wage costs, to encourage them to maintain their headcounts and business operations.

Second Deputy Prime Minister Ong Teng Cheong chairing a discussion with 200 union leaders on recent proposals to overcome the recession at the Singapore Conference Hall, 1986.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

200 union leaders attending a discussion by Second Deputy Prime Minister Ong Teng Cheong on recent proposals to overcome the recession at the Singapore Conference Hall, 1986.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Flexible Wage System (FWS)

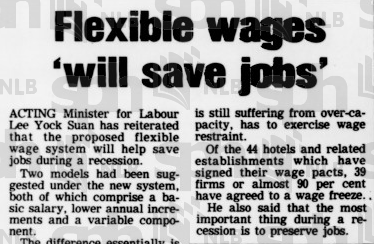

Following the 1985 recession, reducing wage rigidity in Singapore became a priority for the NWC. The NWC recommended a “wage standstill” in April 1986 and later revised its guidelines to recommend “severe wage restraint” in December. The 1987 guidelines later repeated the call for severe wage restraint.

In addition to these short-term responses, policymakers realised the need to introduce greater flexibility in Singapore’s wage structure. A more flexible wage structure was envisaged to allow businesses to adjust their wage bills according to business conditions. The NWC began encouraging wage reform in favour of flexible wages, and shifted fully to qualitative wage recommendations, starting with its 1988 wage guidelines. Following the 1986 report of the Economic Committee, the government introduced the Flexible Wage System (FWS). Fixed components in the FWS would provide employees with stability, while variable components would allow employers to respond promptly to changes in the economy.

Ong Yen Her, Divisional Director for Labour Relations and Workplaces, MOM (1985 to 2012), recalls there was a push for more wage flexibility after the 1985 recession. There was a sense that the NWC’s quantitative wage guidelines were too blunt to be applied nationally across all companies. Eventually, it was decided that the NWC would continue to issue annual wage guidelines but would shift to qualitative ones instead.

Ong Yen Her, Divisional Director for Labour Relations and Workplaces, MOM (1985 to 2012), recalls there was a push for more wage flexibility after the 1985 recession. There was a sense that the NWC’s quantitative wage guidelines were too blunt to be applied nationally across all companies. Eventually, it was decided that the NWC would continue to issue annual wage guidelines but would shift to qualitative ones instead.

Lim Boon Heng, Secretary-General of the NTUC (1993 to 2006) and Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office (2001 to 2011), explains that qualitative wage guidelines are used to establish a common understanding among tripartite partners of Singapore’s economic situation while giving them significant latitude in wage negotiations and wage setting:

When employers are able to reduce their wage bills in challenging economic conditions by adjusting the variable wage components, they are less likely to resort to retrenchments to maintain business competitiveness. In the absence of automatic economic stabilisers like unemployment benefits, large job losses in the middle of an economic crisis can lead to a slump in aggregate demand that exacerbates the downturn. Businesses that can retain their experienced employees in a downturn would also be able to respond faster to the eventual recovery.

Introducing flexibility into the wage system was important because the Singapore government had become increasingly reluctant to use the adjustment of CPF contribution rates as a policy tool for crisis response. Reducing CPF contribution rates affects all waged employees regardless of employment situation. The negative effects are felt both in the short term (e.g. reducing the ability of households to cover their mortgage payments with their CPF funds) and in the long term (e.g. the diminution of future retirement payments as a result of smaller present contributions). In fact, the NTUC itself warned employers in 1991 that they needed to implement flexible wages because the unions would no longer support such cuts to CPF contributions as cost reduction measures.

Robert Yap, President of SNEF (2014 to 2024), explains that the FWS can in fact offer better wage stability for employees, especially during times of economic downturn when employers can trim wage costs by adjusting the “shock absorber” of the FWS:

Besides improving the ability of businesses to respond to crises, policymakers believed that variable wages tied to business performance could incentivise employees to improve their productivity. Since 1988, both the NWC and the government have been regularly encouraging employers to adopt the FWS by increasing the variable components of their employees’ wages.

1997 Asian Financial Crisis

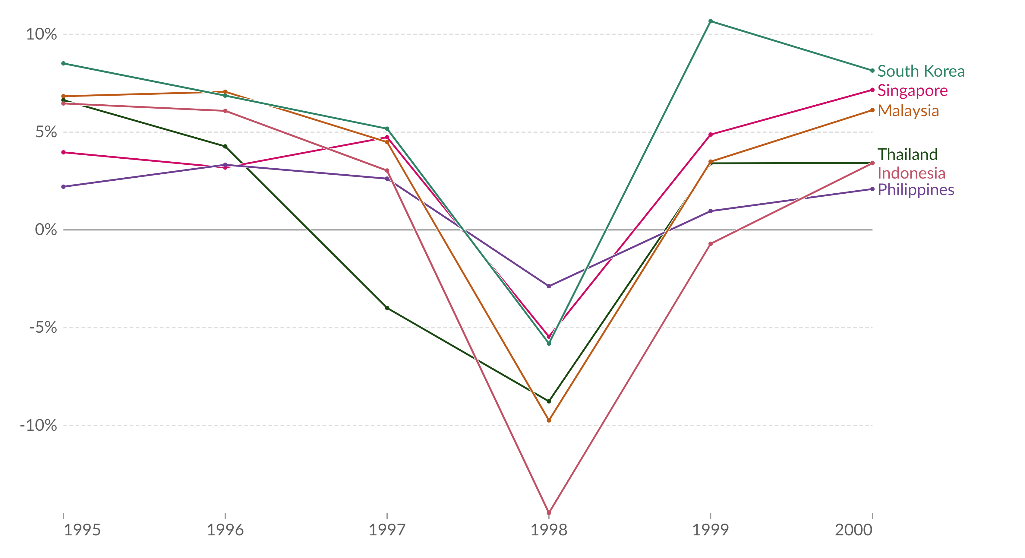

The NWC wage guidelines also enabled Singapore to navigate future economic crises with rapid wage adjustments, as was the case in the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

The 1997-1998 Asian financial crisis originated in Thailand in mid-1997 and quickly spread to other economies in the region. Regional currencies fell precipitously against the US Dollar (with most depreciating between 30% to 80%) and stock markets slumped as foreign lenders and investors panicked. Singapore dipped into recession in 1998.

Since the Singapore Dollar depreciated less against the US Dollar (by less than 20%) compared to other regional currencies, our exports became less price competitive. Disinclined to intervene in the foreign exchange market to further depreciate the Singapore Dollar as the crisis became protracted, the government opted instead for cost-cutting measures to restore competitiveness.

Annual GDP per capita growth of select Asian countries (%),

1995-2000

Source: Roser, Max, Pablo Arriagada, Joe Hasell, Hannah Ritchie,

and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina. 2023. Economic Growth. Our World in Data.

As part of the cost reduction package that included wide ranging cuts to government fees and charges, the employer’s contribution to CPF was reduced from 20% to 10%. This was similar to the government’s response to the 1985 recession, when the employer’s contribution rate was cut from 25% to 10% (subsequently partially restored to 20%). In its revised wage guidelines issued after the economic situation deteriorated, the NWC recommended wage reductions of between 5% to 8%. These guidelines went further than those issued in the aftermath of the 1985 recession, which only urged “wage restraint.”

The Singapore government set an example by slashing civil service salaries by up to 5% and freezing the salaries of ministers and senior civil servants. The combined effect of this cost reduction package was to “plunge” Singapore’s unit labour costs back to 1992/1993 levels.

The NWC’s wage guidelines helped Singapore recover strongly from its second recession by quickly restoring export cost competitiveness. The country’s economy subsequently grew by 9% in 2000.

COVID-19 Pandemic

A COVID-19 nasal rapid self-test kit indicating a positive result

In more recent times, the NWC also played an instrumental role in dealing with the economic downturn caused by the COVID 19 pandemic. As retrenchments and unemployment in Singapore surged in the first half of 2020, the NWC urged employers to cut non-wage costs, adhere to the guidelines set forth by the Tripartite Advisory on Managing Excess Manpower, and tap on the government’s wage offset schemes, such as the Jobs Support Scheme.

It recognised that struggling employers could cut wages with management leading by example, but shielded low-wage employees by recommending a wage freeze or even a built-in increase of up to $50.

Changi Airport at the height of COVID-19 pandemic, 2020.

In a rare move reflecting the severity of the crisis, the council issued supplementary guidelines in October 2020, urging employers to minimise retrenchments by imposing wage cuts if necessary, within the framework of the FWS. For low-wage employees, the NWC recommended a wage freeze and cautioned against cutting basic monthly wages to below $1,400.

A no-dining sign at a hawker centre

Singapore saw its sharpest fall in total employment in the first half of 2020. By the second half of the year, the labour market picked up, and unemployment and retrenchments eased. By October 2021, the NWC was calling on recovering businesses to restore or increase wages. The NWC also called for a wage increase of 4.5% to 7.5% of gross wages, or $70 to $90, whichever was higher, to enable the wages of low-wage employees to grow faster than the median wage.