TRIPARTISM

Tripartism in The Early Years

scroll to explore

A Straits Settlement

Without Formal Labour Unions

Before 1942

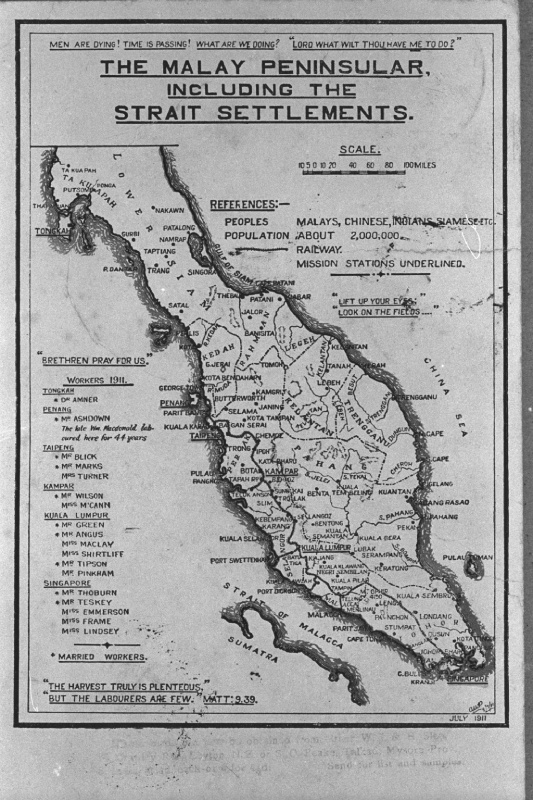

Singapore, together with Malacca and Penang, formed the Straits Settlements till after World War II. British intervention in the Malay peninsula saw an expansion of tin mining and rubber plantations to export raw materials to Britain and then onward to the rest of the world. The increase in such labour-intensive activities triggered a surge in demand for labourers to work in mines, plantations and construction sites.

Chinese coolies, c. 1880s, 1880.

Credit: Morgan Betty Bassett Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

The mid-19th century also saw an increase in labour costs, forcing the government to rely heavily on convict labour for public development works. A large part of this workforce was made up of Indian prisoners.

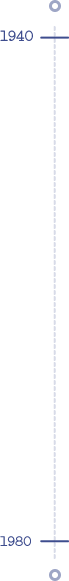

Singapore river, 1830.

Credit: Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

The British tended to hire Malays for the police force, armed forces and other unskilled roles in the public service, and by 1961 more than 50% of Malays relied on the public sector for employment.

The incoming surge of workers included a large influx of Chinese immigrants who were driven by poverty in China to seek a better life in Singapore.

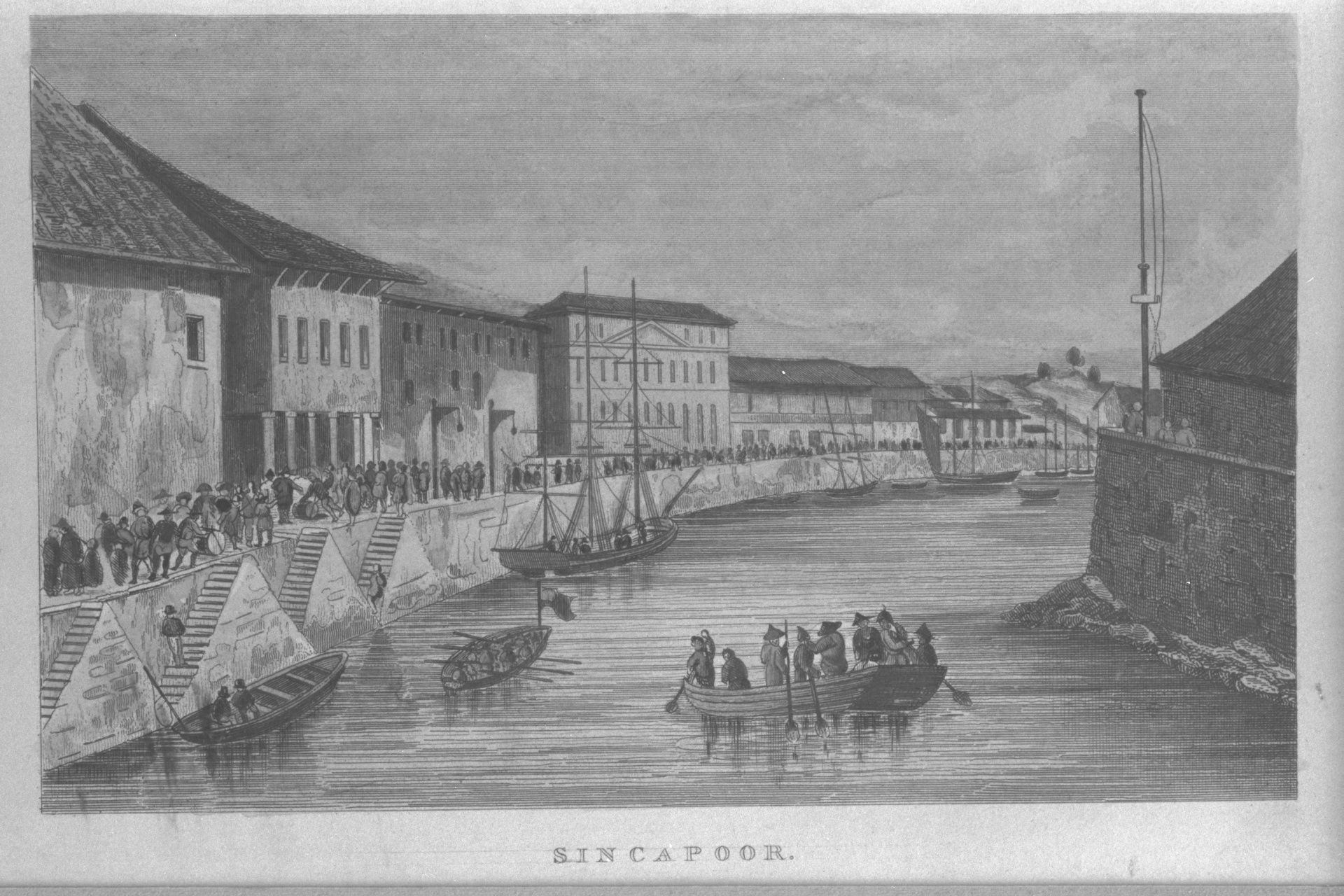

Ship discharging coals, Singapore, c.1910.

Credit: Andrew Tan Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

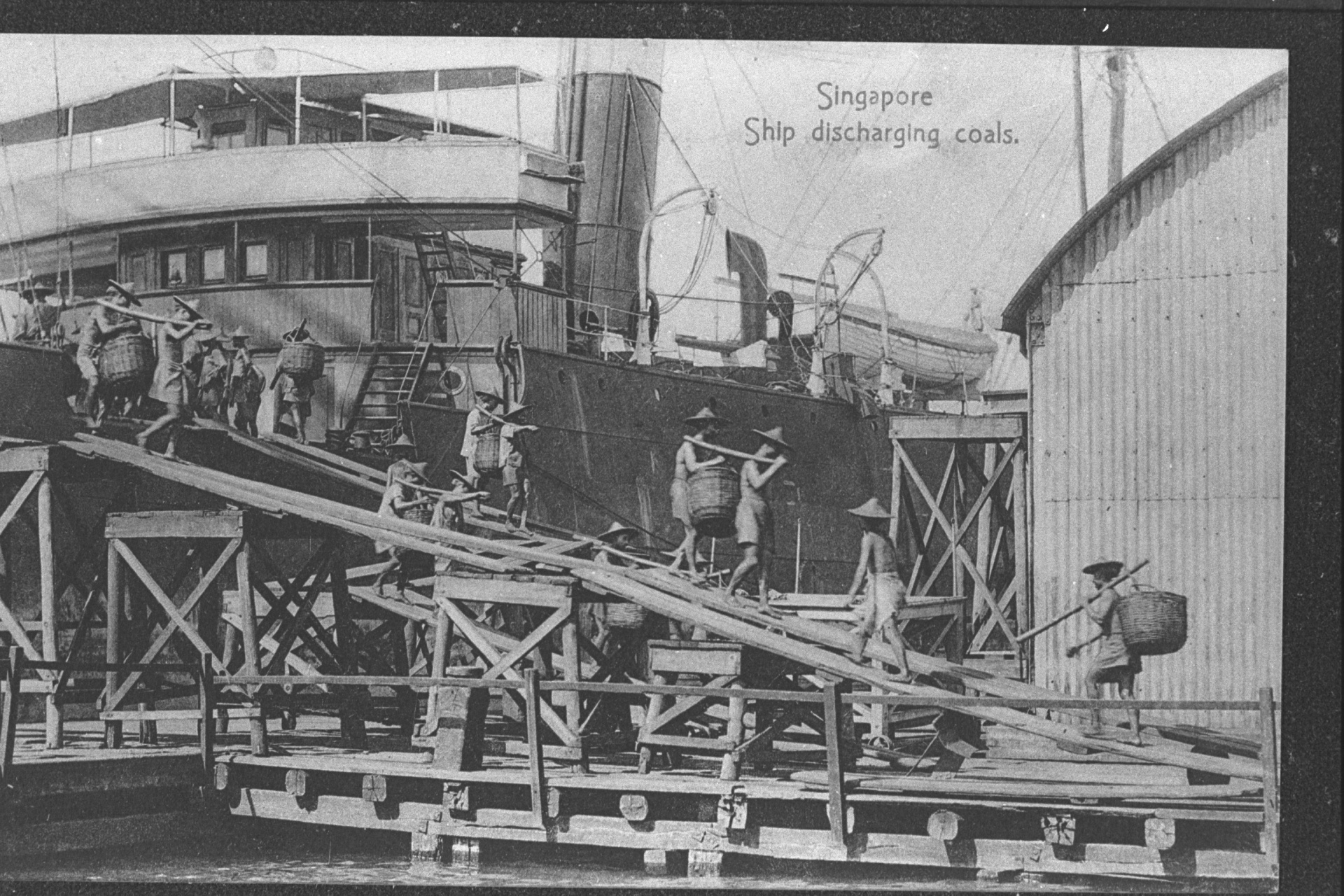

During these early years, there were no organised labour unions to represent workers in Singapore. Workers’ welfare was heavily dependent on the goodwill of employers. However, by 1877, the frequent ill-treatment of Chinese workers led to the establishment of a Chinese Protectorate in Singapore.

The Chinese Protectorate building at Havelock Road, Singapore, 1911.

Credit: Arshak C Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

One of the main functions of the Protectorate was to prevent new Chinese immigrants from approaching secret societies for help and encourage them to turn to the Protectorate for direct assistance instead. The numerous Chinese trade guilds or hongs which were already involved in controlling the influx of hard labourers also assumed the informal role of negotiator between employers and workers.

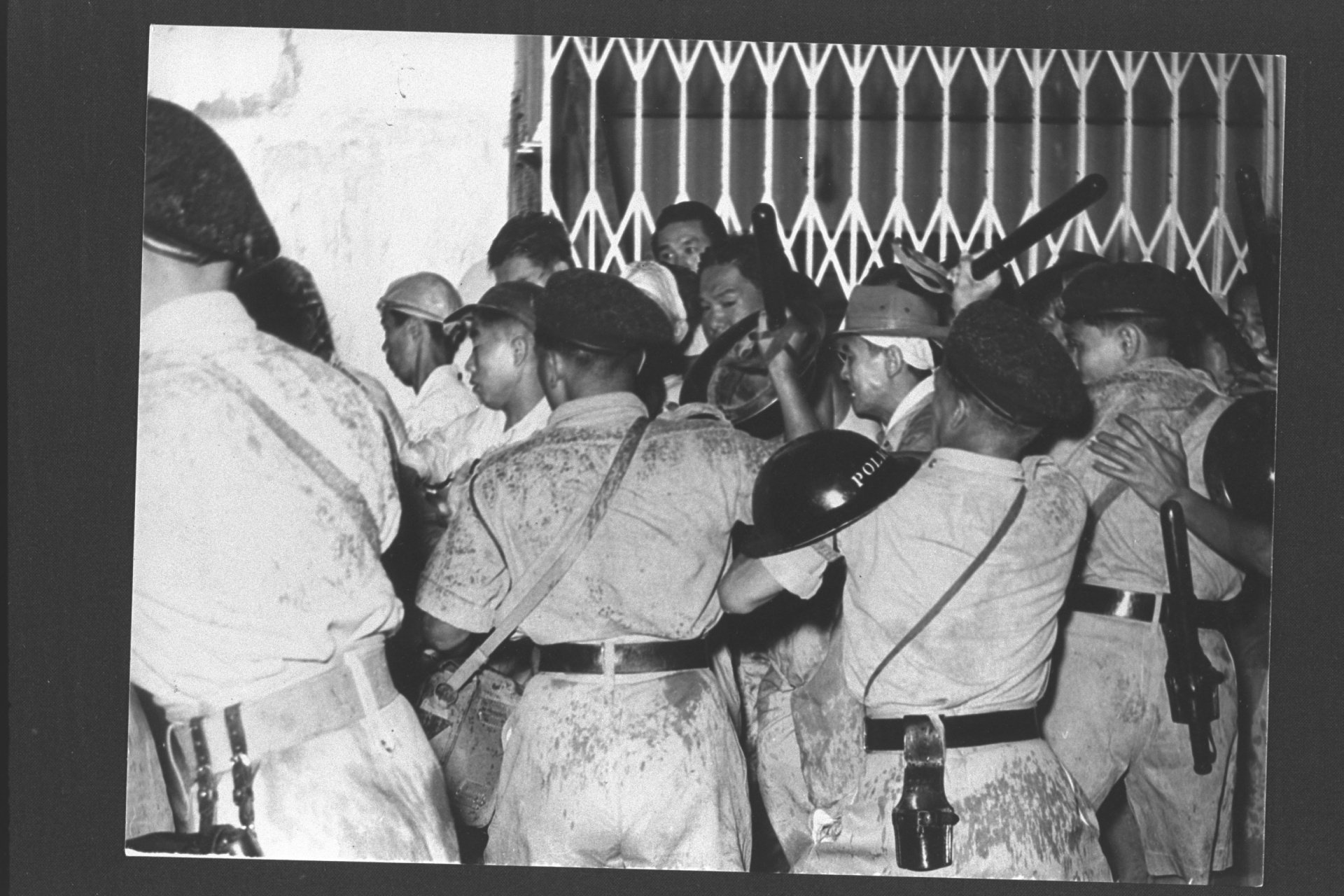

Police controlling riots, 1965.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

In the 1920s, communist ideology from China reached Singapore through the arrival of new migrant labourers.

Through the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM), the communists began to promote their anti-colonial ideology and organised several pan-Malaya strikes, calling for higher wages for Chinese workers. This paved the way for them to stir anti-colonial sentiments in future.

Following the Great Depression of 1929, the British administration encouraged manufacturers, mostly British, to form the Singapore Manufacturers’ Association, with the aim of promoting local industries.

Surrounded by anti-colonialist sentiments and increasing signs of labour unrest, new legislation was introduced in the Straits Settlements in 1939 to declare trade unions lawful and require their registration.

Map of the Malaya Peninsula,

including the Straits Settlements, July 1911.

Credit: Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of

National Archives of Singapore

Between 1940 and 1941, the Straits Settlements Legislative Council formally passed and implemented the Industrial Courts Ordinance and the Trade Unions Ordinance. However, there were no attempted registrations of trade unions, likely due to the onset of World War II and staff shortages.

World War II

1942-1945

Prior to the outbreak of World War II, the CPM established an umbrella Trade Union Federation to consolidate the support of local labour unions and organise the labour force against the Japanese invasion. However, most union activities either ceased or went underground during the Japanese Occupation from February 1942 to September 1945.

Once the Japanese forces had surrendered to the British, Singapore came under the British Military’s administrative control until a civilian government took over in April 1946.

Arrival of Japanese Delegation led by General Itagaki Seishiro, escorted by allied military officers, to City Hall to sign the Instruments of Surrender, 1945.

Credit: Dr Khoo Boo Chai Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Proliferation of Labour

Unions Worried Employers

Rattan factory, 1948.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

While the British regime had worked well with leading Chinese businessmen, often appointing them to the Legislative Council and the Chinese Advisory Board, the rights and treatment of labourers were still reliant on the goodwill of their employers.

At the end of World War II, working conditions remained poor amid widespread unemployment and high prices of food and other necessities. Workers often worked up to 12–14 hours a day and were given only two days off work every year during the Lunar New Year.

1946-1949

RESURFACING OF UNION LINKED TO COMMUNIST PARTY OF MALAYA

After the war, the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) resumed its anti-colonial agenda and activities. Blurring the lines between championing workers’ rights and anti-colonial sentiments, the CPM established a General Labour Union in Singapore and promoted it vigorously. This struck a chord with many Chinese-speaking industrial workers who saw the union as a solution to their poor working conditions.

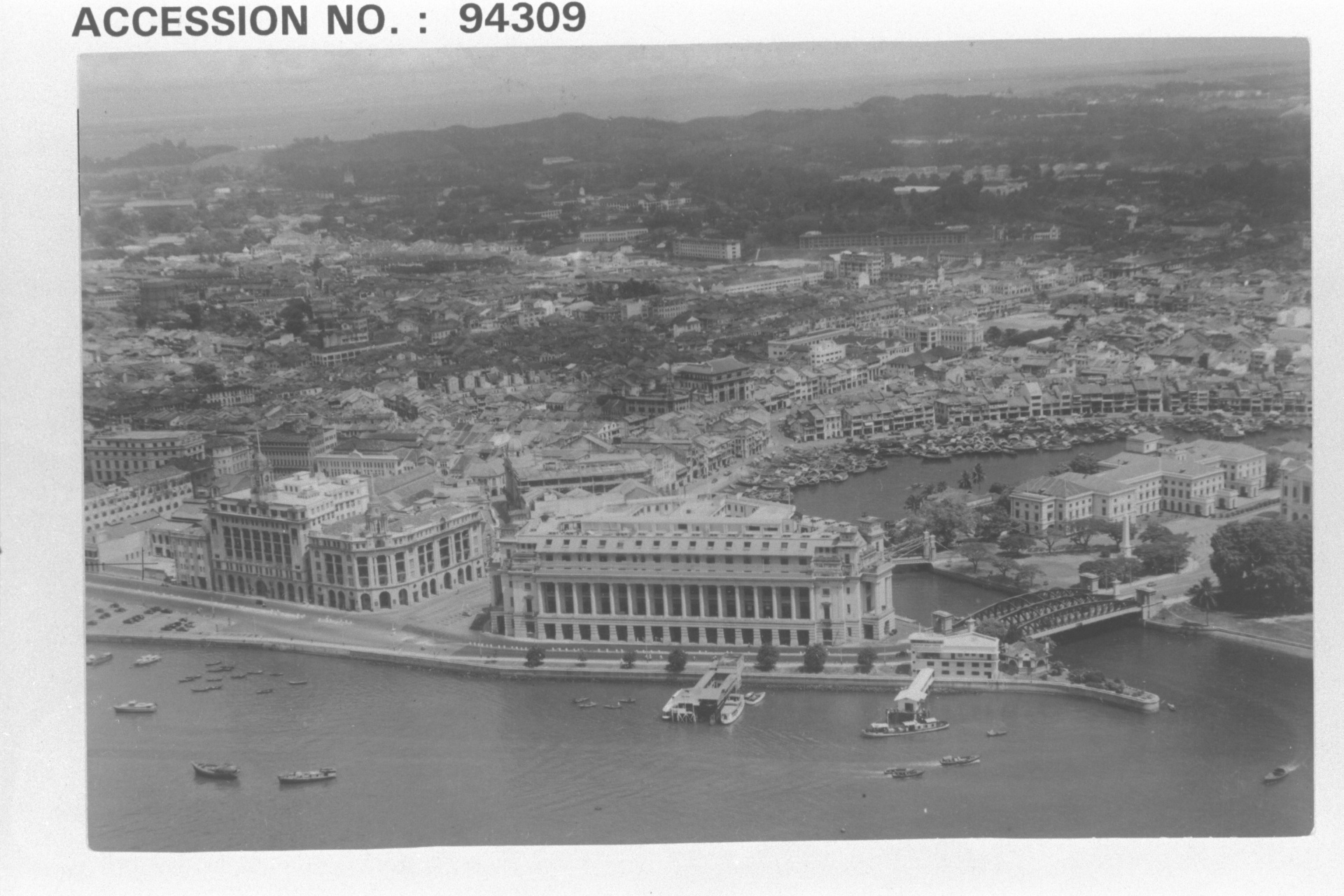

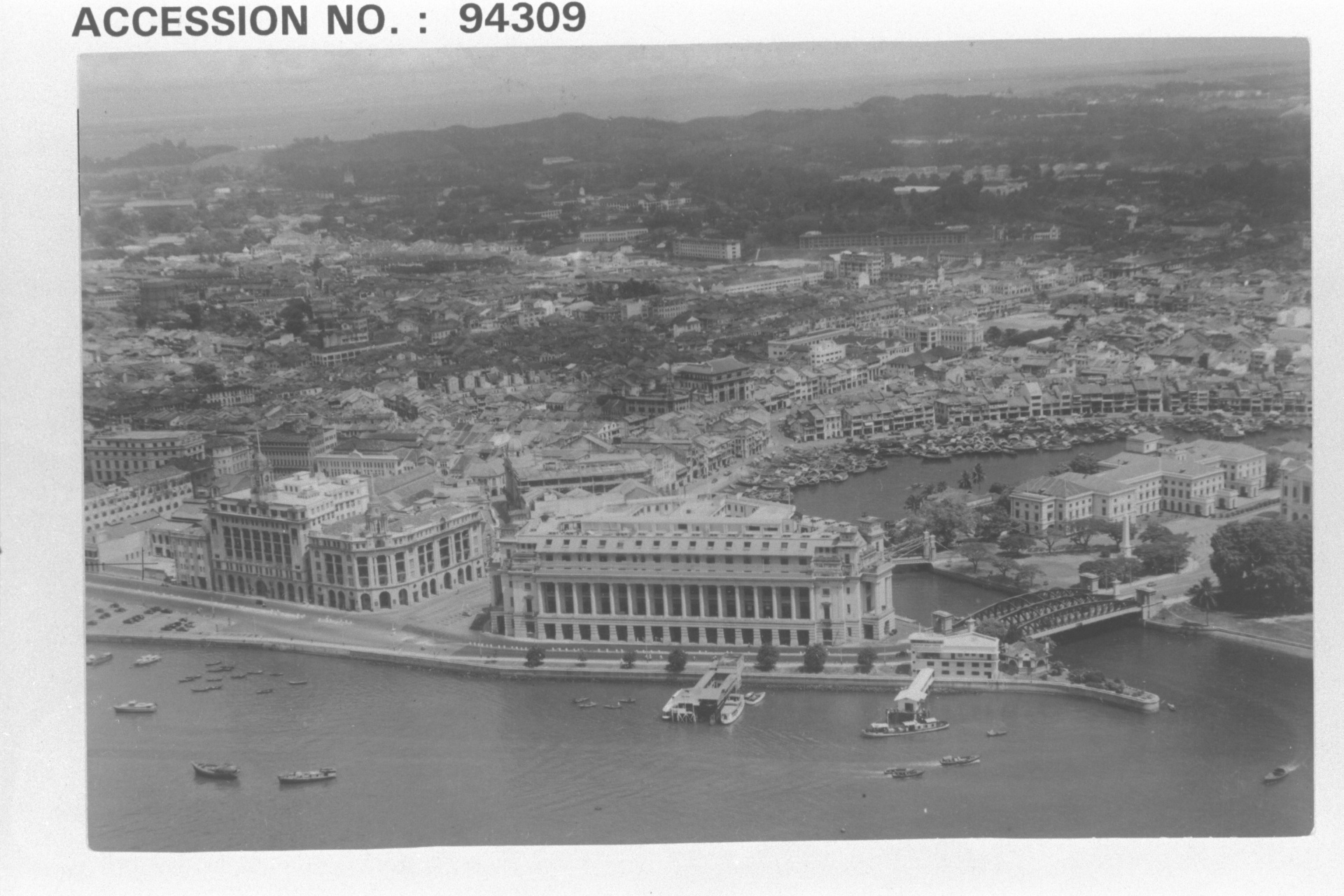

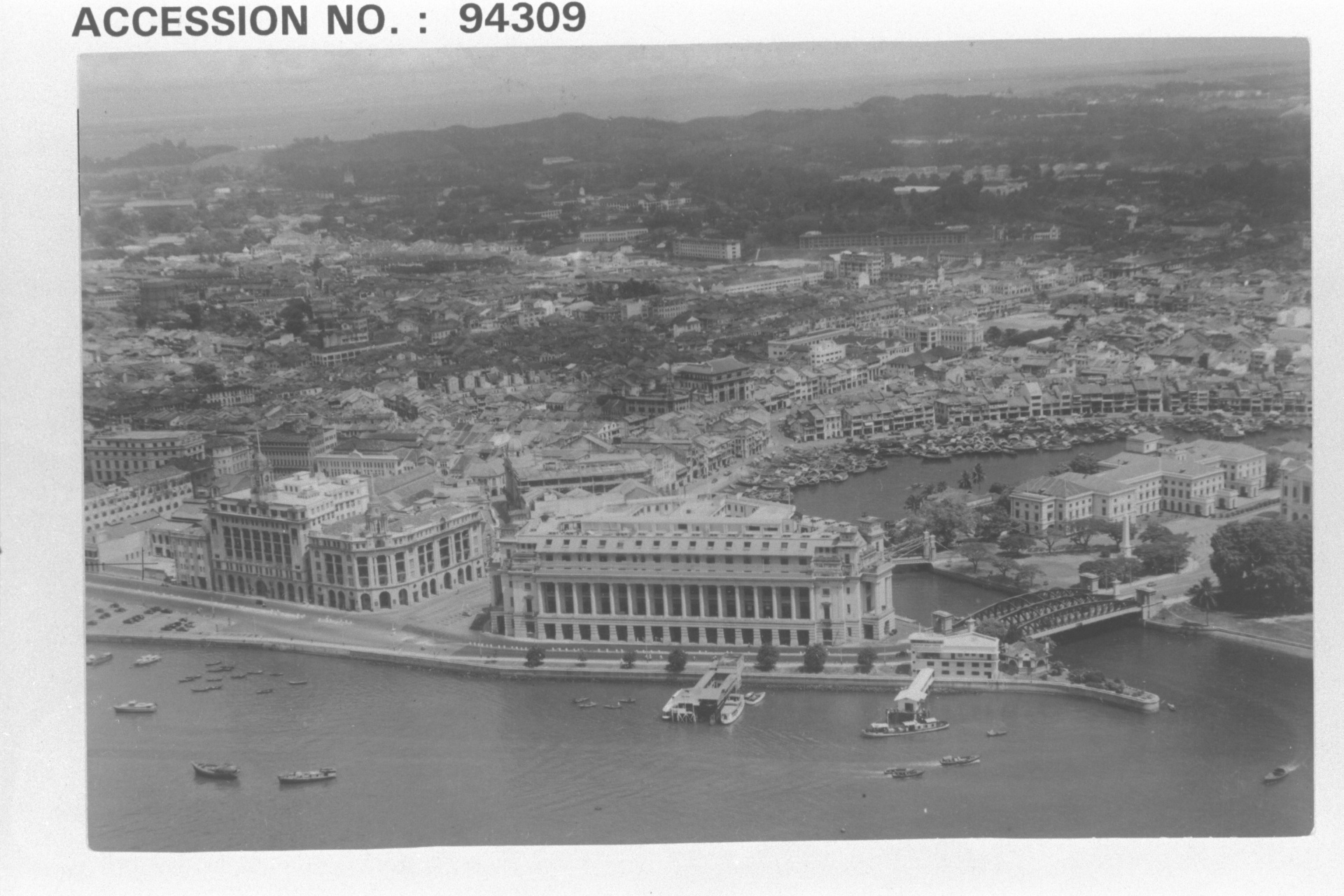

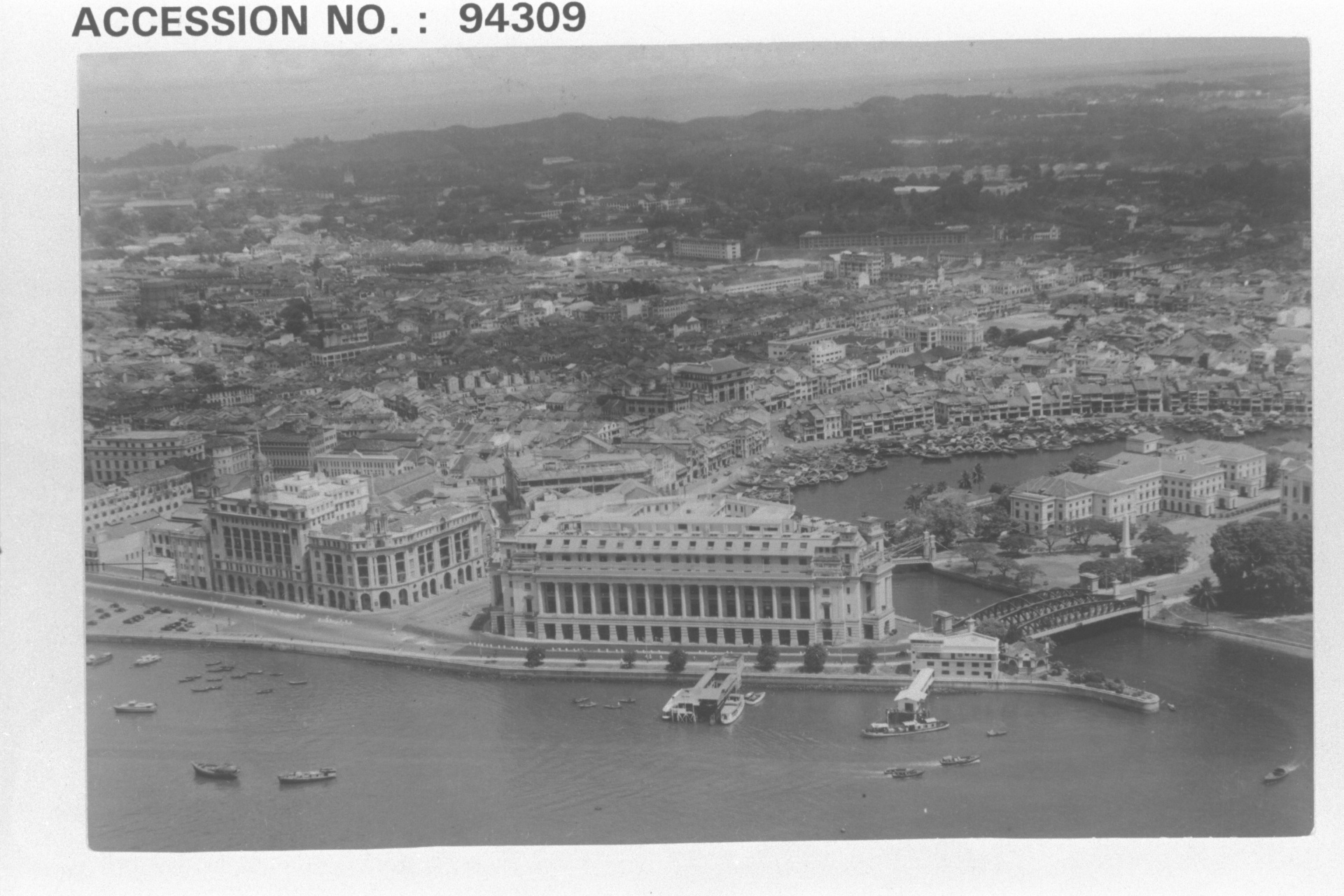

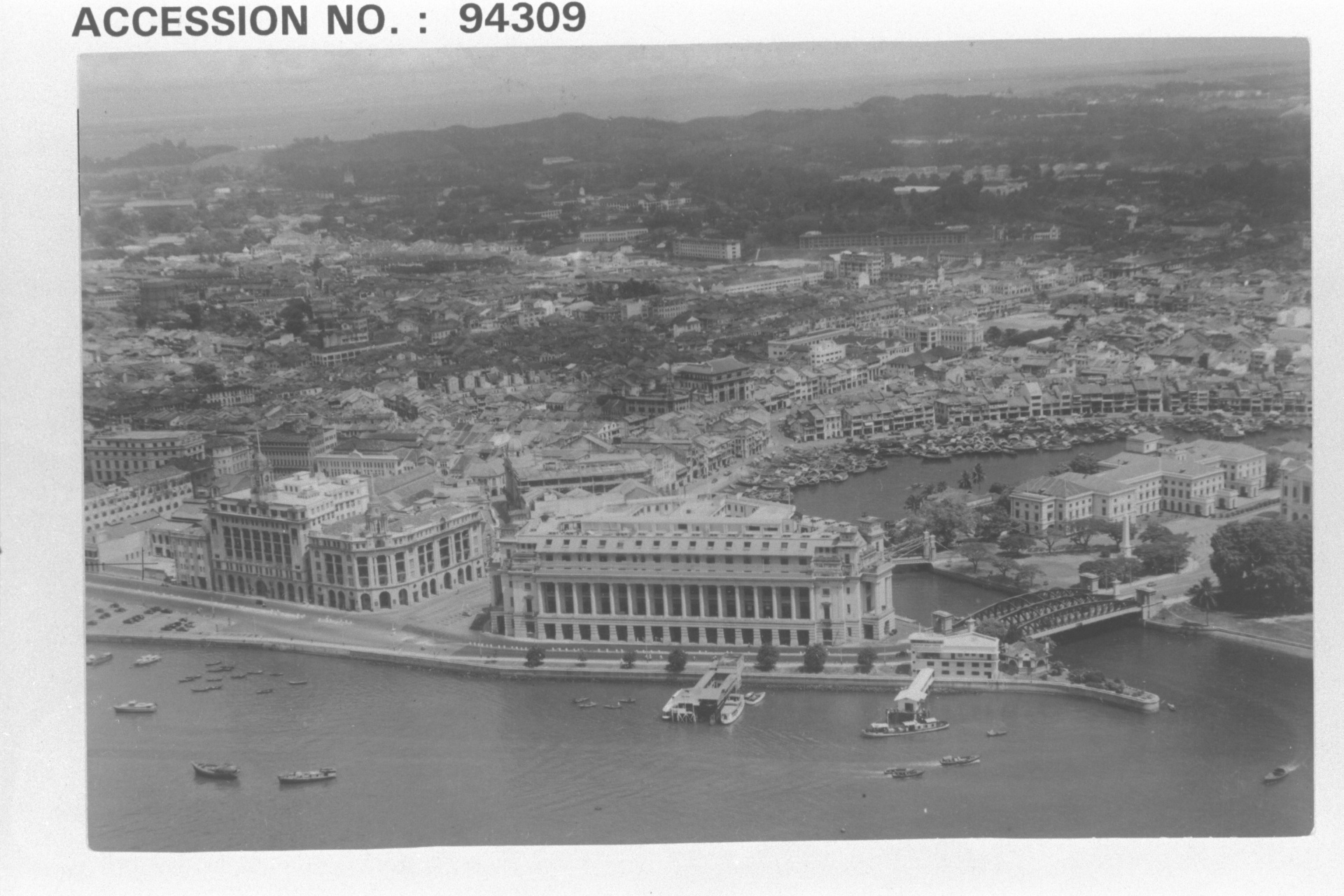

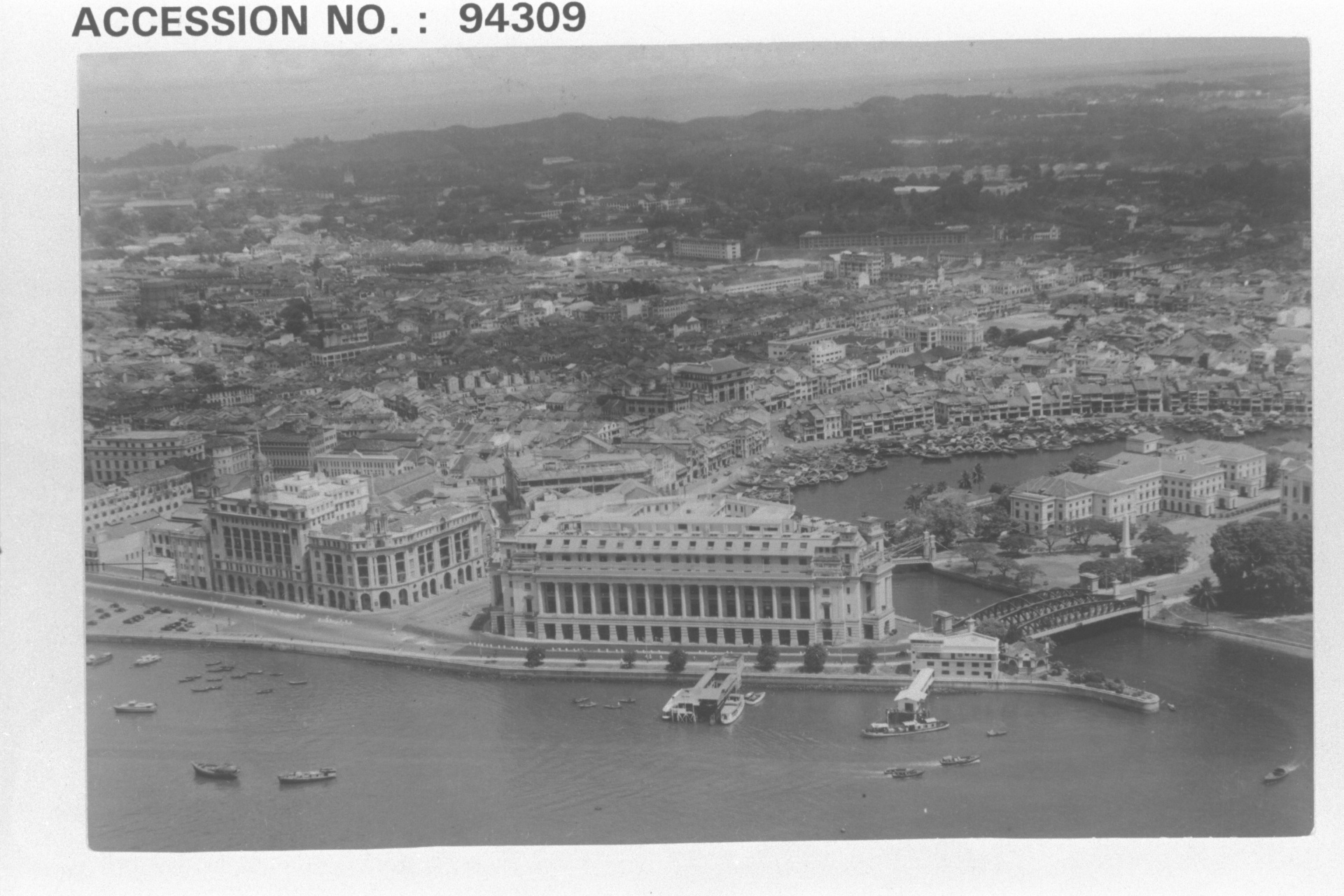

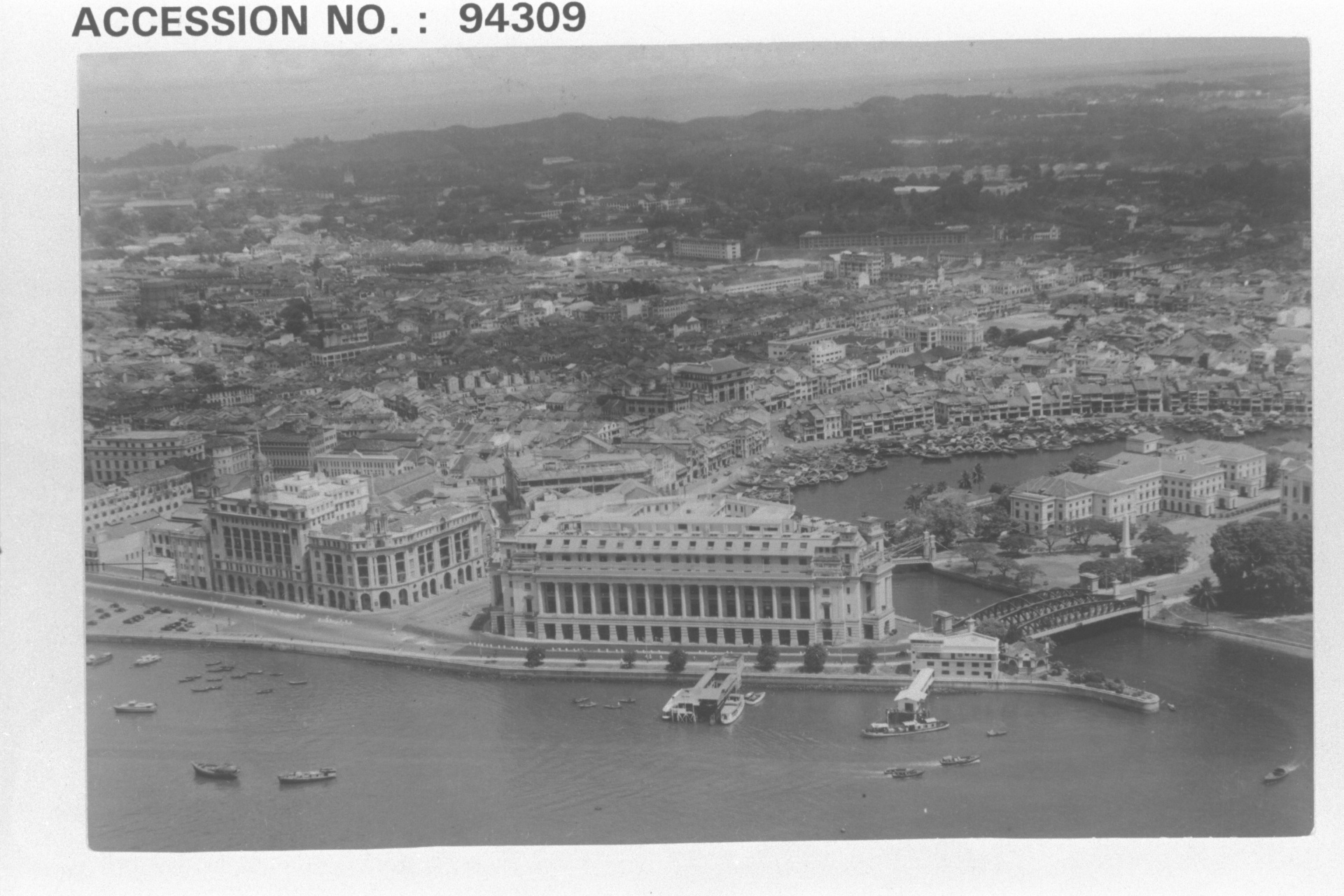

Aerial view of the Singapore river & the waterfront, 1950.

Credit: R Browne Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

January 1946

GENERAL LABOUR UNION’S LARGEST STRIKE

The General Labour Union established by the CPM held its largest strike in January 1946 that lasted for 24 hours and involved 170,000–200,000 workers. The union later re-constituted itself as the Singapore Federation of Trade Unions in August 1946. It gradually came to represent over 56,000 workers through 72 affiliated trade unions by mid-1947. However, while the union seemed independent, it was still subsumed under the CPM’s leadership.

Aerial view of the Singapore river & the waterfront, 1950.

Credit: R Browne Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Credit: R Browne Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

June 1948

STATE OF EMERGENCY DECLARED

In early 1948, a decision taken by the Conference of World Federation of the New Democratic Youth Leagues in Calcutta to resort to armed struggles influenced the Singapore Federation of Trade Unions to organise several pan-Malayan strikes. In one incident, three British planters in Perak were killed.

In response, a State of Emergency was declared by the government in June 1948, resulting in both the CPM and the union being outlawed. The Emergency Regulations were also designed to freeze the funds of the union. Shortly after, officials of the Singapore Federation of Trade Unions went into hiding along with the union’s account books, documents, and funds.

The Emergency Regulations however did not outlaw legitimate trade union activities. Instead, they intensified rivalry among emerging trade unions.

July 1948

FORMATION OF EMPLOYERS’ TRADE UNION

Over 20 employers in Singapore formed the Federation of Industrialists and Traders, a trade union of employers, to protect their collective interests against growing anti-colonial sentiments.

Aerial view of the Singapore river & the waterfront, 1950.

Credit: R Browne Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

1946-1949

RESURFACING OF UNION LINKED TO COMMUNIST PARTY OF MALAYA

After the war, the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) resumed its anti-colonial agenda and activities. Blurring the lines between championing workers’ rights and anti-colonial sentiments, the CPM established a General Labour Union in Singapore and promoted it vigorously. This struck a chord with many Chinese-speaking industrial workers who saw the union as a solution to their poor working conditions.

Aerial view of the Singapore river & the waterfront, 1950.

Credit: R Browne Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

January 1946

GENERAL LABOUR UNION’S LARGEST STRIKE

The General Labour Union established by the CPM held its largest strike in January 1946 that lasted for 24 hours and involved 170,000–200,000 workers. The union later re-constituted itself as the Singapore Federation of Trade Unions in August 1946. It gradually came to represent over 56,000 workers through 72 affiliated trade unions by mid-1947. However, while the union seemed independent, it was still subsumed under the CPM’s leadership.

Aerial view of the Singapore river & the waterfront, 1950.

Credit: R Browne Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Credit: R Browne Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

June 1948

STATE OF EMERGENCY DECLARED

In early 1948, a decision taken by the Conference of World Federation of the New Democratic Youth Leagues in Calcutta to resort to armed struggles influenced the Singapore Federation of Trade Unions to organise several pan-Malayan strikes. In one incident, three British planters in Perak were killed.

In response, a State of Emergency was declared by the government in June 1948, resulting in both the CPM and the union being outlawed. The Emergency Regulations were also designed to freeze the funds of the union. Shortly after, officials of the Singapore Federation of Trade Unions went into hiding along with the union’s account books, documents, and funds.

The Emergency Regulations however did not outlaw legitimate trade union activities. Instead, they intensified rivalry among emerging trade unions.

July 1948

FORMATION OF EMPLOYERS’ TRADE UNION

Over 20 employers in Singapore formed the Federation of Industrialists and Traders, a trade union of employers, to protect their collective interests against growing anti-colonial sentiments.

Aerial view of the Singapore river & the waterfront, 1950.

Credit: R Browne Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

1951

These developments helped to pave the way for the formation of the Singapore Trades Union Congress (STUC) in 1951 under the leadership of Lim Yew Hock, and the STUC subsequently became an affiliate of the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions.

As much as the STUC sought to be more inclusive in representing workers, its composition remained largely English-speaking. In its first annual congress in September 1951, fewer than 30 unions joined, and many of the larger industrial unions did not.

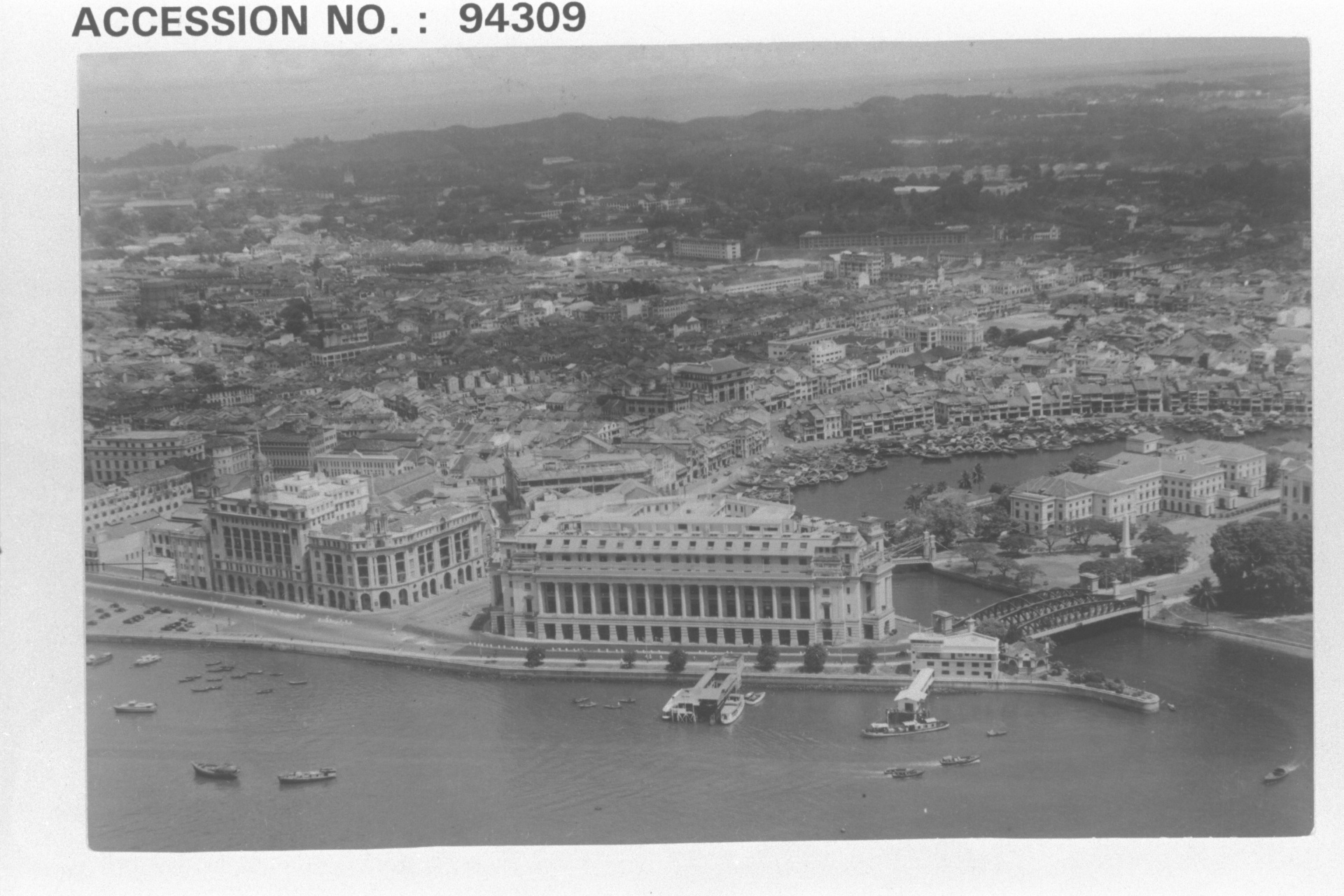

Registration of workers at the Labour Department, 1950.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

1953

In contrast, the employers’ union – the Federation of Industrialists and Traders – was growing. While its name was changed to the Singapore Employers Federation in 1953, its core members were primarily British multinational companies seeking to protect their commercial interests against local trade unions by coordinating wage levels, stabilising labour markets and preventing divide-and-rule tactics by unions.

“Let Singapore City Flourish” sign across St. Andrew’s Road presented by Ho Ho Biscuit Factory Limited, 1951.

Credit: Wong Kwan Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

During this period, employers and unions were not in consultation with each other over labour issues such as wages, working conditions and contracts. Furthermore, many Chinese-educated workers who belonged to the private sector and had formerly joined the CPM-linked Singapore Federation of Trade Unions were not represented by the English-speaking STUC.

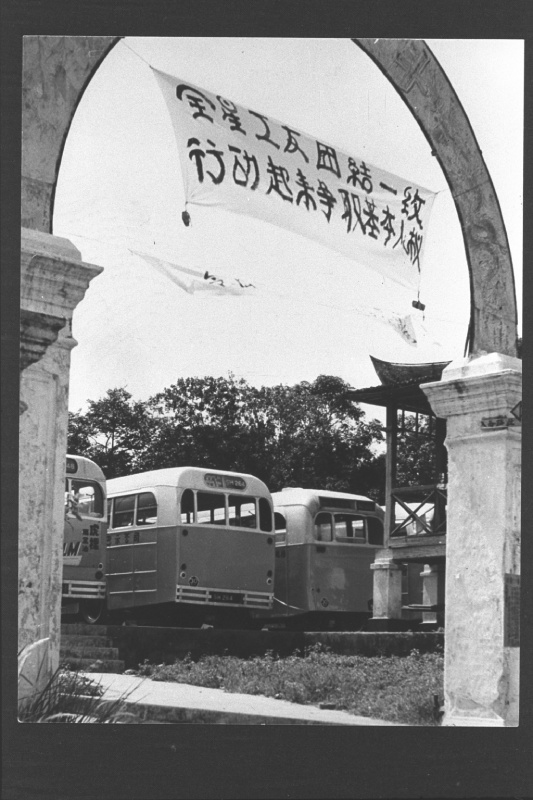

Regardless, the government promoted the growth and development of trade unions by relaxing restrictions on their activities. This in turn encouraged the formal registration of trade unions that sought to represent Chinese-educated industrial workers. The Singapore Factory and Shop Workers’ Union (SFSWU) and Singapore Bus Workers’ Union (SBWU) were two prominent unions that were formed during this time.

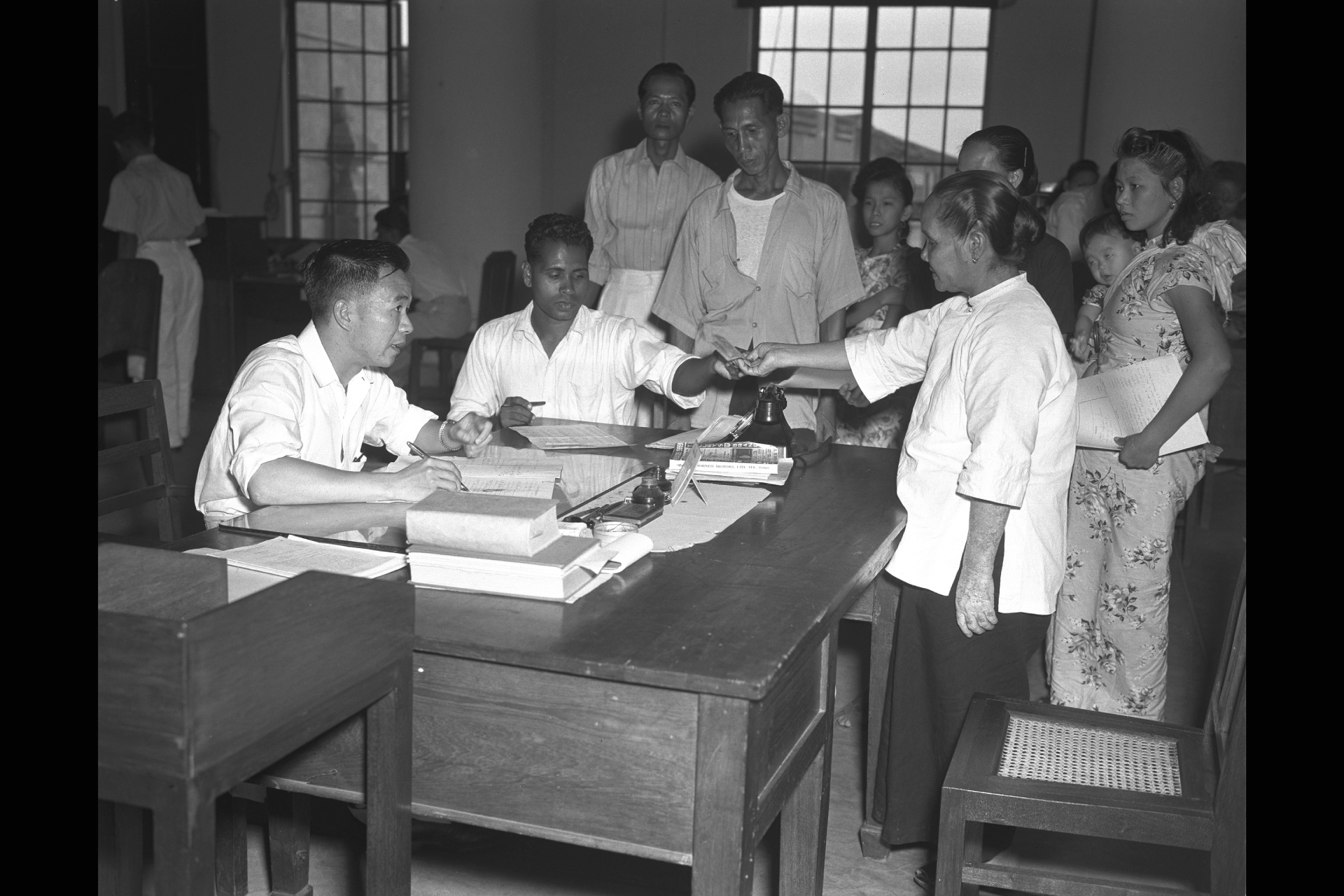

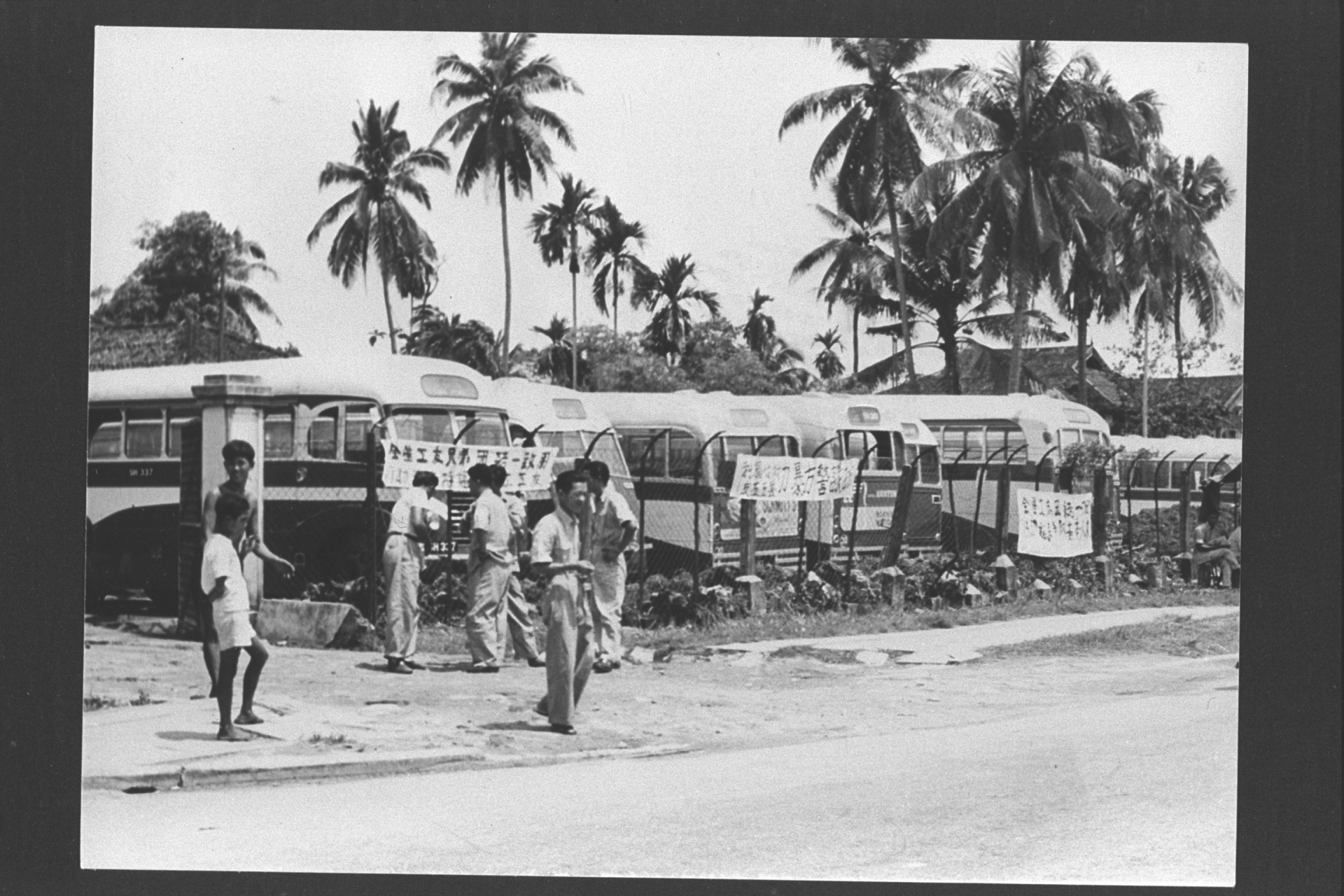

Banners in Chinese at entrance calling workers to cooperate with each other, 1955.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Age of Industrial Action

As the trade union landscape became increasingly divided, so did Singapore’s political landscape. Several political parties began to prepare for Singapore’s partial self-governance as proposed by the British Commission. Many of these parties represented an anti-colonial stance and pushed for an independent Singapore. They also depended on trade unions as their main electoral support.

Banners in Chinese outside gate calling workers to support each other, 1955.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Workers operating the machines inside a factory, 1954.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

The Singapore Labour Party and Singapore Socialist Party aligned with unions of the STUC. On the other hand, the People’s Action Party (PAP), which was inaugurated in November 1954, aligned with unions that belonged to the Chinese-speaking faction, including the SFSWU, SBWU and, by extension, the Singapore Chinese Middle School Student Union.

These unions had grown rapidly. For instance, starting with only 200 workers, the SFSWU expanded to over 30,000 members within ten months.

1955

Buses parked next to gates with banners in Chinese calling on workers to band together, 1955.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Following a watershed election for the Legislative Assembly in 1955 which saw the Labour Front form the government, many Chinese-speaking trade unions began taking a militant stance as they believed the new government had colonial leanings and had modelled their goals on those of the British Labour Party. While these trade unions were initially meant to be championing labour rights, they took on more political fervour in the name of resisting colonialism. Fighting against employers became synonymous with fighting the colonial government.

The relationship between the Chinese-speaking community and the British administration became increasingly strained. From April to September 1955, more than 270 strikes took place, compared to only 13 strikes in the previous two years combined. These strikes involved more than 50,000 workers and a record loss of 946,000 man-days.

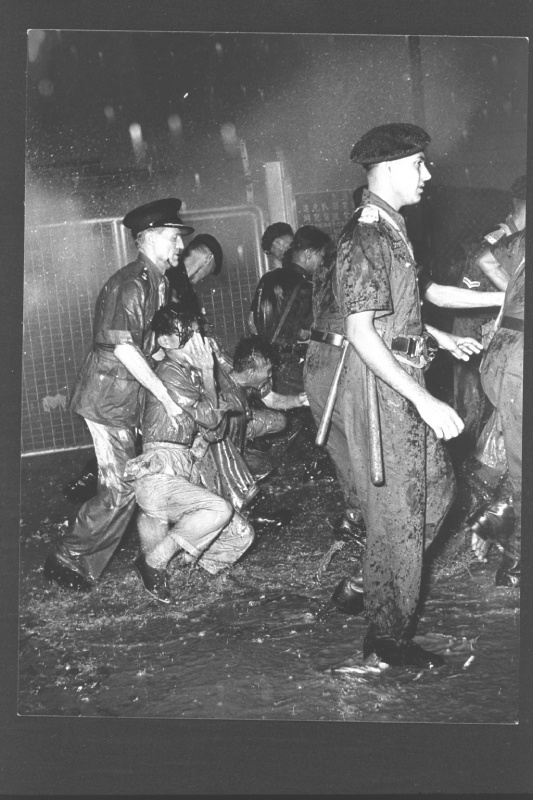

Police erect barricades in Chinatown during the Hock Lee bus riots, 1955.

Credit: Francis Lee Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

The worst of these strikes was the Hock Lee Bus Company riot in May 1955, resulting in 31 injuries and 4 deaths. While Chief Minister David Marshall intervened to plead with the bus company’s management not to fire workers who had joined the newly formed SBWU, his efforts were futile and only further angered the workers.

Related to this riot was a 142-day strike by bus workers of the Singapore Traction Company, the longest strike in post-war Singapore. The series of bus-related strikes brought all bus services to a halt for about a month that same year.

Riot police attending to injured victims at Hock Lee Bus Riots, 1955.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection,

courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

1956

Things took a turn for the worse when workers from the SFSWU joined a planned one-day strike in September 1956 to support students protesting the closure of the Singapore Chinese Middle School Student Union.

The tipping point was in October 1956, when the government of Lim Yew Hock, who replaced David Marshall as Chief Minister of Singapore, approved a Special Branch Security Operation and arrested more than 250 unionists, including PAP’s co-founders Lim Chin Siong and Fong Swee Suan. The Registrar of Society also dissolved the SFSWU on the basis that it was used for purposes inconsistent with its objectives and rules.

While the number of small unions continued to rise, the number of strikes and man-days lost declined following the arrests.

Transitioning Towards

Industrial Peace

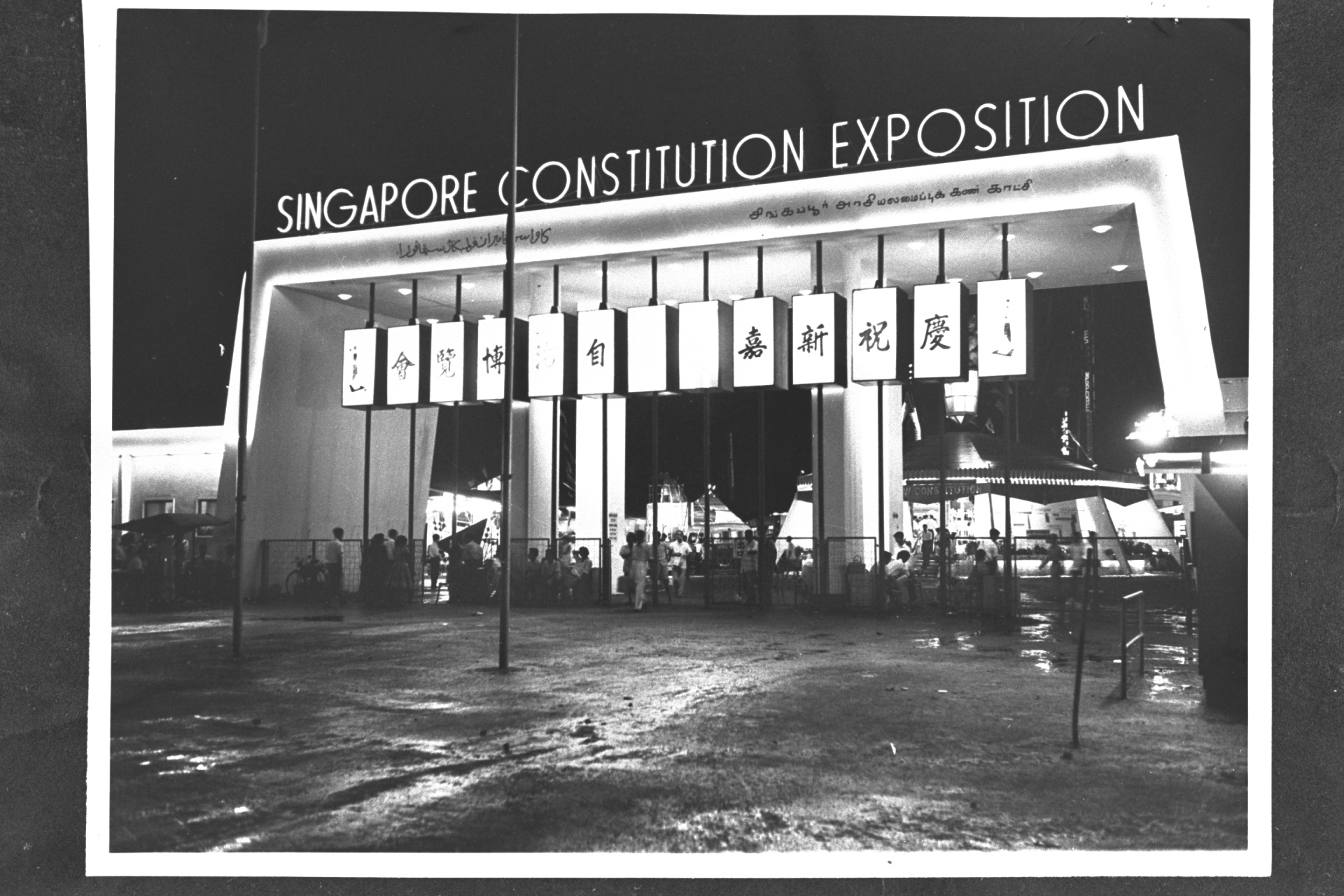

1958

Between 1956 and 1958, talks between the British Colonial Office and several members from the Singapore Legislative Assembly culminated in self-government in Singapore, through the adoption of the 1958 State of Singapore Constitution. The Singapore government was given full internal governing powers, except for internal security and defence matters.

Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce organises “Singapore Constitution Exposition” at Old Kallang Airport to celebrate self-government, 1959.

Credit: Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

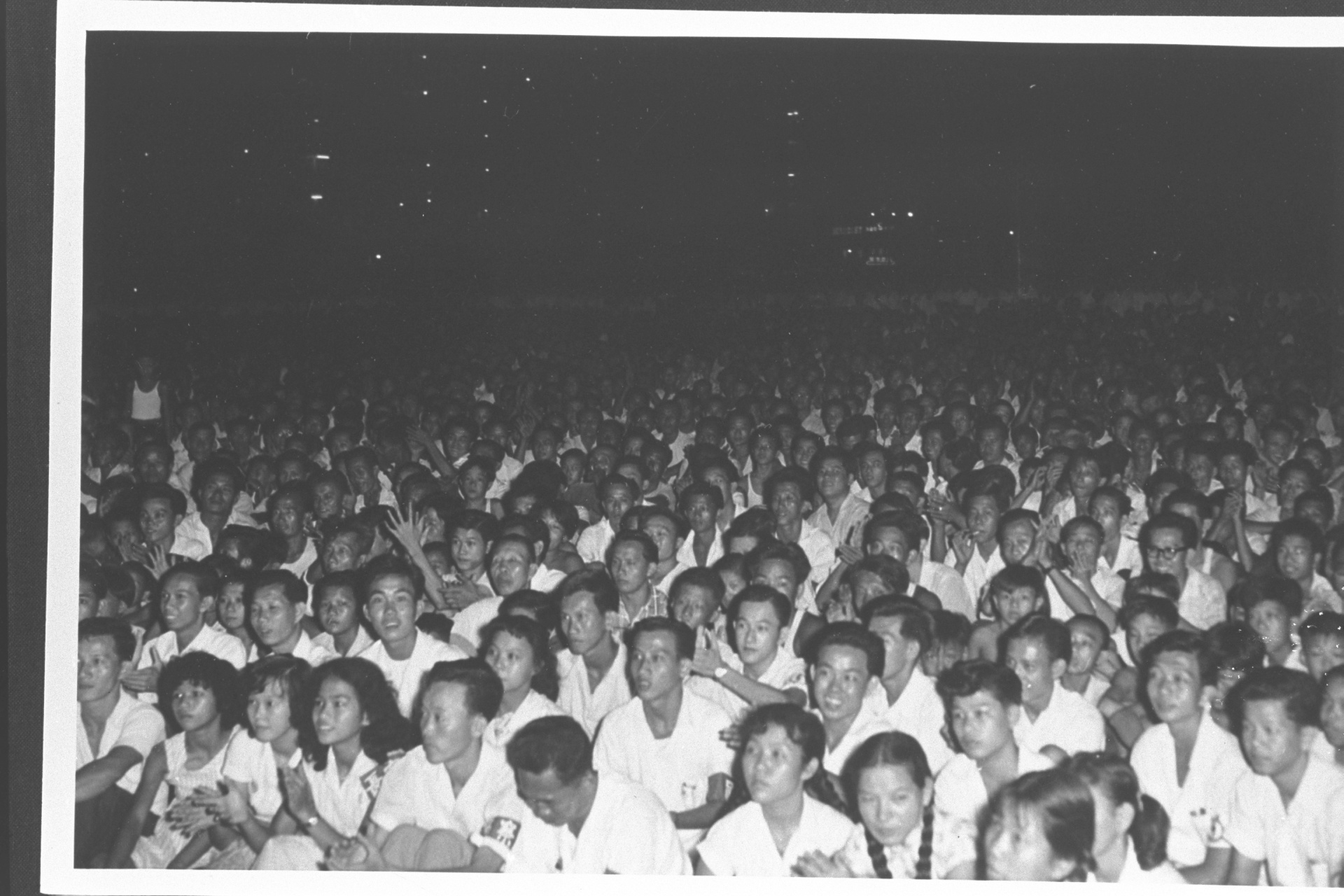

General election campaign by political parties, 1959.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

1959

With the new constitution, an election for 51 seats in the Legislative Assembly was held in May 1959. The PAP won the election with the large support base it had accumulated by supporting several unions. The new PAP government, led by Lee Kuan Yew who became Singapore’s first prime minister, aimed to achieve “industrial peace with justice”. The government made it a top priority to unify and strengthen the trade union movement, while minimising disruptions to Singapore’s society and economy.

The government knew that it had to play the role of arbitrator between the trade unions and employers. It introduced the Trade Unions (Amendment) Bill which gave the Registrar of Trade Unions powers to reject or deregister trade unions, purportedly to ensure effective representation of workers and prevent jurisdictional disputes between trade unions. Meanwhile, the government strongly encouraged aligned and allied trade unions to amalgamate. For instance, a Federation of Land Transport Workers was subsequently formed by the SBWU, the Singapore Traction Company Employees Union and the Singapore Taxi Drivers Union.

More importantly, the government passed the Industrial Relations Ordinance that established an Industrial Arbitration Court (IAC) in 1960.

PAP election rally in Chinatown, 1959.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

1961

The Industrial Arbitration Court

Industrial Arbitration Court – case being heard in the court, 1962.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Under the Industrial Relations Ordinance (1960) which established the IAC in 1960, the IAC could make contract rules, including on wage matters, on behalf of the relevant parties when they could not reach a consensus. The IAC could also interpret and apply contract rules as well as implement a general system of collective bargaining.

However, both workers and employers had to be willing to partake in its proceedings. Under the Industrial Relations Ordinance, in order to refer disputes to the IAC, the workers and the employers had to jointly agree to enter arbitration.

In the IAC, the parties in dispute could only speak through representatives, such as industrial relations officers appointed by them. Both parties also had to accept that industrial action would not be permitted once the IAC has taken up the dispute.

If neither of the parties agreed to take the dispute to arbitration, the Minister of Labour or the Yang di-Pertuan Negara (Head of State) could refer the dispute to the IAC.

The IAC process thus helped to set the stage for all parties – government, employers and employees – to participate in dispute resolution, providing a precedent for a tripartite approach to industrial relations in Singapore. The IAC also contributed to the reshaping of attitudes towards industrial relations among tripartite partners through the institutionalisation of collective bargaining.

Industrial Arbitration Court – case being heard in the court, 1962.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Former IAC President Tan Boon Chiang, recounted how the IAC worked with the trade unions:

“At the beginning, it was difficult. But later on, they became more flexible and were able to concede to one another. You give me point A and I concede point B to you. So that sometimes, after two or three days of hearing they can settle [the dispute amicably]. It is very easy that way. So, when the problems are resolved, I would direct them back to the registrar, they produced a written award and I approved the written awards. And of course, by that time, [the IAC] had set some patterns… so many previous collective agreements agreed upon and approved… and they become the precedents for your next negotiation. So that brought about industrial peace… So in that sense, the IAC was a kind of pioneer at that time on how we can make tripartism succeed… The maturing process is slow. You cannot pinpoint a particular period of time when suddenly they became friendly.”

Some compromises also had to be made by employers. For instance, in its 1960/61 annual report, the Singapore Employers Federation “did not consider that a system of compulsory arbitration such as was proposed was the best method of bringing about real and lasting industrial peace in Singapore.” A few years later however, it acknowledged in its 1966/67 report that in most cases, the IAC had upheld employers’ right to retrench workers.

Rise of National Trades Union Congress (NTUC)

Following the passing of the Industrial Relations Ordinance, the government published a strategy paper titled “The Labour Movement and Industrial Expansion”. The paper sought to define the role of organised labour and called for industrial peace amid Singapore’s competition for investors against Hong Kong. The STUC secretariat also supported this strategy. However, it was to be only a temporary consensus between the government and the STUC.

Disagreements arose over Singapore’s inclusion within the larger Federation of Malaya, which manifested during the 1961 by-election in Anson and later led to a split within the PAP.

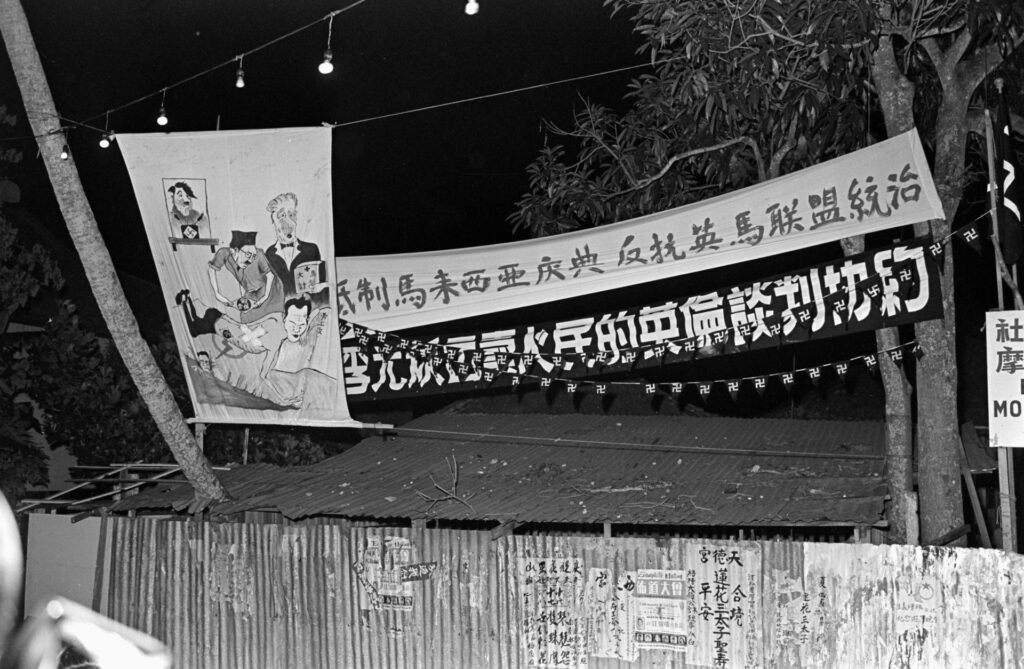

Barisan Sosialis protest banners and posters on merger during Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s walkabout in Joo Chiat Constituency, 1963.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Prior to the election, six PAP leaders who were also STUC secretaries issued a statement that the merger with Malaya was not urgent.

This contributed to the defeat of the STUC President who was standing as a PAP candidate in the by-election.

The differing priorities led to the expulsion of 13 PAP assemblymen who later formed the Barisan Sosialis (Socialist Front), and the dissolution of the STUC. To fill the void left by the STUC, a Singapore Association of Trade Unions (SATU) was formed by the Barisan Sosialis faction, and a National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) was established by the remaining supporters of the PAP. In terms of size, SATU had a larger representation – commanding most of the existing trade unions – while only 12 of 95 unions allowed the NTUC to represent them. SATU continued to stage strikes – more than 70 strikes involving almost 40,000 workers – to oppose Singapore’s merger with Malaya.

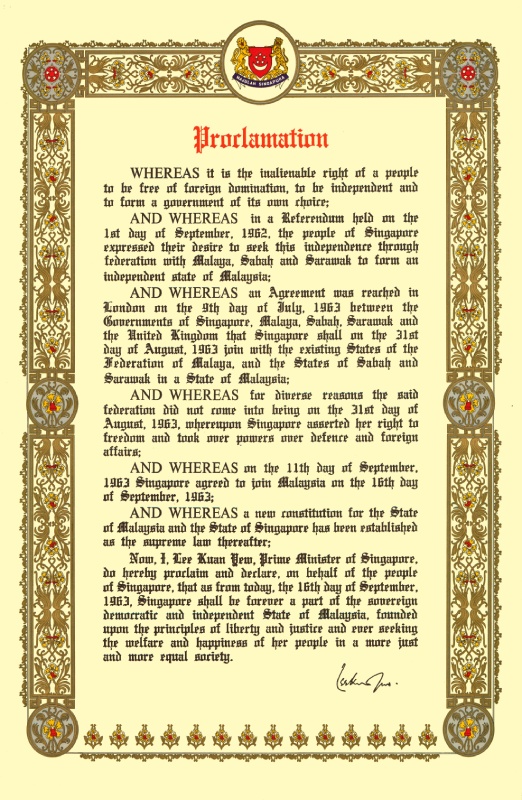

The Proclamation of Singapore’s merger with Malaysia on 16 September 1963, signed by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, 1963.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

However, SATU’s prominence was short-lived. An inquiry by the Registrar of Trade Unions into the affairs of the Singapore Harbour Board Staff Association (which was under SATU) was followed by the Registrar’s cancellation of seven unions’ certificates. These actions were taken on the grounds that they had participated in communist activities which threatened state security.

More than 100 pro-communist and anti-Malaysia leaders were arrested, many of whom were SATU’s leading figures. After SATU called unsuccessfully for a two-day island-wide strike to protest the Registrar’s actions against various SATU-led unions, several unions began to leave the umbrella of SATU. At least five SATU-led unions joined the Singapore Manual and Mercantile Workers Union, which was an affiliate of the NTUC. In October 1963, the Registrar refused the registration of SATU as a federation of unions on the basis that the organisation was veering towards unlawful purposes.

Meanwhile, the merger with Malaya proceeded. On 16 September 1963, Singapore became part of the Federation of Malaysia, together with Malaya, Sarawak and North Borneo (now Sabah). This lasted until 9 August 1965 when Singapore separated from Malaysia and became an independent nation.

1964

The NTUC was formally registered in 1964 and began to strengthen its relations with the PAP government. The senior leadership of the NTUC called upon the PAP government to be more involved in the congress’s mission. The Secretary General of the NTUC at the time, Devan Nair, requested then Acting Minister for Labour, Ong Pang Boon, to establish a centralised labour research unit to increase the union’s in-house expertise on labour-employer matters. The government accepted the NTUC’s proposal and seconded several public servants to the unit.

Devan Nair at the first NTUC annual delegates conference, 1962.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

1965

By October 1965, the research unit became incorporated into the NTUC. Equipped with technical knowledge and expertise in negotiating union cases with employers, the NTUC also presented union cases before the IAC.

The NTUC began to work closely with employers to maintain industrial peace with the view of expanding the Singapore economy through faster industrial growth.

For instance, the NTUC declared a joint Charter for Industrial Progress in January 1965 with the Singapore Manufacturers’ Association and the Singapore Employers Federation. The Charter established the parties’ commitment to work as partners in the industrialisation agenda, while supporting the formation of a State Economic Consultative Council for developing and implementing socio-economic policies.

The NTUC established a Productivity Code of Practice which called for parties to jointly refer to arbitration any dispute which could not be resolved through direct negotiations, rather than taking industrial action. Furthermore, the Code of Practice called for long-term collective agreements of up to three years to be concluded based on fairness and justice.

May Day rally organised by NTUC at National Theatre, 1965.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

(Front row, from left) Minister for Law and National Development E. W. Barker, Secretary-General of NTUC C. V. Devan Nair, and NTUC Chairman Ho See Beng at the closing ceremony of NTUC Convention held at Trade Union House in Shenton Way, 1965.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Afro-Asian trade unionists attending the Second Convention of NTUC, meet reporters, 1965.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Over time, the NTUC grew its international presence; from organising a week-long “International Labour Seminar on the Problems of Workers in Developing Countries” in October 1965 involving trade unionists from 34 countries, to visiting African countries as a member of the Malaysian Goodwill Mission to Africa.

In 1965, Singapore became a full member of the International Labour Organization and was elected a member of the Asian Advisory Committee at its International Labour Conference. During 1968-69, Singapore was also chosen as the venue for several international trade union meetings.

Reformulating union regulations and employment conditions

As Singapore gained independence from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, the PAP government instituted reforms to reduce industrial action and increase arbitration as a mode of resolution.

The Trade Unions (Amendment) Act was passed in August 1966, disqualifying non-Singapore citizens and persons with criminal records from holding office in or being employed by trade unions. The Act also restricted statutory board employees to joining the unions representing their respective statutory boards, in order to limit the influence of larger public sector unions.

1967

A Criminal Law (Temporary Provisions) Act was amended in 1967, making it unlawful for workers to go on strike, and for employers to lock workers out, in essential services such as water, gas and electricity. Additionally, for those working in essential services, strikes or lockouts required at least 14 days’ notice.

1968

The Government then amended the Industrial Relations Act in 1968 to redefine the scope of collective bargaining between management and trade unions. Specifically, the Act gave management full discretionary powers over matters relating to recruitment, proposal, dismissal, retrenchment and transfer of workers, thereby making these matters non-negotiable for workers. The IAC would not, in most cases, hear disputes concerning the dismissal or reinstatement of an employee. Instead, the Minister for Labour would review such cases and, where appropriate, order an employer to reinstate or compensate the affected employee. The Act also extended the duration of collective bargaining agreements from the previous range of 1.5–3 years to a minimum of three years and up to five years.

An Employment Act was also introduced in 1968 to link wages to efficiency and productivity. A ceiling was introduced to the number of annual and sick leave days that could be taken while standardising the working week to 44 hours.

In his 1979 May Day Message, Singapore’s founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew said:

“The close co-operation between the political and the union leadership made modern Singapore. It is both history and today’s reality. We have advanced because the government and the unions moved in tandem. Promising unionists were fielded by PAP to be Members of Parliament. And PAP Members of Parliament with no union experience have been inducted into union activities. The future of Singapore depends on our strengthening this symbiosis between government and unions. We must strengthen these relationships to make our future secure.”

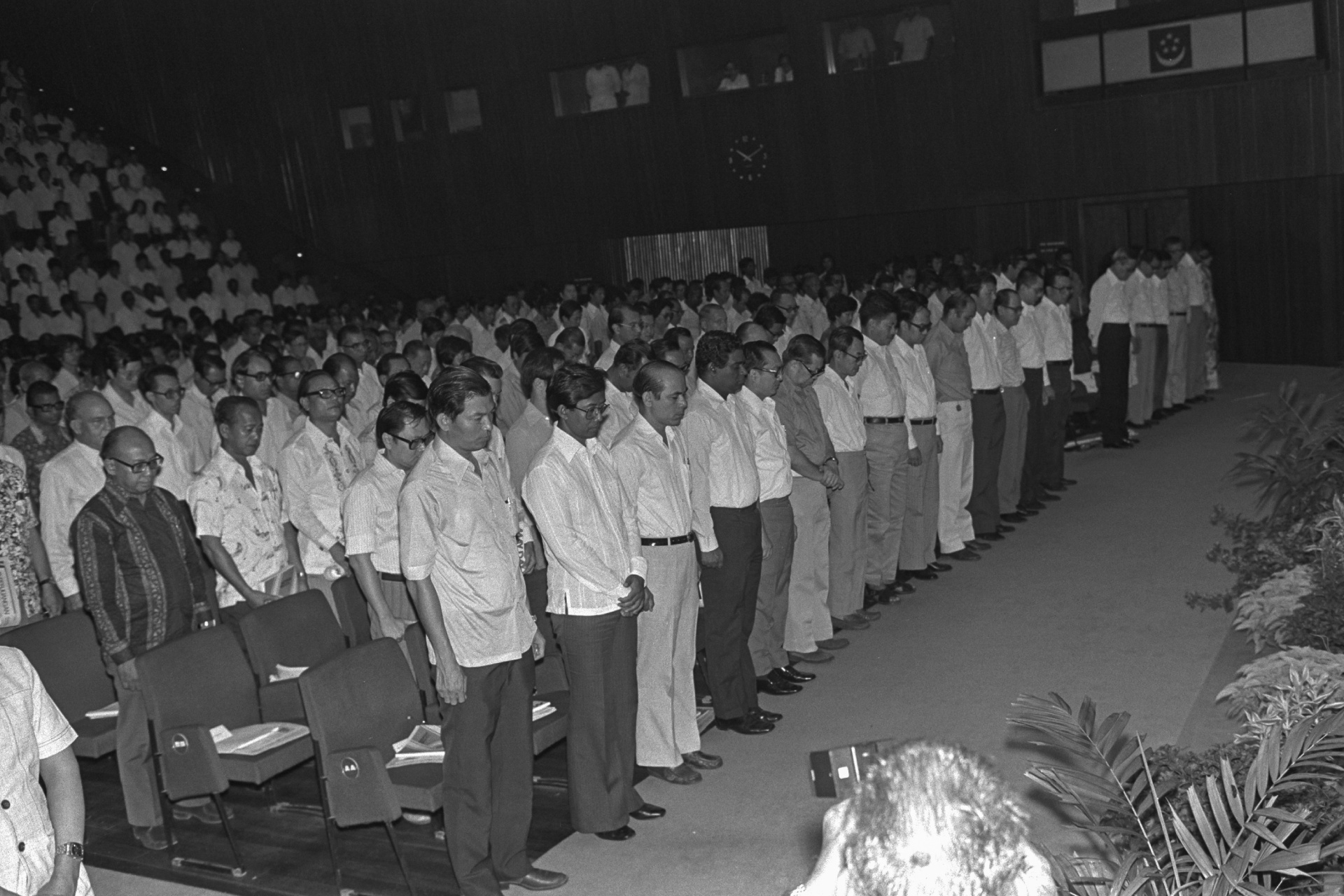

Guests and union members at the NTUC’s 1979 May Day Rally at Singapore Conference Hall, Shenton Way, 1979.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

As industrial actions slowed over time, union membership fell. Between 1964 and 1968, labour union membership fell by 20%. The PAP government took this opportunity to strengthen its relationship with the union movement.

First, it co-opted several central committee members of the NTUC to stand as parliamentary candidates in the 1968 general elections. Then, in a bid to revive participation in the labour movement, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew gave the opening address at an NTUC seminar on “Modernisation of the Labour Movement” in November 1969, calling for the union movement to shed its role as “a combat organization… for class war”. Other PAP leaders, including S. Rajaratnam and Goh Keng Swee, also delivered keynote speeches persuading unionists to look after the interests of workers while identifying the unions’ interests with those of the nation. In the same vein, then secretary-general of the NTUC, Devan Nair, expounded on the need for tripartism, calling on trade unions to shoulder the responsibility for workers’ performance as part of their industrial relations.

A tripartite body was proposed by the NTUC that would consist of representatives from the government, management and organised labour. It would be responsible for formulating and implementing industry-specific wage guidelines whilst considering the economic performance of the country.

1970

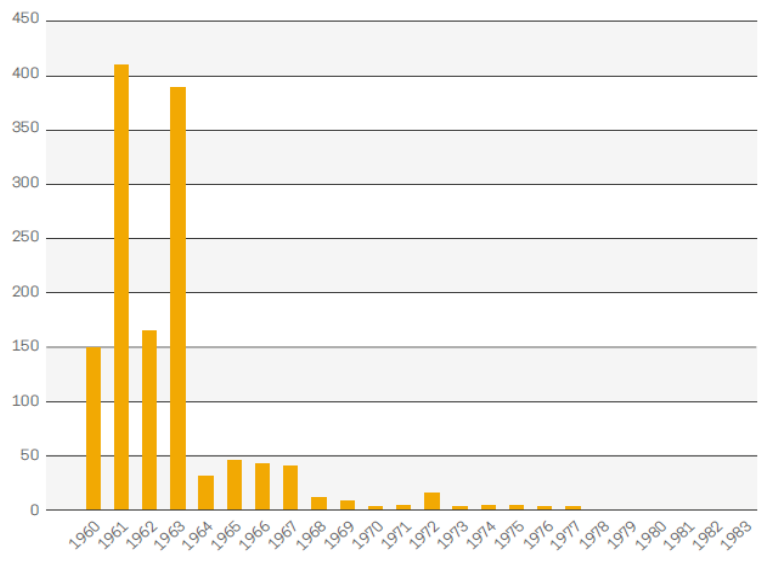

Following the establishment of the IAC and the introduction of various labour-related policies and legislation in the 1960s, the number of strikes dipped from nearly 200 in 1963 to fewer than 50 per year from 1964 onwards. The number of man-days lost to industrial action declined in parallel.

Conversely, the number of awards delivered by the IAC relating to industrial disputes increased ten-fold by 1963, as compared to that in its first 15 months of operation. As a result of the surge in industrial dispute cases, a second Court was constituted in 1962. This Court ceased functioning in 1970 as dispute cases gradually fell.

Man-days lost to industrial action (‘000), 1960-1983

Source: Albert Winsemius, The Dynamics of a Developing Nation–Singapore, 1984.

The concept of a wages council was floated by Finance Minister Hon Sui Sen during a Singapore Manufacturers Association dinner in June 1971:

“… wages and benefits will have a tendency to rise. It will be necessary to devise bonus and incentive schemes or establish wages councils wherein increases in wage costs on an industry basis can be coolly considering in the interest of both employers and workers, and of the public represented by the government.”