TRIPARTISM

Tripartism in Wage Negotiation

scroll to explore

While stronger bonds had been forged between the government and unions in the early years of independence, against a backdrop of growing prosperity, there was a fear that unchecked collective bargaining would cause wage growth to become unsustainable and hamper economic development. Something had to be done.

Establishing the

National Wages Council (NWC)

1972

In 1972, the government established the National Wages Council (NWC), following a suggestion from Albert Winsemius, an economic adviser to the Singapore government. The NWC would serve as a tripartite platform to facilitate social dialogue between the government, labour unions and employer associations on wage-related issues.

Since its establishment, the main objective of the NWC has been to facilitate orderly wage adjustments at the national level by issuing annual wage adjustment guidelines. The NWC strives to avoid strikes, lockouts or protracted wage negotiations that would be detrimental to businesses. In more recent years, the NWC wage guidelines has also advocated for the adoption of specific wage policies to improve Singapore’s economic competitiveness.

Economics Professor Lim Chong Yah, who served as the NWC’s first chairman (1972 to 2001), elaborates on why the NWC was established:

The Role of the NWC

One of the NWC’s core functions is to issue annual wage guidelines at the national level with the stated goal of sustainable improvements in real wages. Every year, NWC members meet for discussions that culminate in wage guidelines that are then submitted to the Cabinet. Once endorsed, these guidelines are publicly gazetted by the Ministry of Manpower (MOM).

To arrive at these wage guidelines, NWC members weigh various factors, adopting the lenses of both employers and workers. Achieving its main objective of economic growth alongside equity requires the NWC to balance real wage increases against other concerns such as the ability of employers to afford such increases, the cost of living, and economic sentiment. Data commonly discussed at the NWC include the rate of inflation, economic growth, labour productivity, unemployment rate and other national econometric data. Members are also allowed to submit position papers for consideration and debate.

Within the NWC, the three major partners are all represented – government, employers and employees. Employee representatives come from the senior ranks of the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) and major unions. Employers are represented by the leaders of various business associations including the Singapore National Employers Federation (SNEF), Singapore Business Federation (SBF), trade associations and chambers of commerce. Government representatives usually hail from various departments across economic and social ministries and statutory boards. By design, the three partners nominate equal numbers of representatives to the NWC for parity in representation.

At the NWC level, discussions are moderated by a neutral chairperson. The chairperson guides discussions and ensures that the various tripartite partners have space to share their opinions and concerns. Discussants are encouraged to arrive at an agreement without being forced into one by a majority or the chairperson.

Peter Seah, Chairman of the NWC (2015 to present), explains how the role of the chairperson as a neutral arbiter helps the different partners come to consensus at their own pace rather than forcing consensus upon them:

As for the unions’ role in ensuring a fair share for workers, Cham Hui Fong, Deputy Secretary General of the NTUC (2020 to present), reveals how a strong relationship between unions and employers benefits both sides:

Koh Juan Kiat, former Executive Director of SNEF (1995 to 2020), discusses how gathering feedback from constituents is a crucial step towards securing consensus among tripartite partners:

Ong Yen Her, former Divisional Director for Labour Relations and Workplaces at the Ministry of Manpower (1985-2012), describes how the government plays a facilitating role in negotiations:

Negotiation principles and

implementation of wage guidelines

Since its creation, deliberations at the NWC have been governed by a few core principles – the unanimity principle, the Chatham House principle and the finality principle.

First, under the unanimity principle, wage guidelines must be supported by all parties. While this means that lengthy negotiations may be required to achieve consensus, it also ensures that the final set of wage guidelines has the broadest possible level of support and the highest likelihood of adoption. Unanimity (rather than majority rule) also means that no two parties can collude against the third.

Second, the Chatham House principle facilitates frank discussion within the NWC, since controversial or unpopular views cannot be publicly shared.

The finality principle means that all parties must consult their respective constituents beforehand to understand their demands, so that the representatives are empowered to negotiate on constituents’ behalf and decisions taken at the Council are final. No other formal rules govern discussions at the NWC.

Professor Lim Chong Yah, the founding Chairman of the NWC, discusses the fundamental principles that govern the council:

“One is there’s the Chatham House Rule. Chatham House Rules means that of non-attribution. That means that whatever we say in the council, we don’t go out to tell the newspapers… [otherwise] there will be open confrontation instead of arguments within the room. There were very often quite serious arguments within the room. But it didn’t create disequilibrium outside the room…

The second principle is not very well-known. It is called the unanimity principle. The unanimity principle is not quite the same as the consensus. Consensus implies the majority can decide and then the rest follow. So, I could not imagine that if the unions and their employers were to decide and the government had to follow… Similarly, government and the employers or the unions can decide and the other third party must follow. I think that would break the [NWC] straightaway, right from the beginning… So, you see all the signatures of the participants [in the NWC guidelines], every year… Then as a chairman, I would try to make sure that all their names are published in the newspapers. That we were unanimous on the subjects we want to do…

The third principle which [is] a little bit unusual for an industrial democracy, that is the finality principle… That is when you have agreed, you have signed the document, that is final… In other words, you don’t go back to your stakeholders, your constituents and get their agreement. But in a normal industrial democracy, that is the practice – you go back to your constituents to get endorsements… I know how this could make it very, very difficult for the NWC to work. When we have agreed, we have signed, that is the finality… you must get authorisation from your organisation first… these principles worked out very well in Singapore.”

Lim Swee Say, Secretary-General of the NTUC (2007 to 2015) and Minister for Manpower (2015 to 2018), explains how regular interactions among tripartite partners help to smoothen the negotiation process at NWC:

“The interesting thing is that after so many years of tripartism, say in the case of NWC, we seldom get into the deadlock situation. We seldom get into a so-called confrontational situation… Because the tripartite partnership in Singapore is not a once-a-year [interaction]… we don’t work separately and wait for the NWC season, and then sit down to talk about what we should do together in setting wage policy. In fact, tripartism happens on a daily basis, on a weekly basis, on a monthly basis throughout the year. So, by the time we come to the table to negotiate wage policies, all of us are on the same wavelength.

So, for example, there will be times where we focus on low-wage workers. But we don’t come to the NWC to talk about low-wage workers. By then, different parties may have different views. But since we’ve been working on the issues on a continuous basis throughout the year, so by the time we come to be NWC, it’s another checkpoint, another milestone… the continuity is already there… I would say that it’s because of this very tight, very close partnership throughout the year. So as a result, I would say we end up having no surprises when we come to the NWC.”

What is less familiar to many is that the NWC Guidelines are not legally binding – this is a deliberate choice, as broad wage guidelines were deemed to be too crude to cover every possible employment situation. Legally binding wage guidelines would also hamper businesses from adjusting wages to their specific operating contexts.

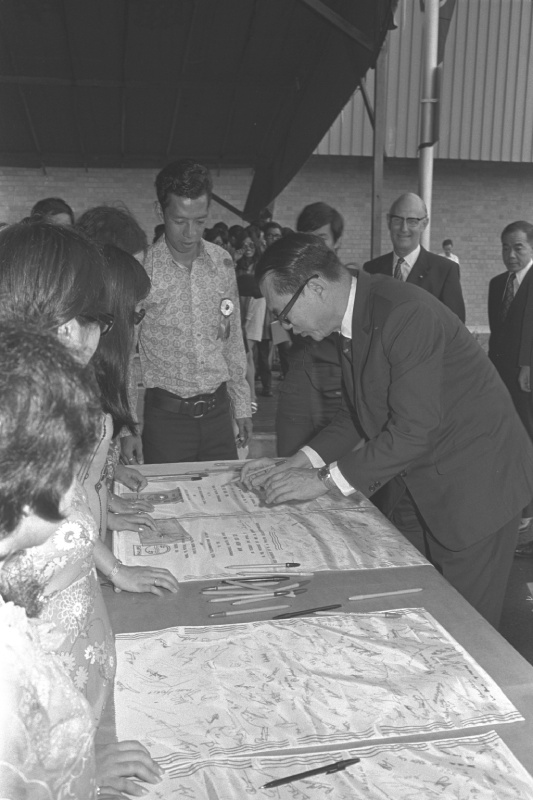

National Wage Council meeting, 1976.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

In practice, many businesses and their employees in Singapore do rely on the NWC wage guidelines at least as a starting point for wage setting and negotiations, modifying the recommended wage adjustments upwards or downwards accordingly. Moreover, the NWC wage guidelines help to level the playing field between companies, reducing the likelihood of salary competition by discouraging excessive wage increases that run ahead of productivity. Most importantly, the unanimity principle behind the wage guidelines means that they are collectively endorsed by the government, labour unions and business associations, which gives them significant social legitimacy.

Stephen Lee, former President of SNEF (1988 to 2014), elaborates on why the NWC’s non-legally binding wage guidelines are still closely adhered to by companies, and describes how SNEF works with its members to resolve implementation issues following the announcement of the NWC wage guidelines:

Cham Hui Fong, current Deputy Secretary-General of the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC), explains the difference in adherence to NWC wage guidelines between unionised and non-unionised companies:

“It’s not a mandatory guideline… [But] there must be a difference between unionised companies and non-unionised companies. In the unionised companies, we must understand NWC is gazetted. If there is a dispute and there are strong grounds to push for certain wage adjustment based on the guidelines, we have every right to refer the case to the ministry, [and] of course to the Industrial Arbitration Court. And the court will arbitrate based on what are the guidelines and based on the reasonableness that both parties have put forth. So, those in the unionised companies will understand that whatever they have gotten is being bargained for… collectively bargained, representing the group of workers and to ensure that it’s win-win for both. So, even though it’s not mandatory, yes, there is a difference because you are in unionised companies.”

Building Trust

The process by which NWC manages the discussions that lead to its annual wage guidelines is designed to be conducive to problem solving and compromise. The NWC members share data and views on the national economic context before decisions are taken. This ensures that decisions are not made in isolation and that the tripartite leadership is in tune with the interests that they represent. Beyond the formal setting of the NWC, the interactions that NWC members have outside formal meetings also help with trust-building and camaraderie. This relationship between the tripartite partners, while not always frictionless, has stood the test of several crises.

To Professor Lim Pin, second chairman of the NWC (2001 to 2015), the tripartite partners’ motivations to find common ground is partly rooted in Singapore’s vulnerabilities as a small country:

Aubeck Kam, Permanent Secretary of Ministry of Manpower (2016 to 2022), recalls how the parties in the NWC often try to seek common ground, and how trust built up from regular collaboration makes it easier to solve more challenging problems in times of crisis:

Lim Boon Heng, Secretary-General of the NTUC (1993 to 2006) and Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office (2001 to 2011), describes how conscious efforts to develop open communication and tripartite representation across public institutions in Singapore over the years strengthens public trust:

For Mary Liew, President of NTUC (2015 to 2023), the process of building trust among the tripartite partners in the past was not without friction, but this trust is especially important during unprecedented times such as the Covid-19 pandemic:

Balancing wage growth with

economic competitiveness

From the NWC’s creation in 1972 to 1996, wages in Singapore increased by an average of 4.9% annually in real terms. Although achieving sustained increases in real wages is an important objective for the NWC, the council is also careful to do so without adversely affecting Singapore’s overall economic competitiveness or business environment.

1985

Minister for Finance Hon Sui Sen opens Philips

Machine Factory and Telecommunications Factory at Jalan Ahmad Ibrahim, 1973.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Relative economic competitiveness is especially important for Singapore as an open economy. Singapore competes internationally for investment capital, and its small domestic market means that almost all of its industrial output is exported. Policymakers are often concerned that increases in relative business costs may affect Singapore’s export competitiveness and attractiveness as an investment destination.

When Singapore experienced a recession in 1985, a loss of cost competitiveness relative to other regional export-oriented economies was identified as one of the contributing factors. In response, the government implemented drastic reductions in wage costs through direct cuts to contributions towards the Central Provident Fund (CPF), Singapore’s defined contribution pension fund.

Till today, the country’s relative economic competitiveness remains a central consideration in policymaking, and the NWC’s recommended wage adjustments have lagged labour productivity growth rates since the late 1980s. This is thought to be the best approach for delivering wage growth without eroding the country’s economic competitiveness.

Minister of State for Education Dr Tay Eng Soon leads team of Vocational and Industrial Training Board officials in visit to Cold Storage Gourmet Foods Factory at 18 Chin Bee Avenue, 1983.

Credit: Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Although Singaporean employees have enjoyed wage improvements over the years, the NWC does not always recommend wage increases in its annual guidelines. The NWC has, on a number of occasions, recommended wage restraint and even wage cuts, on grounds that these will help to preserve jobs. Such guidelines are issued in response to serious economic shocks such as recessions and public health crises. Downward adjustments in real wages or reduced pace of wage increases aim to preserve jobs by reducing the need for businesses to lay off their workers.

It is reasoned that wage reduction in place of retrenchment benefits not only workers, who are able to retain their jobs and hence avoid periods of income loss, but also employers, who can retain experienced employees who will inevitably be needed when the economic situation improves. In contrast, laying off employees would mean additional training costs when businesses pick up again.

Most recently, in 2020, the NWC reconvened mid-cycle in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, to draft a set of Supplementary Guidelines which recommended temporary wage cuts to the extent necessary to minimise retrenchments, preserve critical capabilities and support business restructuring (more information in Tripartism and Industrial Relations).

Quantitative vs qualitative wage guidelines

Regarding wage adjustments, the NWC has traditionally provided two types of guidance – what it refers to as “quantitative” and “qualitative” guidelines.

Quantitative guidelines are those that recommend wage adjustments in numerical terms, usually percentages of current wages. These are given either as flat rates (e.g. 8%) or as ranges (e.g. 2% to 6%), or as absolute dollar ranges (e.g. $50-$70.)

Compared to flat rates, quantitative ranges offer more flexibility to businesses but introduce complexity because labour representatives need to bargain directly with business owners on actual wage adjustments. Issuing quantitative wage guidelines in absolute dollar amounts allows the NWC to target wage improvements at employees at the lower end of the wage spectrum (for whom wage increases in percentage terms could mean very small dollar amounts).

Qualitative guidelines are those couched in descriptive terms without the use of numbers. For example, the NWC’s 1994 wage guidelines did not put specific numbers to its recommended wage increments, but instead reminded businesses that wage increases should “lag behind productivity growth rates,” and that “[v]ariable payment should reflect closely the performance of the company”.

Qualitative wage guidelines offer employers the most flexibility, but can be most complex to implement, since parties to wage negotiation may disagree on the interpretation of key words or phrases.

The NWC’s stance on whether to issue quantitative or qualitative guidelines, or use them in combination, has shifted over the years. Each approach has its merits and shortcomings. Single absolute figures are simple to understand and implement, but not flexible enough to cover all business contexts.

From its founding in 1972 to 1977, the NWC opted to issue quantitative wage guidelines for simplicity. Between 1978 and 1985, the NWC adopted a mix of approaches, sometimes combining absolute dollar amounts with fixed percentages or ranges, which gave employers more flexibility to decide on actual wage adjustments. Responding to the recession in 1985, the NWC recommended “wage standstill” in April 1986 and later revised its guidance to “severe wage restraint” in December 1986. The latter was repeated in the 1987 guidelines.

In 2012, the NWC revived the practice of issuing quantitative wage guidelines. However, these new quantitative wage recommendations were targeted at lower-wage employees, for whom wage increases in percentage terms could translate to very small dollar amounts. This allows their wages to grow faster and narrow the gap with the median. Leading up to 2012, widening income inequality in Singapore and the plight of lower-wage employees had become a national concern. The salaries of lower-wage employees had lagged the rest of Singapore’s workforce in the prior decade because Singapore had imported large numbers of migrant workers – mostly deployed in lower-wage occupations – to support its economic growth. For example, between 1996 and 2007, the median monthly wages for cleaners and labourers sank from $860 to $600 as the number of migrant workers in these jobs grew.

Following the recommendations of the Tripartite Workgroup on Lower-Wage Workers, the NWC has issued a quantitative Range of Progressive Wage Growth for lower-wage workers since 2021. This includes both a percentage range and an absolute dollar range (e.g. in 2023, the range issued was 5.5%-7.5% and $85-$105). This range provides flexibility for businesses based on their performance, recommending employers facing economic difficulties to provide wage increases at the lower bound of the range.

Lim Swee Say, Secretary-General of the NTUC (2007 to 2015) and Minister for Manpower (2015 to 2018), shares that one deliberation in switching between quantitative and qualitative guidelines had to do with protecting low-wage workers:

Koh Juan Kiat, Executive Director of SNEF (1995 to 2020), recounts how employers made the transition towards quantum wage increases specifically for low-wage workers:

“I think for a long time, the NWC had in fact recommended that companies implement the NWC wage recommendations by converting the wage adjustment into a quantum and percentage wage increase for low-wage workers. But the feedback from our members and employers at large was that it was difficult to implement and not many companies implemented this because they seemed to prefer easier methods of either giving a flat quantum or a percentage wage increase… But I think this did not do enough to raise the wages of the bottom 10% [and] 20%. So, I think in 2012, [with] the growing number of low-wage workers, the tripartite partners came together and discussed how the NWC could make a difference to raising the wage levels of the low-wage workers. Initially companies with a large number of low-wage workers were quite resistant to this suggestion because it would mean a higher overall wage cost for them. To companies employing a few low-wage workers, it would be an easier way to implement the NWC recommendation and the wage cost increase would not be so significant.

But I think we managed to win over the larger companies because I think it was needed in order to help them to retain such workers. Because if such workers find that their wages were not rising fast enough vis-a-vis other segments of workers in the company, then they will make a run for other companies. So, it was timely that this suggestion was made because I think it helped the larger companies to retain their low-wage workers. At the same time, [there were] many retraining and reskilling programmes for the low-wage workers, especially with the formation of the Workforce Development Agency… I think it also spurred a work redesign because in order to lift the wages of low-wage workers and to pay them a quantum wage increase, which translates to a higher percentage in most cases in relation to the wage recommendations… the companies have to raise the productivity of the jobs.”

For decades, the NWC has forged agreement among employers, unions and the government on wage-related matters. Outside of the NWC, a tripartite approach has also been adopted to resolve other contemporary labour matters, such as initiatives to support women rejoining the workforce; re-employment of older workers; and work-life harmony.

For instance, a Tripartite Committee on Work-Life Strategy has been involved in promoting work-life harmony in Singapore. More recently, the tripartite partners launched an Alliance for Action on Work-Life Harmony in February 2021, with tripartite partners facilitating several citizen engagement sessions to discuss various work-life practices and rally participants to develop their own initiatives to develop work-life harmony.

Click here to read the case study “Tripartism in Wage Setting and Wage Flexibility, a Singapore Case Study”.