In September, a movement in New York called Occupy Wall Street to protest against the excesses that brought about the Great Financial Crisis, gathered pace and went viral, reaching many corners of the world.

In an interview with Salon.net on 4 October, the originators of the movement, Vancouverbased Adbusters, noted a culture clash behind the financial crisis. The social movement, originally targeted at its 90,000 supporters, has evolved into a global phenomenon largely focused on unequal relationships in societies. Now, it has grown beyond Wall Street into a broader “Occupy” movement as various countries adapted the strategy to air their grievances. Social media, facilitated by rapid technological change, has amplified the sense of injustice over rising inequality.

This was the backdrop to a LKY School of Public Policy Roundtable entitled “Rising Asia, Growing Inequality” on 30 September, planned weeks ahead, where T.N. Srinivasan, Yong Pung How Chair Professor at the School, sparked a lively debate with a question from the floor on the nature of inequality. One should examine the impact of wealth acquired unfairly, he said, returning to a theme that resonated with the audience. “Are we focusing too much on inequality without discussing the fairness in bringing it about?” he asked.

One also has to distinguish between shortterm and long-term inequality, and between the notion of inequality increasing at the start of globalisation versus the idea of it being a feature of globalisation, Srinivasan said.

Perceptions of inequality

We have witnessed “an attitudinal change” towards inequality, said Professor Kishore Mahbubani, Dean of the LKY School. As the US and Europe grapple with slowing economic growth and potential recession, “inequality is becoming a big theme in the West”, not just in developing countries, said Mr. Gideon Rachman, chief foreign affairs columnist of The Financial Times.

Rachman highlighted a perception that “inequality in the West comes from the rise of Asia due to downward pressures on wages of the unskilled”, as globalisation encouraged employers to scour the world for lower wages, hollowing developed Western economies. China is their favourite whipping boy, he noted. But many neglect to give China credit as her flood of cheap exports have lifted generations out of poverty by giving them access to goods and services hitherto unaffordable, he said, citing examples of Africans using cheap made-in- China hand phones to improve rural communications, evaluating global commodity prices to reduce the prohibitive costs of brokers, and facilitating mobile banking.

“People can tolerate rising inequality at the point where everybody was being a little bit better off,” Rachman said. It is when the wealth disparity widens to a point where people feel injustice that problems arise, to the extent of toppling long-serving governments, the panel agreed.

Even in prospering countries such as Singapore and Malaysia, resentment is rising, said Mr. Karim Raslan, a writer and consultant based in Indonesia and Malaysia. Aided by social media, “we see what the rich and powerful are doing and we are not happy. It (equality) is not just a product of societies going through a painful recession. You see it in periods of growth.”

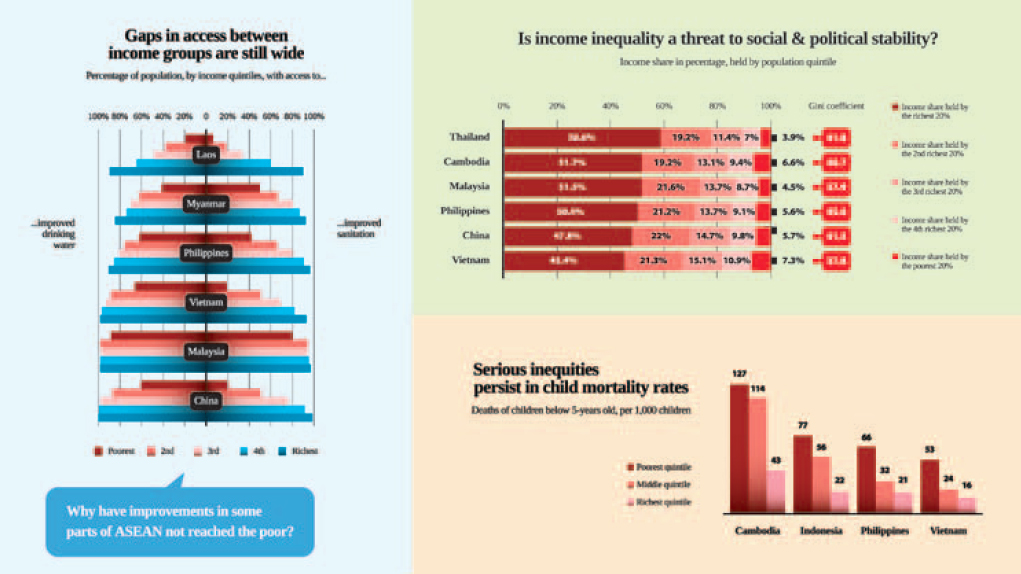

As growth slows and economic troubles mount, “people are falling at the bottom” even in developing countries where there has been extraordinary growth, deepening inequality, said Dr. Judith Rodin, President of the Rockefeller Foundation, which supports the Asian Trends Monitoring programme at the School. Governments cannot merely blame inequality on outsourcing and lower costs that comes with globalisation, but should address structural imbalances, she said.

Structural limitations

Indonesia, which underwent dramatic economic re-modelling after the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis, is a case in point, said Dr. Anies Baswedan, President of Paramadina University and one of Indonesia’s leading public intellectuals. Southeast Asia’s largest economy managed to reduce poverty in the early post- Suharto years of restructuring but witnessed a widening gap between rich and poor as easy credit created hot capital flows.

He identified the developmental gap between the urban centre and rural society as a structural problem impeding fair growth and wealth distribution, and recommended a review of the education system. “The economy is developed as an urban-rural model,” he said. “Our education system is designed to supply urban life”, exposing rural societies to structural deficiencies, he added.

“There needs to be some justice in economic growth,” said Senator Ton Nu Thi Ninh, President, Founding Committee of Tri Viet University, Vietnam. People do not resent the wealthy as much as those who obtained wealth through corrupt means, she noted. Echoing the anger behind the Arab Spring and the frustrations underpinning the nascent Occupy movement, Raslan denounced leadership where socio-economic capital is unfairly used for personal economic gain.

One lesson from the West in dealing with inequality lies in punishment for graft, Rachman noted. “The US and Europe still have an expectation that those who are corrupt and break the law will end up in jail.” This recourse to the law provides an important valve for societal anger. In Asia, there is a perception not only of inequality but of having no legal recourse, he said.

The value of education

“Inequality matters now compared to 40 years ago because we were more equal as we were all poor,” Baswedan said. “The challenge in the long run is to ensure everyone is moving up the ladder.’’

“Access to education is key” to mould people’s expectations of government services, he said, so that they expect more public service, and thus change is driven by demands from denizens, rather than dictated by the supply set by governments.

Inequality can in part be addressed by maintaining a “reasonable balance” between state and market forces to generate infrastructure for growth and thereby, services to provide for the fair distribution of wealth to alleviate poverty, said Professor Fu Jun, Executive Dean of Peking University School of Government.

China, the world’s third-largest economy, is grappling with the issue of achieving this balance and what it means for China and the world, he said.

Globalisation should be about the movement of three forms of capital – physical, human and social, Fu said. “In manufacturing, China has neglected human capital,” he said. “Labour is used instrumentally, neglecting aspects of human capital such as education.” And as peasants move to cities, workers lack the support they received in rural areas, which in turn “depresses the income” and exacerbates inequality, he said. Governments must also improve taxation processes to be able to fund future improvements and achieve the balance between state and market, he said.

In Vietnam’s case, public services such as education and health fell behind amid development, Ton said. “Without clear rules of engagement and a division of roles between the state and market, the savage market wins all the time”, resulting in the worst outcome for the country’s public hospitals and public state-owned schools, she said. “When it comes to the provision of human services, a proper analysis is needed before opening up to market forces.”

In Indonesia, infrastructure building is largely focused on the western islands of the archipelago, Baswedan said. “When we talk about inequality, there is inequality in terms of income but also in terms of geography, which sets us apart in ASEAN. It’s not just between urban or rural, educated or not educated, working or not working, but those who happen to live in the remote areas across the archipelago, so a different strategy must be adopted.”

Decentralisation in the past decade has both accelerated the provision of services and spread corruption in local institutions, he noted. Eradicating corruption and enforcing the rule of law is key, he reiterated.

Health and equality

On the matter of health and inequality, the findings of Asian Trends Monitoring provoked robust discussion from the panel. While Vietnam and Malaysia share a similar life expectancy of 64 years, the latter’s rate of obesity has more than quadrupled (45 per cent versus 10 per cent for Vietnam) and it has the worst indicator for diabetes among the ASEAN countries, prompting Raslan to urge the government to intervene more by controlling subsidies for sugar production.

Vietnam also shines in terms of its low rate of maternal deaths, ATM data showed. Ton provided a heartening statistic, noting that coverage of health services is countrywide, resulting in about 95 per cent of births being attended by trained health workers. About 86 per cent of Vietnamese women make pre-natal visits, while improved access to clean water, sanitation and road networks has helped reduce mortality rates, Ton said, underscoring the importance of infrastructure to public services. “The doctors are able to come to your aid easily” as a result of good roads, reducing maternal deaths, she said.

Vietnam’s model is a shining light for other developing countries in the region, where the gap between rural and urban women in terms of access to skilled care during childbirth remains wide, particularly in Laos, Cambodia, the Philippines and Indonesia, according to ATM data.

Indonesians have also become dependent on one crop, rice, for protein, Baswedan noted, raising concerns over the potential for widening inequality when availability is threatened. The impact of climate change should be considered when formulating policies that address inequalities, Rodin said.

In today’s world, there are challenges of inequality for both developing and developed countries, and in an era of globalisation, policies have a greater impact than decision makers may have originally calibrated.

Claire Leow (claireleow@nus.edu.sg) is senior manager for research and dissemination at the LKY School.