We’ve all heard heart-wrenching stories about animals and plastic pollution. A sea turtle had a

straw up its nose. A young sperm whale washed up dead in Spain with

64 pounds of garbage (including plastic bags and a drum) ingested. The endangered Albatrosses are

feeding their chicks plastic because they mistake them for squid and cuttlefish at the surface of the ocean.

Animals are suffering — and dying — at the hands of humans. Yet, many people around the world are still using plastics very easily. Worse, these are not being disposed of properly. Already, there are

five floating islands of garbage — mostly plastic — in the world’s seas, and the largest is about

three times the size of France.

Why are we so poor in managing plastic waste?

Asia’s rapid economic growth The brunt of contributors to the plastic problem today is the developing countries of Asia, says

Visiting Professor Vinod Thomas from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, because their economic growth has far outstripped their practices for waste management and environmental conservation.

“The region has been growing about twice the rate of what we saw with the industrial countries about 100 years ago — three times that in the case of China. The pace of resource exploitation has surpassed both the technological advancement and socio-psychological mindset needed for these countries to clean up as they go,” Professor Thomas says.

It is of no surprise that the

2017 Ocean Conservancy report found that “Indonesia, China, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam dump more plastic into the oceans than the rest of the world combined.”

Racing against time That is where the problem lies, says Prof Thomas. “The industrial countries could run in tandem their technological solutions and changes in incentives and mindsets with their economic boom spread over a century. But we don’t have the luxury of time now.”

Every year, humans produce about 300 million tonnes of plastic waste, and about 9% is ever recycled, reported the

United Nations Environment Programme. The majority (79%) ends up in landfills, dumps, or the natural environment.

In fact, as much as eight million tonnes of plastic reaches the world’s oceans every year. “If current trends continue, our oceans could contain more plastic than fish by 2050,” the agency said.

With time ticking away, we will need to “see dramatic change happen within the next 10 to 25 years,” informs Prof Thomas. There needs to be a powerful transition to how we manage plastic especially in Asia, where everything will reduced, reused and recycled.

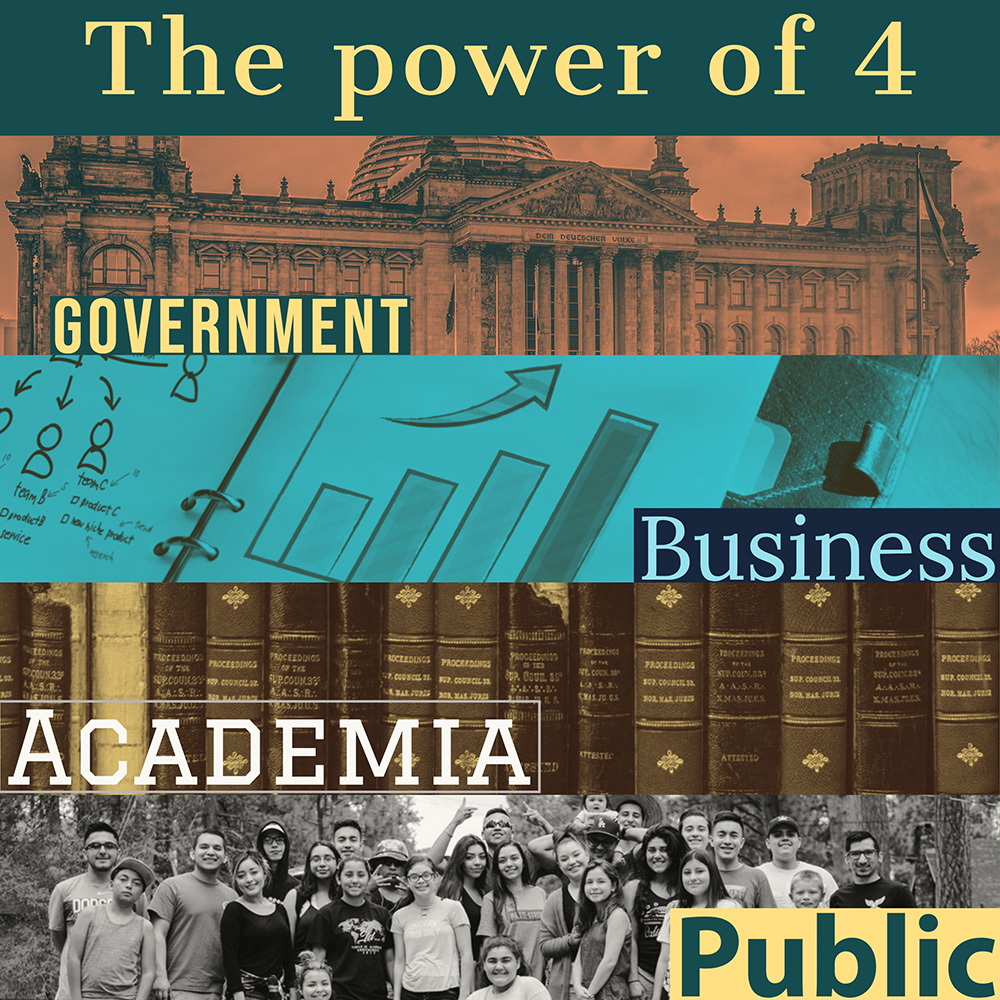

The power of four It will be hard, and the next 10 years will be particularly important, but Prof Thomas thinks the region has hope if society’s four sectors — government, business, academic communities, and the public — can work together. By themselves, change is unlikely to happen fast.

Governments to initiate mindset change

Governments to initiate mindset change Government regulations against the use of single-use plastics for example, could kickstart and expedite a change in people’s mindsets and reliance on plastic. For example, as of 1 January 2019, South Korea has

banned the use of disposable plastic bags by major supermarkets and retailers nationwide.

The 2,000 outlets of major discount chains and 11,000 supermarkets with sales floor spaces of 165 sq m or more are required to offer customers only recyclable containers, cloth shopping bags or paper bags, or be subject to fines of up to three million won (US$2,700).

Similar bans have been implemented across some countries in Africa, some states in India, and

Bogor city in Indonesia. But just the bans alone are not enough; governments have to be resilient in implementing it and carrying out the necessary fines to drive the message through.

That is where educational campaigns come in to help complement these regulations. “Changing motivations take time, so educating the public should go hand in hand with regulations, so they understand the ‘why’ behind using less plastic,” Prof Thomas says.

Role of the business and academic sectors Businesses can also partner with the academic community to make use of new innovative and alternative plastic solutions, and encourage recycling of plastic waste. Scientists at the National University of Singapore (NUS) can now

convert PET (polyethylene terephthalate) bottles into aerogel, a highly insulating and absorbent material and one of the lightest and most porous known to man.

This PET aerogel can be surface treated to line fire-retardant coats and absorption masks for firefighters, as heat and sound insulation material in buildings, or as a ‘super absorbent’ material to clean up oil spills — it can absorb up to seven times the amount of oil than existing commercial sorbents.

NUS researchers have converted plastic bottles to aerogel, a material which can be used to line fire-retardant coats. Photo credit: National University of Singapore.

NUS researchers have converted plastic bottles to aerogel, a material which can be used to line fire-retardant coats. Photo credit: National University of Singapore. These applications are currently made using silica aerogel, which costs about S$40 (US$30) a sheet. In contrast, PET aerogel is literally produced from PET bottles, with one bottle producing one A4 sheet, at a lower cost and substantially shorter production time. PET aerogel is perfectly commercially viable for businesses to use, and the business sector would eagerly commercialise other academic innovations too, if they have real-world benefits.

But we should not fall into the trap of depending on these innovations, and forgetting about the real message when it comes to plastic, says Professor Nhan Phan-Thien, who co-led the PET aerogel project at NUS. “The innovation is a large step forward, but it only takes care of a small proportion of the problem. It is not a permanent solution; it's only temporary. A means to delay the end, and to lengthen the life cycle of plastic.”

The other lead for the project, Associate Professor Hai M. Duong, asserts: “The real solution to the plastic waste problem would be to tackle the root of it all - educating the general public about the real costs of recycling and single-use plastic. Zero waste has to happen at the beginning.”

It all comes down to Man The public is therefore the most important party in this whole equation for managing plastics waste. Ultimately, we are the ones using the plastic, disposing of it, and contributing to the

environmental damage if this is mismanaged. The mindset about using the material has to change in order to efficiently manage plastic waste.

Those in this region particularly “need to catch up within the next 25 years to not only leave a more sustainable planet, but also simply to sustain the growth rate and welfare improvements we have so far,” stresses Prof Thomas.

“If we’re looking at business at usual, it might take 50 to 75 years for these countries to work themselves out, but by then it’d be too late. The garbage situation would have destroyed our lives and livelihoods,” he says.

(Photo:

Ikhlasul Amal)