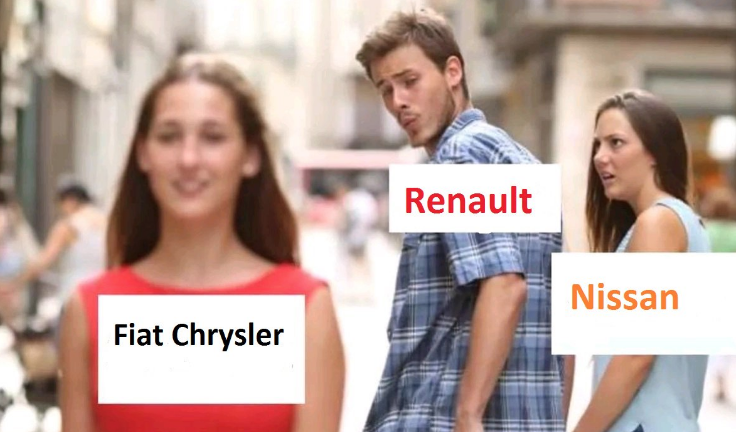

“Distracted boyfriend” meme explaining potential corporate merger. @Malavtweets

“Distracted boyfriend” meme explaining potential corporate merger. @Malavtweets

In May 2019, the New York Times ran a popular meme on the front page of its business section. The ‘distracted boyfriend’ meme, which went viral in 2017, was used to explain a potential merger between two automakers and its presence in a major newspaper signified the sheer ubiquity of internet culture.

Once a millennial tool of digital subculture, memes are now being integrated into traditional media and daily conversations. Their profound impact on how information is disseminated and absorbed by the general public has been acknowledged by corporates and governments, leading to extensive study on the potential for manipulation and weaponisation.

What’s in a meme?

Richard Dawkins meme

Richard Dawkins meme

The term meme was first mentioned in 1976 by biologist Richard Dawkins, who described it as an idea, belief or behavioural pattern that, like genes, can propagate amongst individuals. Memetics is the study of how cultural information, is transmitted in this manner. When applied to the models of internet humour that we call memes, memetics explores how these graphics spread from niche websites such as 4chan to mainstream social media platforms.

Exactly how memes impact social, commercial and political narratives was the topic of a panel discussion held by Global-is-Asian on November 22, 2019 as part of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy’s inaugural Festival of Ideas.

As modes of digital communication evolve, images are now merging seamlessly with words, said Simon Kearney, moderator of the panel and CEO of Singapore-based content agency Click2View.

In a time of rapid digitalisation, shortening attention spans, social activism and the rising threat of fake news, “the conversation about memes is definitely a timely one,” added panellist Nicholas Fang, Director of Security and Global Affairs at the Singapore Institute of International Affairs.

The politicisation of memes

Deployed by the likes of US President Donald Trump and trolls hired by the Russian government, memes have become powerful instruments for politicians looking to influence voters.

“Meme culture is one of the defining movements of our age and from a public policy point of view, needs to be seen in the prism of its influence over large numbers of people as a rallying point for opinions, beliefs, and often disenfranchised communities,” Kearney said during the panel session.

He noted how Trump invited meme artists to a social media summit held at the White House in July—an event that critics said was aimed at hyping up the president’s online supporters.

One of the key reasons why memes are popular amongst leaders is their social impact, according to Fang. Whilst memes can be universal, many are effective because they are localised. They can be “cultural snapshots that speak to both broad and specific audience groups within [a] particular society,” he explained.

In a way, memes are actually “the political cartoons of today that we used to see in the pre-digital age,” he continued.

The subtlety of memes is another major draw for politicians. The format allows for a very indirect expression of opinion or criticism of opponents, Fang commented. The understated nature also works on audiences, he noted: “A political message may already be seated in your brain before you even realise that you were laughing at the joke.”

When you laugh at something, you’re somewhat accepting the message, echoed Dr Natalie Pang, Senior Research Fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Institute of Policy Studies.

Dr Pang, who is also a senior lecturer of communications and new media at the university, has been examining how memes and other pop culture content are weaponised on instant messaging platforms.

“Memes can be used in what we call ‘othering’,” she said on the panel, alluding to prejudice against individuals of different racial, ideological or sexual identities. Othering has social consequences such as segregation, and is also crucial to understanding how falsehoods take root and are used to manipulate opinions in different social groups. Countries like Indonesia have recently shut down WhatsApp to prevent such manipulation and amplification of divides between groups.

In studying group chats on popular messaging apps such as WhatsApp and Telegram, Dr Pang observed social behaviour that enabled controversial memes to flourish. In group chats, people often hesitate to call out a racist or hate-provoking meme, often because of the power structures and being seen as a spoilsport because of dominant opinions in the group, she said.

How companies use memes

Beyond the political realm, memes boast widespread benefits for companies looking to build a loyal customer base.

“There are four key reasons why companies are increasingly using memes,” Fang said: “It’s inexpensive, it takes a little bit of time, it takes a little bit of creativity and it builds a sense of community for the brand.”

If companies utilise memes in their public relation campaigns, it creates the idea of both customers and brand being “in on the same joke,” Fang explained. Memes are typically based on current events or trends so their usage also creates brand relevance, showing consumers that the company is up-to-date with society, he continued.

That’s why it’s important for brands to follow memes because they are “a good source of social media intelligence,” he remarked. Memes “give you a sense of the zeitgeist, what people are talking about and more importantly, how they're talking about it or how they view particular issues.”

Since memes are typically quickly understood and easy to share, that also “allows the activation of the public to become advocates for the brand, whether they know it or not,” Fang added.

The importance of fact checking

Whether memes are used for business or politics, they can be inherently problematic and require fact-checking, experts at the panel agreed.

Information disseminated by memes aren’t facts but rather, social commentaries and opinions. That could help facilitate disinformation, especially if individuals don’t take pains to diversify their sources of media.

“One issue that we came across in our project was just how people moderate conversations, or how they fact-check,” Dr Pang said. In some group networks, there's not much fact-checking because it all depends on the administrators, she flagged. Rather than raise any concerns on a group chat, people are more likely to discuss serious matters in one-on-one chats, she said.

Contemporary tools such as data mining also have limited benefits, Dr Pang pointed out. “Mining tools are useful in terms of scraping, but not so much in terms of analysis,” she said, adding how these tools aren’t good at picking up subtle social or political satire.

Tread carefully

With memes now an inevitable component of pop culture, their cultural clout cannot be ignored, the panel concluded.

A key feature of meme creation is “wilful immaturity,” Click2View’s Kearney described. But even unsophisticated humour has the power to drive markets, he explained. The “OK boomer” meme, which pokes fun at baby boomers and went viral this year, is now so popular that it even has its own physical merchandise, Kearney said.

The meme has become the “perfect” instrument to relay emotions at a time of short attention spans, Fang added.

Memes have the power to spark social action but they also reductionist in nature, Dr Pang chimed in. Simplifying complicated discourse into a pair of images may lead to incomplete comprehension of issues that impact society, she said.

That’s why it’s important for people to actually discuss the issues behind memes, Dr Pang continued.

The only way to counter memes is to create “more real conversations, more human conversations offline rather than online,” mirrored Fang.

(Photo: Sebastiaan ter Burg)