When migrants set up businesses in home countries, the ripple effects on the local economy and employment can be advantageous for both remittance and non-remittance receiving households. Nicola Pocock examines why.

When migrants set up businesses in home countries, the ripple effects on the local economy and employment can be advantageous for both remittance and non-remittance receiving households. Nicola Pocock examines why.

Forty-year-old Jean is a formidable entrepreneur, as demonstrated by the five businesses she owns in the Philippines. These include a riceretailing business, food supplement wholesaling and a recycling business. The average monthly profit of the businesses combined is S$2,000 (US$1,582), enough to cover her extended family’s needs. “Now, I’m starting to build a resort, which will have two houses and a swimming pool”. Jean has worked in Singapore as a domestic worker for the past 25 years. Having learnt the importance of saving for the future, she has put aside money throughout her time here and continually reinvested profits into businesses managed back home by family members. Growth and financial sustainability are her main goals— “I want to be able to go back to the Philippines without worrying about money”.

Transient Workers Count 2 (TWC2), a migrant rights advocacy organisation, estimates that nearly one million foreign workers in Singapore earn low wages, and are employed in construction, shipping, sanitation services, manufacturing and domestic work. Manual workers do not enjoy a minimum wage, and neither do the 201,000 domestic workers in Singapore, of whom only 12 per cent have a weekly day off, according to TWC2. Amid the debate about migrant rights in the city-state, remittances offer a positive story in the maelstrom.

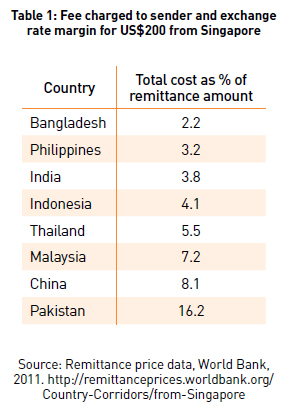

A study by the Asian Development Bank estimated that migrant workers from the three main sources of labour—the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia—remitted a combined total of US$506,625,270 from Singapore in 2005. The large number of migrants in Singapore and competition between remittance providers has helped to drive down the cost of sending money home, especially to Bangladesh and the Philippines. Remittance fees between Singapore and Bangladesh are actually the cheapest in the world, and those between Singapore and the Philippines the fourth cheapest globally.

A large body of literature on remittances at the micro-level reveals numerous positive impacts, including the increased ability of remittancereceiving families to purchase land and durable assets, invest in education and make other purchases that stimulate the local economy, which includes non-migrant households. As migration and remittances expert Hein de Haas asserts, when a remittance-receiving family decides to construct a house, the local construction industry experiences a positive effect on wages, prices and employment (Hein da Haas 2007, Remittances, Migration and Social Development: a conceptual review of the literature, UNRISD Social Policy and Development Programme Paper no. 34).

But, because international migrants tend to be from comparatively wealthier families, the direct beneficiaries of remittances are also not the poorest community members.

These are reasons why migrant entrepreneurship— migrants in countries like Singapore saving and remitting money to family members in the Philippines, Indonesia and Bangladesh to start businesses—is an important phenomenon. When migrants set up businesses in home countries, the ripple effects on the local economy and employment can be advantageous for both remittance and non-remittance receiving households. Jean employs six people, two of whom are not family members in her native village.

Fostering savings and entrepreneurship is the explicit goal of aidha, a micro-business school for migrant workers, especially domestic workers, in Singapore. Set up in 2006, aidha provides financial literacy and entrepreneurship training to migrant domestic workers via an integrated curriculum that includes savings clubs and hands-on business experience via Project Makan, a restaurant management training program.

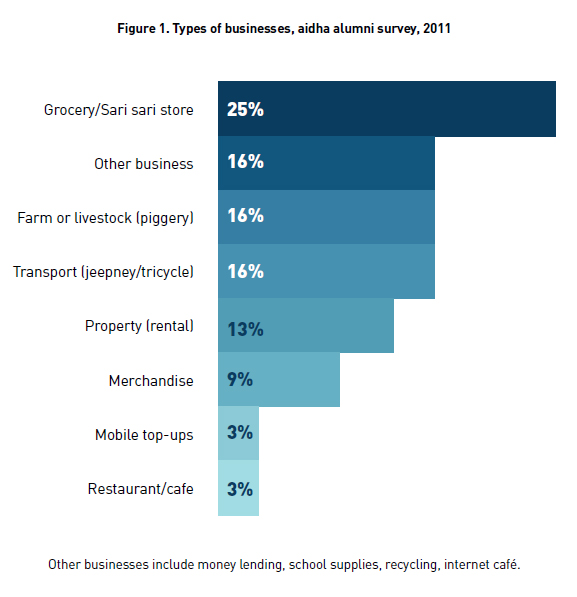

A recent survey with 52 alumni (a third of aidha’s graduates) revealed that more than 66 per cent have invested their savings in two or more income-generating assets whilst working abroad, the most popular being rearing of small animals, provision of transport services and land for business purposes. Of the sample, 39 per cent are currently business owners, with an average monthly profit per person of S$374 from various business ventures. For one in three business owners, this is enough to support most or all of their household’s monthly expenses. Perhaps unsurprisingly, 100 per cent of these businesses were financed partly from savings, followed by employer loans and profit from former businesses.

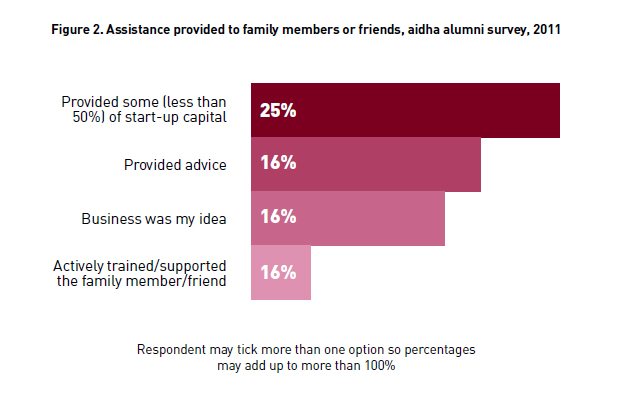

Furthermore, migrants help family members or friends back home to set up their own businesses. Half of the alumni surveyed by aidha had provided some kind of assistance, with 67 per cent providing some of the startup capital required.

By fostering migrant entrepreneurship in both source and destination countries, remittances and micro-businesses can be leveraged for local development. Succeeding as an entrepreneur can also provide migrants with an alternative to the cyclical pattern of migration so common in the Southeast Asia region.

Migrant entrepreneurship can be facilitated by designing financial products in host and source countries that help migrants to save and invest, as well as by encouraging institutional investment in micro-enterprises run by migrants remotely or by their families.

In Singapore, the low cost of sending money home is an added advantage. But migrants arguably face difficulties in accessing savings products suited to their needs, particularly at local banks. New account openers must provide a S$500 deposit, a substantial sum for many migrants. Singapore banks often restrict access by occupation, with the most widely used bank, POSB, allowing those with work permits to open an account but not those with domestic worker permits to do the same. Some domestic workers have been refused accounts at the branch level, even when this is not explicit bank policy. Migrants face prejudice at the branch level—this has to change. If the city-state prides itself as being a financial services centre, and if migration is expected to be temporary, as indicated by the government’s emphasis on guest worker programs, then surely enabling migrants to access savings products is a win-win solution, if not a basic right?

Programmes like aidha’s that offer training in essential business skills can help migrants to set up successful businesses in home countries. Singapore should be encouraging employers of migrant workers as well as including domestic workers and those in other sectors, to help employees to conceive and plan for their futures by investing in their training and development— just as they might for their local employees.

Offering migrants access to financial services and business education could enable them to take a proactive role in shaping their own futures, rather than be subject to structural constraints that provoke them to seek employment abroad in the first place.

Nicola Pocock is a Research Associate with Asian Trends Monitoring Bulletin and the cohead of research at aidha, a micro business school for migrant workers in Singapore.