What do Asians think about the crisis that is unfolding thousands of miles away in Ukraine? The answer was: whose narrative do you believe?

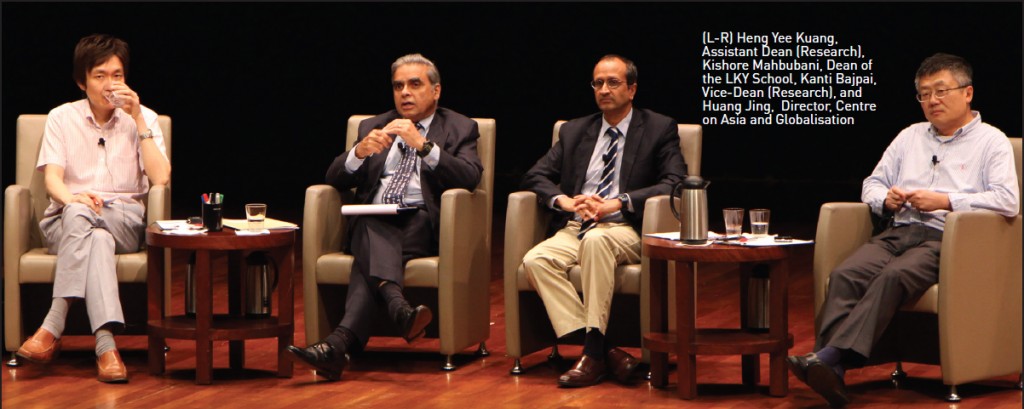

A panel of four professors – Kishore Mahbubani, Kanti Bajpai, Huang Jing and Heng Yee Kuang – set out to provide some answers during the Dean’s Lecture Series on The Ukraine Crisis: Asia’s Reactions, on 20 March 2014. The discussion highlighted many interesting – and often unexpected – insights both from the panellists and audience.

Dean Kishore Mahbubani opened the discussion by commenting that events in Russia had been perceived and expressed differently in Russia and the West.

The Western narrative, which dominated the media, was clear: people rose up, got rid of a bad ruler, and the world should welcome what happened in Ukraine.

The Russian narrative however, was quite different. At the end of the Cold War, the Russians had believed that NATO would not expand eastwards – and hence were shocked when NATO crept to Eastern Europe.

When Crimea fell to Western forces, their naval base and only warm-water port was threatened. In an effort to hold back NATO at their doorstep, the Russians felt that they had to get back Crimea. He predicted that the Russians would go no further, and that after a few nominal sanctions, the West would accept Russia’s occupation of Crimea.

Huang Jing explained that in the context of the new relationship between Washington and Beijing and their mutual interests, China should have supported the US position and condemned Russian intervention.

However, China refused to do so for three reasons. First, China’s long-term principle was non-intervention in other countries’ internal affairs. The United States had violated this principle by mobilising opposition against a democratically elected government and president. Second, China wanted to build a good relationship with Russia for security, diplomatic and economic reasons, and also to gain Russia’s support.

Third, the West’s position was a clear case of double standards when compared to Kosovo in 2008, since Kosovo’s independence had been illegal and against international law, but the West had taken no action to present this. China’s abstention in the Security Council, although ostensibly neutral, had been a sign of support to Russia. This was why Putin had thanked the Chinese people for their support.

Kanti Bajpai discussed Indian official statements with regard to the Ukraine crisis. Although the first reaction in the Indian press had been supportive, the language used by India’s Foreign Minister, Shivshankar Menon, was nuanced, “There are legitimate Russian and other interests,” he had said.

India made two other key points: first, India sought a peaceful resolution and was the first major power to come out against sanctions; second, India would support a Ukranian resolution stressing territorial integrity but not a resolution condemning Russia.

Bajpai noted, however, that India was uncomfortable with the situation. Because India had territorial problems with Pakistan (over Kashmir) and China, India was uncomfortable with the idea that Russia had taken over Crimean territory because 98 per cent of ethnic Russians wanted to join Russia. It was surprising, therefore, that India would come out pro-Russian.

However, there were many reasons why India did so. Russia was India’s biggest arms supplier, supplying 70 per cent of its weapons. Moreover, India had its eye on Russia’s huge energy supplies. Finally, India’s growing unhappiness with the United States also played a role. India’s nuclear deal with the US had gone sour; this was compounded with difficulties over a range of issues – with regard to Afghanistan and Pakistan, American complaints with Indian trade and investment policies, and even America’s shabby treatment of an Indian diplomat accused of mistreating her housekeeper.

Heng Yee Kuang discussed Japan’s reaction to the crisis. He pointed out that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was caught between his traditional G7 partners and Russia, which he termed “the only bright spot in Japan’s neighbouring diplomacy”.

Abe had held bilateral talks with Putin five times since taking office and was optimistic about his chances of signing a peace treaty with Russia. Abe had also attended the Sochi Olympic Games despite boycotts from many Western countries. Russia and Japan had just launched talks on defence and security relations. This was in sharp contrast to the cold relationships Abe had with South Korean and Chinese leaders.

Thus, the Ukraine crisis had come at a bad time for Japan. Because it opted to go along with its G7 partners and impose sanctions on Russia, Tokyo froze all talks on trade, military and investment with Russia. The Japanese industrial minister did not attend a recent Russo-Japanese investment forum because of the Ukraine issue, and the Japanese foreign minister declared, “We cannot overlook Russia’s attempt to change the status quo by force” – the same language Japan had used to oppose China’s position in the South China Sea. Japan feared that China might mimic Russia’s actions. Japan’s basic position was its insistence on upholding the rule of law in international relations, rather than supporting a powerbased order.

When Mahbubani asked the audience whether they supported the position of Russia or the West, an overwhelming number of participants raised their hands in support of Russia.

However, questions were raised surrounding the wisdom of Russia’s strategy, which Huang called a “rash” decision. Bajpai suggested that the decision to intervene in Crimea might have been taken impulsively, due to Russia’s “sense of victimhood” and “inferiority complex”.

Similarly, Heng argued that the Ukraine crisis provided a good case study for “decision-making under crisis”. Huang argued that Russia might be forced to look towards China and India as a result, and declared that the crisis was a “godsend” for China.

Mahbubani, however, argued that the West had pushed Russia into a corner that gave it no option. The discussion ended with the panellists discussing Margaret McMillan’s controversial argument: a century on from 1914, when a small crisis in an obscure part of Europe had led to WW1, dark clouds still hung over the region. Although Mahbubani was quick to argue that the present situation was different, the historical comparison left the audience with much food for thought on the changing perceptions of sovereignty and power in a world connected on so many levels.

Yvonne Guo is a PhD Candidate at the LKY School.