This article was first published in Nikkei Asian Review on 4 July 2018.

The poor now mostly have enough food, but need better clinics, schools and administrators

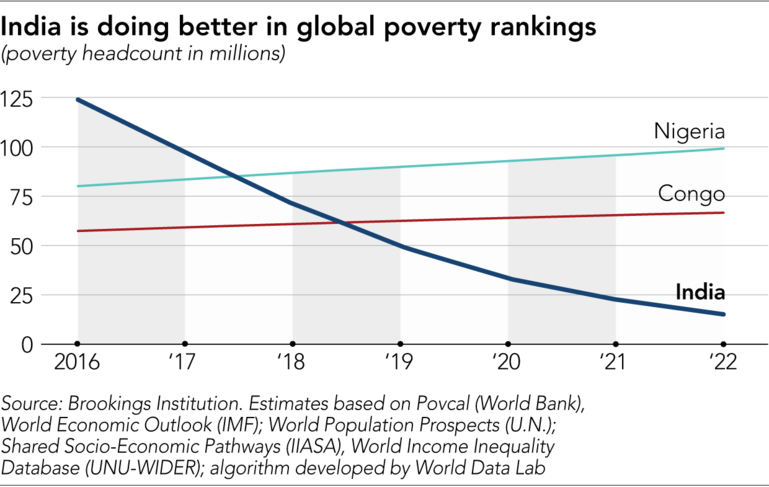

It is not often you see a chart that changes the way you look at Asia. The chart in question, which circulated online this week, shows India's unexpected recent progress curbing extreme poverty.

More importantly, it explains something important about India's changing development challenge, as it moves quickly to become a middle-income nation, rather than a poor one.

Drawing on new data from the World Bank, the chart in question,

published earlier this month by researchers at the Brookings Institution, shows the number of Indians living in poverty falling rapidly -- from 125 million in 2016 to around 75 million today, to 20 million in 2022, and then dropping to near zero not long after.

Here is the chart:

This is remarkable for a number of reasons.

First, it suggests India's success eliminating poverty has been even greater than many believed.

Center-right thinkers like economist Jagdish Bhagwati have long extolled India's poverty reduction record in the era since its economic reforms began in 1991. Yet India's record now looks even better than Bhagwati suggested.

As recently as 2016 the World Bank cited data showing that 270 million Indians still lived in poverty, meaning those living on less than $1.90 a day, a number agreed in 2015 as the minimum most people in poor countries would need for basic food, clothing, and shelter.

This shift is partly explained by methodological changes to the way poverty is measured. Even so, moving from 270 million to 75 million in less than a decade is impressive.

Second, the same Brookings data show that Nigeria has now overtaken India as home to the largest number of the world's extreme poor. As the chart illustrates, it will not be long before Congo pushes India into third spot.

All of this suggests that extreme poverty will soon be a largely African problem, with only small patches remaining around south and southeast Asia.

A mix of factors explain this remarkable shift. Some credit should go to India's previous Congress government, which introduced various state programs designed to help the very poorest.

Many of these have been pilloried for their inefficiency, notably the massive National Rural Employment Guarantee (NREGA) scheme, which gives basic menial jobs to anyone who wants one.

NREGA is expensive and wasteful: India's latest budget allowed 480 billion rupees ($7 billion) to the program in the fiscal year ending in March 2018. But latest evidence suggested it also provided employment to 51 million households in 2016, which surely helped reduce extreme poverty for many near the bread line.

Just as important as government intervention, however, is the trickle-down effect from India's decades of recent rapid economic growth. Average income per head in purchasing power parity terms has risen from $1,140 in 1991 to $6,490 in 2017, according to the World Bank, putting India firmly in the ranks of middle-income states.

Some caution is needed here. Many of those who have officially "escaped" poverty still live precarious and grim lives dogged by ignorance and disease. This is a group for whom slipping backward into absolute poverty often remains a major risk too.

In a deeper sense, India's progress raises a conundrum, because its impressive record of absolute poverty reduction looks rather less impressive when measured by fuller measures of human development. Progress on issues such as maternal health or child mortality has typically been better in less successful countries like Bangladesh or Nepal, a point made by Nobel laureate Amartya Sen.

Just as importantly, Indian inequality has rocketed over the last two decades, a point I make in my book "The Billionaire Raj," which is released this week. India's top 10% of earners now take 55% of national income each year, up from 32% in 1980. The bottom 50% have seen their share decline from 23% to 15%, with the very poorest doing worst of all.

India's poorest have benefited from the country's new economic model, but nothing like as much as the rich -- a trend which is likely to store up problems for the future, given that countries which start out their development with yawning inequality find it much harder to correct it later.

Still, absolute poverty reduction is genuinely worth celebrating. Many African nations can only dream of making rapid Indian-style progress.

Striking data such as these also underlines the extent to which our perceptions of India also now needs to change. In truth, large swathes of India already share more in common with the middle-income nations of Southeast Asia than they do with sub-Saharan Africa.

Official data say a third of Indians now live in cities although other estimates put the figure much higher. You can still see patches of grinding destitution if you go to fast-growing places such as Chennai or Hyderabad or Panjim (in Goa), but mostly you will see prosperous urban centers.

Even in the grimmest rural regions, the poverty-stricken India of old is fading away. Back in 2017 I took a trip to Uttar Pradesh, a giant but underdeveloped Indian state with a population of more than 200 million. The state remains one of India's most problematic regions, and especially so in the city of Gorakhpur, which remains a byword for criminality, disease and economic backwardness.

During the visit I spent a few days driving around this area, bouncing along potholed roads and visiting small villages. It would be fair to say that Gorakhpur remains a pretty miserable place to live.

Yet even here there were fewer signs of the dire problems of hunger and abject hardship that defined people's perceptions of India perhaps as recently as a decade ago. Young people generally went to school and found a basic job. They had mobile phones and modern clothes and lived in brick homes, not mud-walled huts.

At the same time, however, they often lacked reliable water and electricity supplies, while their streets had no sewerage or rubbish collection, and their politicians were comically corrupt, for instance taking government funds designated to build indoor toilets for the poor, and using it to build fancy houses for themselves.

Many residents suffered from preventable ill-health problems too -- Japanese encephalitis is rampant in the area -- because medical care was haphazard. Although almost everyone went to school, the education they received often was barely worth having.

"Indians are living behind their means" was how the Indian author and journalist Shekhar Gupta put it to me during that trip. "There was an old poverty where you did not have enough to eat. The new poverty is getting some development but not all, because municipal administration is weak."

As with many middle-income countries, India's fight against poverty needs now to focus less on the alleviation of extreme hardship. That battle is close to being won in large parts of the country. Instead, it needs to begin a new fight to build basic state capacity, providing decent government services and inexpensive forms of social security with can help its people build better lives.

Here, the contrast with the successful emerging economies of East Asia is again clear. Most of these managed first to produce dramatic reductions in poverty, but then also developed a more inclusive model of growth shepherded by a more competent state machine, which, crucially, emphasized universal education and healthcare. That is now India's challenge too.