Biodiversity supports all life and underpins all economic activity on Earth. According to the World Economic Forum, about US$44 trillion of global economic value generation – which is over half the world’s total GDP – is moderately or highly dependent on nature and the ecosystem services it provides (1). Yet human activity is causing biodiversity to decline at unprecedented rates, directly threatening livelihoods, economies and wellbeing whilst undermining nature’s ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions (2).

After decades of largely unsuccessful “fortress conservation” (3) – involving forceful exclusion of local communities from their customary lands to create protected areas – there is increasing realisation that local and Indigenous communities may in fact be the best stewards of their natural landscapes. Given that areas of critical biodiversity importance around the world are inhabited and used by Indigenous and local communities (4), their active participation in management is a key ingredient for success. Community-based approaches to conservation are thus considered essential for meeting global biodiversity (5) and climate change targets (6), while ensuring communities have the right to realise their livelihood aspirations.

By shifting the emphasis away from protected area conservation approaches, and cultivating community-based conservation as well, this can empower communities to decide and plan on what type of activities are carried out in their lands or waters. This can mean a significant difference in ensuring how to forge a more sustainable future for ecosystem services and biodiversity.

Conservation organisations worldwide are working with local and Indigenous communities to devolve local resource use and management rights to these communities, while supporting traditional systems of resource management - which are often aligned with biodiversity goals (4). Yet, despite widespread adoption of ‘community-based natural resource management’ (CBNRM) approaches, there is little understanding about what works and what does not work in CBNRM. This information is essential if CBNRM is to effectively deliver social, ecological and climate benefits.

This question was addressed in a

comprehensive national-level evaluation led by Dr Tanya O’Garra, Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Environment and Sustainability, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, together with co-authors from Fiji, the UK and the US, which was published in Nature Sustainability.

The study

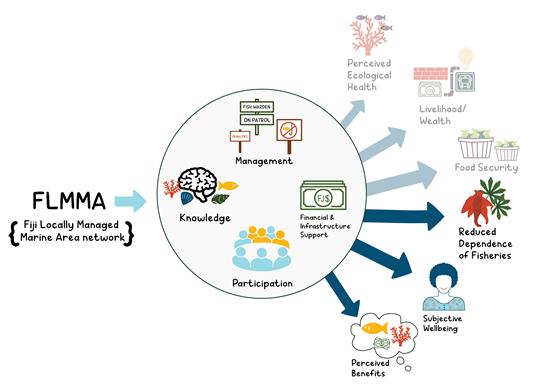

To evaluate what works and what doesn’t work in community-based management, the team chose to evaluate the Fijian locally managed marine areas (FLMMA) network, a national network of over 350 coastal villages aiming to improve fisheries management with support from partner organisations. ‘Locally managed marine areas’ (LMMAs) are a type of marine community-based management initiative found throughout Asia and the South Pacific, with Fiji having the most extensive network of LMMAs in the world. The team identified whether village engagement in the FLMMA network led to improvements in a range of desired conservation and social outcomes, and quantified the ‘mechanisms’ that are expected to deliver these outcomes.

To generate estimates of the causal impact of FLMMA on village outcomes, the team used ‘matching’ approaches to select non-FLMMA villages so that they were similar to LMMA villages at baseline. The purpose of doing this is to minimise the effect of ‘confounders’ which are factors that might influence both village participation in the FLMMA network and conservation outcomes. One example of a confounder in this case is size of resource to be managed – villages with larger fishing grounds may be more likely to join FLMMA – and the size of the fishing grounds may also affect how well their fisheries responds to management. Failure to control for the effects of confounders such as these can lead to incorrect assessments of impact.

Using key informant interview data from 78 FLMMA villages and 68 non-FLMMA villages selected using matching, the team found significant improvements in the mechanisms hypothesised to deliver conservation and social outcomes – including participation and knowledge, fisheries management, and financial and infrastructure support. Yet these improvements led to few tangible outcomes.

Illustration by Manini Bansal

These findings suggest that practitioners and communities working together in CBNRM projects may need to carefully evaluate and adapt the mechanisms and pathways through which they expect their efforts to generate impact.

An additional – and perhaps crucial finding – was that communities in which women were actively involved in management showed greater household wealth, food security and fish catch, regardless of whether the village belonged to the FLMMA network. This finding highlights a potential adaptation to existing efforts that might be implemented by practitioners and communities seeking to improve livelihood outcomes.

Next steps

For community-based conservation to contribute to global biodiversity and climate targets, CBNRM interventions must work at scale. This depends on the diffusion of CBNRM initiatives over space and time, and adaptation or tailoring of initiatives as they spread, to ensure effectiveness translates from one context to another. In addition to continued work on the mechanisms and impacts of locally managed marine areas in Fiji, members of the team will be conducting further research that will seek to explain and predict the diffusion and effectiveness dynamics of CBNRM as well as other conservation initiatives, to support scaling of effective conservation projects.

For more information, please contact Tanya O’Garra at

t.ogarra@nus.edu.sg.

References

1. https://www.weforum.org/press/2020/01/half-of-world-s-gdp-moderately-or-highly-dependent-on-nature-says-new-report/

2. https://www.ipbes.net/global-assessment

3. https://climate-diplomacy.org/magazine/conflict/fortress-conservation-heading-crisis-cant-come-soon-enough

4. Garnett, S. T. et al. A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nature Sustainability. 1, 369–374 (2018).

5. Gurney, G. G. et al. Biodiversity needs every tool in the box: use OECMs. Nature 595, 646–649 (2021).

6. Morrison, T. H. et al. (2022) Radical interventions for climate-impacted systems. Nature Climate Change: 1-7.